70-1070AD World History (external support)

.

- Log in to post comments

70-1070AD "Woe to you Chorazin! Woe to you Bethsaida! Woe to you Capernaum!"

|

PROPHECY about 29 AD |

HISTORY some time within 70-1070 AD |

|

Matthew 11:20-26

Luke 10:13-16

13 Woe unto thee, Chorazin! woe unto thee, Bethsaida! for if the mighty works had been done in Tyre and Sidon, which have been done in you, they had a great while ago repented, sitting in sackcloth and ashes. 14 But it shall be more tolerable for Tyre and Sidon at the judgment, than for you. 15 And thou, Capernaum, which art exalted to heaven, shalt be thrust down to hell. 16 He that heareth you heareth me; and he that despiseth you despiseth me; and he that despiseth me despiseth him that sent me. |

Josephus commented about these places indicating they were still known locations prior to his death in the early 100's AD. Sometime following, during that first thousand years of Christendom, Chorazin, Bethsaida and Capernaum ceased to remain. Since then, historians make educated guesses as to their locations and fates. CHORAZIN BETHSAIDA CAPERNAUM |

- Log in to post comments

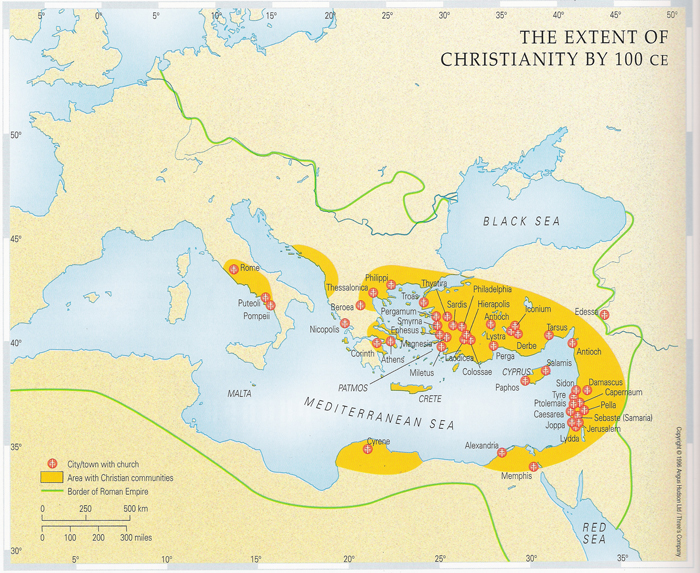

70-325AD ANTE-NICENE: the first 1/4 of the Last Day-Millennium

The first 1/4th of the Last Day-Millennium: Inheriting/Conquering the Land & Promises - answers to the Old Testament period of Joshua & Judges

- This was a period of intense conflict between the recently arrived Heavens' Empire and the outgoing Roman Empire.

- The Roman Empire recognised early on the arrival of a lethal threat to its survival and mustered every effort to defend itself against the ever-unavoidable influence of Christ's People.

- The casualty statistics of Christians killed by Romans alongside Romans surrendering to Christ can only be described as a war of super-empires.

- And within 250 years of Christ's arrival with His Saints around the time of old Jerusalem's destruction, that beast the last, saint-subjugating, idol-worshipping, superpower-empire was driven to its knees to surrender and declare itself now a Christian nation, the first. And every world superpower ever since has been one whose dominant religion is the Religion of Christ. There is neither Biblical evidence nor historical precedent that this trend will ever change.

Revelation 19:11-21

11 Now I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse. And He who sat on him was called Faithful and True, and in righteousness He judges and makes war. 12 His eyes were like a flame of fire, and on His head were many crowns. He had a name written that no one knew except Himself. 13 He was clothed with a robe dipped in blood, and His name is called The Word of God. 14 And the armies in heaven, clothed in fine linen, white and clean, followed Him on white horses. 15 Now out of His mouth goes a sharp sword, that with it He should strike the nations. And He Himself will rule them with a rod of iron. He Himself treads the winepress of the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God. 16 And He has on His robe and on His thigh a name written: KING OF KINGS AND LORD OF LORDS.

17 Then I saw an angel standing in the sun; and he cried with a loud voice, saying to all the birds that fly in the midst of heaven,"Come and gather together for the supper of the great God, 18 that you may eat the flesh of kings, the flesh of captains, the flesh of mighty men, the flesh of horses and of those who sit on them, and the flesh of all people, free and slave, both small and great."

19

And I sawthe beast, the kings of the earth, and their armies, gathered together to make war against Him who sat on the horse and against His army. 20 Then the beast was captured, and with him the false prophet who worked signs in his presence, by which he deceived those who received the mark of the beast and those who worshiped his image. These two were cast alive into the lake of fire burning with brimstone. 21 And the rest were killed with the sword which proceeded from the mouth of Him who sat on the horse. And all the birds were filled with their flesh.

NKJV

- Log in to post comments

263-339AD Eusebius: The History of the Church from Christ to Constantine

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Eusebius of Caesarea (c 263 – 339?[1]) (often called Eusebius Pamphili, "Eusebius [the friend] of Pamphilus") became the bishop of Caesarea in Palaestina c 314.[1] He is often referred to as the father of Church history because of his work in recording the history of the early Christian church, especially Chronicle and Ecclesiastical History.[1] An earlier version of church history by Hegesippus, that he referred to, has not survived.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Biography

His exact date and place of birth are unknown. However, it is estimated that he was born in 265.[2]and little is known of his youth. He became acquainted with the presbyter Dorotheus in Antioch and probably received exegetical instruction from him. In 296 he was in Palestine and saw Constantine who visited the country with Diocletian. He was in Caesarea when Agapius was bishop and became friendly with Pamphilus of Caesarea, with whom he seems to have studied the text of the Bible, with the aid of Origen's Hexapla and commentaries collected by Pamphilus, in an attempt to prepare a correct version.

In 307, Pamphilus was imprisoned, but Eusebius continued their project. The resulting defence of Origen, in which they had collaborated, was finished by Eusebius after the death of Pamphilus and sent to the martyrs in the mines of Phaeno located in modern Jordan. Eusebius then seems to have gone to Tyre and later to Egypt, where he first suffered persecution.

Eusebius is next heard of as bishop of Caesarea Maritima. He succeeded Agapius, whose time of office is not known, but Eusebius must have become bishop soon after 313. Nothing is known about the early years of his tenure. When the Council of Nicaea met in 325, Eusebius was prominent in its transactions. He was not naturally a spiritual leader or theologian, but as a very learned man and a famous author who enjoyed the special favour of the emperor, he came to the fore among the members of the council (traditionally given as 318 attendees). The confession which he proposed became the basis of the Nicene Creed.

Eusebius was involved in the further development of the Arian controversies. For instance he was involved in the dispute with Eustathius of Antioch who opposed the growing influence of Origen, including his practice of an allegorical exegesis of scripture. Eustathius perceived in Origen's theology the roots of Arianism. Eusebius was an admirer of Origen and was reproached by Eustathius for deviating from the Nicene faith - he was even alleged to hold to Sabellianism. Eustathius was accused, condemned and deposed at a synod in Antioch. Part of the population of Antioch rebelled against this action and the anti-Eustathians proposed Eusebius as its new bishop - he declined.

After Eustathius had been removed, the Eusebians proceeded against Athanasius of Alexandria, a more powerful opponent. In 334, Athanasius was summoned before a synod in Caesarea; he did not attend. In the following year, he was again summoned before a synod in Tyre at which Eusebius presided. Athanasius, foreseeing the result, went to Constantinople to bring his cause before the emperor. Constantine called the bishops to his court, among them Eusebius. Athanasius was condemned and exiled at the end of 335. At the same synod, another opponent was successfully attacked: Marcellus of Ancyra had long opposed the Eusebians and had protested against the reinstitution of Arius. He was accused of Sabellianism and deposed in 336. Constantine died the next year, and Eusebius did not long survive him. Eusebius date of death is unknown. It is estimated that he died between 337 and340 after the death of Constantine.[3]

[edit] Works

Of the extensive literary activity of Eusebius, a relatively large portion has been preserved. Although posterity suspected him of Arianism, Eusebius had made himself indispensable by his method of authorship; his comprehensive and careful excerpts from original sources saved his successors the painstaking labor of original research. Hence, much has been preserved, quoted by Eusebius, which otherwise would have been destroyed.

The literary productions of Eusebius reflect on the whole the course of his life. At first, he occupied himself with works on Biblical criticism under the influence of Pamphilus and probably of Dorotheus of Tyre of the School of Antioch. Afterward, the persecutions under Diocletian and Galerius directed his attention to the martyrs of his own time and the past, and this led him to the history of the whole Church and finally to the history of the world, which, to him, was only a preparation for ecclesiastical history.

Then followed the time of the Arian controversies, and dogmatic questions came into the foreground. Christianity at last found recognition by the State; and this brought new problems—apologies of a different sort had to be prepared. Lastly, Eusebius, the court theologian, wrote eulogies in praise of Constantine. To all this activity must be added numerous writings of a miscellaneous nature, addresses, letters, and the like, and exegetical works which include both commentaries and treatises on Biblical archaeology and extend over the whole of his life.

[edit] Biblical text criticism

Pamphilus and Eusebius occupied themselves with the text criticism of the Septuagint text of the Old Testament and especially of the New Testament. An edition of the Septuagint seems to have been already prepared by Origen, which, according to Jerome, was revised and circulated by Eusebius and Pamphilus. For an easier survey of the material of the four Evangelists, Eusebius divided his edition of the New Testament into paragraphs and provided it with a synoptical table so that it might be easier to find the pericopes that belong together. These canon tables or "Eusebian canons" remained in use throughout the Middle Ages, and illuminated manuscript versions are important for the study of early medieval art.

[edit] Chronicle

The two greatest historical works of Eusebius are his Chronicle and his Church History. The former (Greek Παντοδαπὴ Ἱστορία (Pantodape historia), "Universal History") is divided into two parts. The first part (Χρονογραφία (Chronographia), "Annals") gives an epitome of universal history from the sources, arranged according to nations. The second part (Χρονικοὶ Κανόνες (Chronikoi kanones), "Chronological Canons") furnishes a synchronism of the historical material in parallel columns, the equivalent of a parallel timeline.

The work as a whole has been lost in the original, but it may be reconstructed from later chronographists of the Byzantine school who made excerpts from the work with untiring diligence, especially George Syncellus. The tables of the second part have been completely preserved in a Latin translation by Jerome, and both parts are still extant in an Armenian translation. The loss of the Greek originals has given an Armenian translation a special importance; thus, the first part of Eusebius's "Chronicle", of which only a few fragments exist in the Greek, has been preserved entirely in Armenian. The "Chronicle" as preserved extends to the year 325. It was written before the "Church History."

[edit] Church History

In his Church History or Ecclesiastical History (Historia Ecclesiastica), Eusebius attempted according to his own declaration (I.i.1) to present the history of the Church from the apostles to his own time, with special regard to the following points:

- the successions of bishops in the principal sees;

- the history of Christian teachers;

- the history of heresies;

- the history of the Jews;

- the relations to the heathen;

- the martyrdoms.

He grouped his material according to the reigns of the emperors, presenting it as he found it in his sources. The contents are as follows:

- Book i: detailed introduction on Jesus Christ

- Book ii: The history of the apostolic time to the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus

- Book iii: The following time to Trajan

- Books iv and v: the second century

- Book vi: The time from Septimius Severus to Decius

- Book vii: extends to the outbreak of the persecution under Diocletian

- Book viii: more of this persecution

- Book ix: history to Constantine's victory over Maxentius in the West and over Maximinus in the East

- Book x: The reëstablishment of the churches and the rebellion and conquest of Licinius.

In its present form, the work was brought to a conclusion before the death of Crispus (July, 326), and, since book x is dedicated to Paulinus of Tyre who died before 325, at the end of 323, or in 324. This work required the most comprehensive preparatory studies, and it must have occupied him for years. His collection of martyrdoms of the older period may have been one of these preparatory studies.

Eusebius blames the calamities which befell the Jewish nation on the Jews' role in the death of Jesus. This quote has been used to attack both Jews and Christians. See Christianity and anti-Semitism.

- "that from that time seditions and wars and mischievous plots followed each other in quick succession, and never ceased in the city and in all Judea until finally the siege of Vespasian overwhelmed them. Thus the divine vengeance overtook the Jews for the crimes which they dared to commit against Christ." (Hist. Eccles. II.6: The Misfortunes which overwhelmed the Jews after their Presumption against Christ) [1]

This is not simply anti-semitism, however. Eusebius levels a similar charge against Christians, blaming a spirit of divisiveness for some of the most severe persecutions.

- "But when on account of the abundant freedom, we fell into laxity and sloth, and envied and reviled each other, and were almost, as it were, taking up arms against one another, rulers assailing rulers with words like spears, and people forming parties against people, and monstrous hypocrisy and dissimulation rising to the greatest height of wickedness, the divine judgment with forbearance, as is its pleasure, while the multitudes yet continued to assemble, gently and moderately harassed the episcopacy. (Hist. Eccles. VIII.1: The Events which preceded the Persecution in our Times.) [2]

[edit] Life of Constantine

Eusebius' Life of Constantine (Vita Constantini) is a eulogy or panegyric, and therefore its style and selection of facts are affected by its purpose, rendering it inadequate as a continuation of the Church History. As the historian Socrates Scholasticus said, at the opening of his history that was designed as a continuation of Eusebius, "Also in writing the life of Constantine, this same author has but slightly treated of matters regarding Arius, being more intent on the rhetorical finish of his composition and the praises of the emperor, than on an accurate statement of facts." The work was unfinished at Eusebius' death.

[edit] Minor historical works

Before he compiled his church history, Eusebius edited a collection of martyrdoms of the earlier period and a biography of Pamphilus. The martyrology has not survived as a whole, but it has been preserved almost completely in parts. It contained:

- an epistle of the congregation of Smyrna concerning the martyrdom of Polycarp;

- the martyrdom of Pionius;

- the martyrdoms of Carpus, Papylus, and Agathonike;

- the martyrdoms in the congregations of Vienne and Lyon;

- the martyrdom of Apollonius.

Of the life of Pamphilus, only a fragment survives. A work on the martyrs of Palestine in the time of Diocletian was composed after 311; numerous fragments are scattered in legendaries which still have to be collected. The life of Constantine was compiled after the death of the emperor and the election of his sons as Augusti (337). It is more a rhetorical eulogy on the emperor than a history but is of great value on account of numerous documents incorporated in it.

[edit] Apologetic and dogmatic works

To the class of apologetic and dogmatic works belong:

- the Apology for Origen, the first five books of which, according to the definite statement of Photius, were written by Pamphilus in prison, with the assistance of Eusebius. Eusebius added the sixth book after the death of Pamphilus. We possess only a Latin translation of the first book, made by Rufinus;

- a treatise against Hierocles (a Roman governor and Neoplatonic philosopher), in which Eusebius combated the former's glorification of Apollonius of Tyana in a work entitled "A Truth-loving Discourse" (Greek, Philalethes logos);

- Praeparatio evangelica ('Preparation for the Gospel'), commonly known by its Latin title, which attempts to prove the excellence of Christianity over every pagan religion and philosophy. The Praeparatio consists of fifteen books which have been completely preserved. Eusebius considered it an introduction to Christianity for pagans. But its value for many later readers is more because Eusebius studded this work with so many fascinating and lively fragments from historians and philosophers which are nowhere else preserved. Here alone is preserved a summary of the writings of the Phoenician priest Sanchuniathon of which the accuracy has been shown by the mythological accounts found on the Ugaritic tables, here alone is the account from Diodorus Siculus's sixth book of Euhemerus' wondrous voyage to the island of Panchaea where Euhemerus purports to have found his true history of the gods, and here almost alone is preserved writings of the neo-Platonist philosopher Atticus along with so much else.

- Demonstratio evangelica ('Proof of the Gospel') is closely connected to the Praeparatio and comprised originally twenty books of which ten have been completely preserved as well as a fragment of the fifteenth. Here Eusebius treats of the person of Jesus Christ. The work was probably finished before 311;

- another work which originated in the time of the persecution, entitled "Prophetic Extracts" (Eklogai prophetikai). It discusses in four books the Messianic texts of Scripture. The work is merely the surviving portion (books 6-9) of the General elementary introduction to the Christian faith, now lost.

- the treatise "On Divine Manifestation" (Peri theophaneias), dating from a much later time. It treats of the incarnation of the Divine Logos, and its contents are in many cases identical with the Demonstratio evangelica. Only fragments are preserved in Greek, but a complete Syriac translation of the Theophania survives in an early 5th century manuscript.

- the polemical treatise "Against Marcellus," dating from about 337;

- a supplement to the last-named work, entitled "On the Theology of the Church," in which he defended the Nicene doctrine of the Logos against the party of Athanasius.

A number of writings, belonging in this category, have been entirely lost.

[edit] Exegetical and miscellaneous works

Of the exegetical works of Eusebius, nothing has been preserved in its original form. The so-called commentaries are based upon late manuscripts copied from fragments of catenae. A more comprehensive work of an exegetical nature, preserved only in fragments, is entitled "On the Differences of the Gospels" and was written for the purpose of harmonizing the contradictions in the reports of the different Evangelists. While this latter work existed in the 16th century, it has since been lost apart from an epitome. It was also for exegetical purposes that Eusebius wrote his treatises on Biblical archeology:

- a work on the Greek equivalents of Hebrew Gentilic nouns;

- a description of old Judea with an account of the loss of the ten tribes;

- a plan of Jerusalem and the Temple of Solomon.

These three treatises have been lost. A work known as the Onomasticon, entitled in the main Greek manuscript "Concerning the Place-names in Sacred Scripture",[4] is still in existence. This is an alphabetical dictionary of Biblical place names, often including identifications with places existing in Eusebius' own time. Further mention is to be made of addresses and sermons some of which have been preserved, e.g., a sermon on the consecration of the church in Tyre and an address on the thirtieth anniversary of the reign of Constantine (336). Of the letters of Eusebius only a few fragments are extant.

[edit] Estimate of Eusebius

[edit] Doctrine

From a dogmatic point of view, Eusebius stands entirely upon the shoulders of Origen and Arius. Like Origen, he started from the fundamental thought of the absolute sovereignty (monarchia) of God. God is the cause of all beings. But he is not merely a cause; in him everything good is included, from him all life originates, and he is the source of all virtue. God sent Christ into the world that it may partake of the blessings included in the essence of God. Christ is God and is a ray of the eternal light; but the figure of the ray is so limited by Eusebius that he expressly emphasizes the self-existence of Jesus.

Eusebius was intent upon emphasizing the difference of the persona of the Trinity and maintaining the subordination of the Son (Logos, or Word) to God (he never calls him theos) because in all contrary attempts he suspected polytheism or Sabellianism. The Son (Jesus), as Arianism asserted, is a creature of God whose generation, for Eusebius, took place before time. Jesus acts as the organ or instrument of God, the creator of life, the principle of every revelation of God, who in his absoluteness and transcendent is enthroned above and isolated from all the world. This Logos, as a derivative creature and not truly God as the Father is truly God, could therefore change (Eusebius, with most early theologians, assumed God was immutable), and he assumed a human body without altering the immutable divine Father. The relation of the Holy Spirit within the Trinity Eusebius explained similarly to that of the Son to the Father. No point of this doctrine is original with Eusebius, all is traceable to his teachers Arius and Origen. The lack of originality in his thinking shows itself in the fact that he never presented his thoughts in a system. After nearly being excommunicated for his heresy by Alexander of Alexandria, Eusebius submitted and agreed to the Nicene Creed at the First Council of Nicaea.

[edit] Limitations

Eusebius is often regarded as the first court appointed Christian theologian in the service of the Constantine Roman Empire, seeing the Empire and the Imperial Church as closely bonded.[3] Notwithstanding the great influence of his works on others, Eusebius was not himself a great historian. [4] His treatment of heresy, for example, is inadequate, and he knew very little about the Western church. His historical works are really apologetics. In his Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 8, chapter 2, he points out, "We shall introduce into this history in general only those events which may be useful first to ourselves and afterwards to posterity."

In his Praeparatio evangelica (xii, 31), Eusebius has a section on the use of fictions (pseudos) as a "medicine", which may be "lawful and fitting" to use [5]. With that in mind, it is still difficult to assess Eusebius' conclusions and veracity by confronting him with his predecessors and contemporaries, for texts of previous chroniclers, notably Papias, whom he denigrated, and Hegesippus, on whom he relied, have disappeared; they survive largely in the form of the quotes of their work that Eusebius selected and thus they are to be seen only through the lens of Eusebius.

These and other issues have invited controversy. For example, Jacob Burckhardt has dismissed Eusebus as "the first thoroughly dishonest historian of antiquity". and was not alone in holding such a view. He has also been accused of dishonesty at various times, and in various connections by other historians:

- Gibbon dismissed his testimony on the number of martyrs and impugned his honesty by referring to two passages. The first occurs in the Ecclesiastical History, book 8, chapter 2, in which Eusebius introduces his discussion of the Great Persecution under Diocletian with: "Wherefore we have decided to relate nothing concerning them except the things in which we can vindicate the Divine judgment. [...] We shall introduce into this history in general only those events which may be useful first to ourselves and afterwards to posterity.". And the second, in the Martyrs of Palestine, chapter 12, in which Eusebius makes a long list of events which he says he omits from his text: "I think it best to pass by all the other events which occurred in the meantime: such as [...] the lust of power on the part of many, the disorderly and unlawful ordinations, and the schisms among the confessors themselves; also the novelties which were zealously devised against the remnants of the Church by the new and factious members, who added innovation after innovation and forced them in unsparingly among the calamities of the persecution, heaping misfortune upon misfortune. I judge it more suitable to shun and avoid the account of these things, as I said at the beginning."[5]

- Gibbon also pointed out that the chapter heading in Eusebius' Praeparatio evangelica (xii, 31), says how fictions (pseudos) — which Gibbon rendered 'falsehoods' — may be a "medicine", which may be "lawful and fitting" to use [6]. But the text is discussing parallels between the Bible and the theories of Plato on education, and Eusebius is suggesting that the Bible also contains such material. Unless it is supposed that Eusebius believes the Bible to be deceptive, it is easy to see why Gibbon confined his remark to the chapter heading (which may not be authorial anyway), and why Gibbon was accused of dishonesty in his attacks on Eusebius.[6] However, it can also be argued that Eusebius would logically have the same thinking when it came to politics, if this was his opinion about mere interpretations of the Bible.

- Questions were long raised by scholars[attribution needed] about whether all the documents in the Life of Constantine were authentic.[citation needed]

But other views have tended to prevail.

- Joseph Lightfoot rebutted the arguments of Gibbon[7], pointing out that Eusebius' very frank statements indicate his honesty in stating what he was not going to discuss, and also his limitations as a historian in not including such material. He also discusses the question of accuracy. "The manner in which Eusebius deals with his very numerous quotations elsewhere, where we can test his honesty, is a sufficient vindication against this unjust charge." But he accepts that Eusebius cannot always be relied on. "A far more serious drawback to his value as a historian is the loose and uncritical spirit in which he sometimes deals with his materials. This shews itself in diverse ways. (a) He is not always to be trusted in his discrimination of genuine and spurious documents."

- G. A. Williamson has written, "Gibbon's notorious sneer ... was effectively disposed of by Lightfoot, who fully vindicated Eusebius' honour as a narrator 'against this unjust charge'."[7]

- Averil Cameron and Stuart Hall, in their recent translation of the Life of Constantine point out that writers such as Burckhardt found it necessary to attack Eusebius in order to undermine the ideological legitimacy of the Hapsburg empire, which based itself on the idea of Christian empire derived from Constantine, and that the most controversial letter in the Life has since been found among the papyri of Egypt.[8]

- Michael J. Hollerich, replying to Burckhardt's criticism of Eusebius, thinks that criticisms goes too far. Writing in "Church History" (Vol. 59, 1990), he says that ever since Burckhardt, "Eusebius has been an inviting target for students of the Constantinian era. At one time or another they have characterized him as a political propagandist, a good courtier, the shrewd and worldly adviser of the Emperor Constantine, the great publicist of the first Christian emperor, the first in a long succession of ecclesiastical politicians, the herald of Byzantinism, a political theologian, a political metaphysician, and a caesaropapist. It is obvious that these are not, in the main, neutral descriptions. Much traditional scholarship, sometimes with barely suppressed disdain, has regarded Eusebius as one who risked his orthodoxy and perhaps his character because of his zeal for the Constantinian establishment." He concludes that "the standard assessment has exaggerated the importance of political themes and political motives in Eusebius's life and writings and has failed to do justice to him as a churchman and a scholar".

While many have shared Burckhardt's assessment, particularly with reference to the Life of Constantine, others, while not pretending to extol his merits, have acknowledged the irreplaceable value of his works. The value of his works has generally been sought in the copious quotations that they contain from other sources, often lost.

[edit] See also

| Preceded by Agapius | Bishop of Caesarea ca. 313-339/340 | Succeeded by Acacius |

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b c Wetterau, Bruce. World history. New York: Henry Holt and company. 1994.

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Early Church, Published in 1992, English Version, page 299

- ^ The Essential Eusebius page 31. Published by Mentor-Omega Book in New yYork and Toronto. Year of publication 1966

- ^ C. Umhau Wolf [1971] (2006). The Onomasticon of Eusebius Pamphili Compared with the Version of Jerome and Annotated. The Tertullian Project, p. xx. Retrieved on 2007-12-08.

- ^ Edward Gibbon, Decline and Fall, vol. 1, chapter 16

- ^ See Gibbon's Vindication for examples of the accusations that he faced.

- ^ G. A. Williamson, Eusebius of Caesarea: Church History Penguin Books, 1965, introduction.

- ^ Averil Cameron, Stuart G. Hall, Eusebius' Life of Constantine. Introduction, translation and commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Pp. xvii + 395. ISBN 0-19-814924-7. Reviewed in BMCR

[edit] References

- "Eusebius Of Caesarea." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2005. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. 4 December 2005. Reference cited for statement that Eusebius was not a great historian.

- Initial text from Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religion, subjected to edits for style.

[edit] External links

[edit] Online works

- Historia Ecclesiastica at the CCEL (English translation for the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers)

- Vita Constantini at the CCEL (English translation for the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers)

- Contra Hieroclem at the Tertullian Project (English translation)

- Demonstratio Evangelica at the Tertullian Project (English translation)

- Encomium of the Martyrs at the Tertullian Project (English translation from an ancient Syriac version)

- History of the Martyrs in Palestine at the Tertullian Project (English translation from an ancient Syriac version)

- Onomasticon at the Tertullian Project (English translation)

- Praeparatio Evangelica at the Tertullian Project (English translation)

- Theophania at the Tertullian Project (English translation from an ancient Syriac version)

- To Carpianus at the Tertullian Project (English translation)

- Letters at the Patristics In English Project (English Translation From Various Sources)

- "Article on Eusebius in the New Advent Catholic Encylopeida"

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Graeca with analytical indexes

[edit] Other links

- Eusebius of Caesarea at the Tertullian Project

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Eusebius of Caesarea

- A discussion of the questionable scholarship of the early Christian historians - at Infidels.org

- EarlyChurch.org.uk Extensive bibliography.

- Analysis: Writings on Oration of Constantine

- Textual, chronological, and bibliographical information on his works from Fourth Century Christianity

- Log in to post comments

272-337AD Roman Emperor Constantine: the first Christian world leader

From: http://preteristarchive.com/Theo-Political_Empire/Roman/StudyArchive/constantine_preterist.html

Constantine the.. Preterist!

"This remarkable event (the Edict of Milan) was regarded by Christians of that time, and by Constantine himself, as the fulfillment of the very prophecy before us. (Revelation 20:2)" |

Eusebius Pamphilius: Oration in Praise of Constantine "I am filled with wonder at the intellectual greatness of the emperor, who as if by divine inspiration thus expressed what the prophets had foretold concerning this monster"

First Christian ruler of the Roman Empire

Constantine I came to the throne when his father, Constantius, died in 306. After defeating his rivals, Constantine became the sole ruler of the Roman Empire in 324, and is credited with social and economic reforms that significantly influenced medieval society. In 313 his Edict of Milan legally ended pagan persecution of Christians, and in 325 he used imperial power to bring unity to the church at the Council of Nicea. He also moved the capital of his empire to Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople in 330. Constantine's embrace of Christianity eventually led him to be baptized in 337. |

Eusebius Pamphilius

"Chapter III.--Of his Picture surmounted by a Cross and having beneath it a Dragon.

And besides this, he caused to be painted on a lofty tablet, and set up in the front of the portico of his palace, so as to be visible to all, a representation of the salutary sign placed above his head, and below it that hateful and savage adversary of mankind, who by means of the tyranny of the ungodly had wasted the Church of God, falling headlong, under the form of a dragon, to the abyss of destruction. For the sacred oracles in the books of God's prophets have described him as a dragon and a crooked serpent; [Especially the book of Revelation, and Isaiah] and for this reason the emperor thus publicly displayed a painted resemblance of the dragon beneath his own and his children's feet, stricken through with a dart, and cast headlong into the depths of the sea.

In this manner he intended to represent the secret adversary of the human race, and to indicate that he was consigned to the gulf of perdition by virtue of the salutary trophy placed above his head. This allegory, then, was thus conveyed by means of the colors of a picture: and I am filled with wonder at the intellectual greatness of the emperor, who as if by divine inspiration thus expressed what the prophets had foretold concerning this monster, saying that "God would bring his great and strong and terrible sword against the dragon, the flying serpent; and would destroy the dragon that was in the sea." [Isa. xxvii.] This it was of which the emperor gave a true and faithful representation in the picture above described." (Oration in Praise of Constantine)

Isaiah 27:1

"In that day the LORD with his sore and great and strong sword shall punish leviathan the piercing serpent, even leviathan that crooked serpent; and he shall slay the dragon that is in the sea."Revelation 12:3

And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads. 4 And his tail drew the third part of the stars of heaven, and did cast them to the earth: and the dragon stood before the woman which was ready to be delivered, for to devour her child as soon as it was born. 5 And she brought forth a man child, who was to rule all nations with a rod of iron: and her child was caught up unto God, and to his throne. 6 And the woman fled into the wilderness, where she hath a place prepared of God, that they should feed her there a thousand two hundred and threescore days. 7 And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, 8 And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven. 9 And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him. 10 And I heard a loud voice saying in heaven, Now is come salvation, and strength, and the kingdom of our God, and the power of his Christ: for the accuser of our brethren is cast down, which accused them before our God day and night. 11 And they overcame him by the blood of the Lamb, and by the word of their testimony; and they loved not their lives unto the death. 12 Therefore rejoice, ye heavens, and ye that dwell in them. Woe to the inhabiters of the earth and of the sea! for the devil is come down unto you, having great wrath, because he knoweth that he hath but a short time. 13 And when the dragon saw that he was cast unto the earth, he persecuted the woman which brought forth the man child. 14 And to the woman were given two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly into the wilderness, into her place, where she is nourished for a time, and times, and half a time, from the face of the serpent. 15 And the serpent cast out of his mouth water as a flood after the woman, that he might cause her to be carried away of the flood. 16 And the earth helped the woman, and the earth opened her mouth, and swallowed up the flood which the dragon cast out of his mouth.Revelation 13

2 And the beast which I saw was like unto a leopard, and his feet were as the feet of a bear, and his mouth as the mouth of a lion: and the dragon gave him his power, and his seat, and great authority. 4 And they worshipped the dragon which gave power unto the beast: and they worshipped the beast, saying, Who is like unto the beast? who is able to make war with him?Revelation 20:2

And he laid hold on the dragon, that old serpent, which is the Devil, and Satan, and bound him a thousand years,

Jonathan Edwards

"This revolution was the greatest revolution and change in the face of things that ever came to pass in the world since the flood. Satan, the prince of darkness, that king and god of the heathen world, was cast out. The roaring lion was conquered by the Lamb of God in the strongest dominion that ever he had, even the Roman Empire." (Work of Redemption, Period 3, Section 2)

William S. Urmy in "Christ Came Again"

Israel P. Warren in "The Parousia"

CHRISTIAN COINAGE

UNDER

CONSTANTINE

Numismatic Chronicle - Constantine (1877 PDF)

"The type of these pieces and the inscription indicate how the "public hope" was centered in the triumph of the Christian religion over the adversary of mankind -- "the great dragon, that old serpent called the Devil and Satan" (Rev. xii. 9 ; xx. 2), and Eusebius tells us how Constantine I had a picture painted of the dragon -- the flying serpent -- beneath his own and his children's feet, pierced through the middle with a dart, and cast into the depths of the sea."

Old coins and their contribution. Considerable disparity exists among historians about the time of Constantine’s conversion to Christianity and about the details of his momentous vision. There is also debate as to whether history can be deduced from the study of old coins or numismatics in general. It appears that in all three cases, the ultimate judgment must rest with each student, depending upon the degree of penetration and the quality of study applied. Verifiable facts -- the external evidence -- do not always explain the meaning of historical events or their internal significance. The interpretation of history is often a subjective involvement, as historians tend to provide their own understanding and interpretations.

An exemplary case of historical interpretation based on ancient coinage and existing literature is the following essay by the distinguished Constantinian Knight Commander, Craig Peter Barclay, M.A., M.Litt. The author has served as Keeper of Numismatics at the Yorkshire Museum in York, U.K. and has previously held curatorial positions at the Royal Mint and University of Aberdeen.

______________________

Hoc Signo Victor Eris: By

Craig Barclay

In a world without newspapers and television, the circulating coinage provided a potent means for ruling authorities to disseminate political and religious propaganda. Few such authorities have been more conscious of the potential value of this medium than the Roman emperors, and it can be argued that none of those made more effective use of it than Constantine the Great.

As the first emperor to embrace the Christian faith, we might expect that Constantine’s religious convictions would figure prominently on the coinage of his reign. The degree to which this was actually the case has provoked great deal of scholarly argument and, in so doing, has provided a number of fascinating insights into the development of religious symbolism in the fledgling Christian Empire.

General

As Andrew Alfoldi has rightly observed (p. 41), ‘The coin types of the period are, in every case, mere feeble copies of those great works of art that have not come down to us.’ Nevertheless, he would contend, they have also provided us with ‘absolute proof that the Emperor embraced the Christian cause with a suddenness that surprised all but his most intimate colleagues.’ (Alfoldi, pp. 1-2)

(Fig. 1) Constantine the Great; bronze follis; AD 337-40

A more recent scholar, Andrew Burnett, however argues that representations of pagan gods only disappear from Constantine’s coinage after AD 318 and, even then, the designs that replaced them were primarily religiously neutral in content. ‘The only explicitly Christian coin designs were the representations of the emperor in an attitude of prayer, and a very rare design used by the mint of Constantinople in about 327, showing a banner with a chi-rho monogram spearing a serpent, representing his enemy Licinius.’ (Burnett, p. 145)

Clearly the nature and significance of the designs used by Constantine on his coinage are open to more than one interpretation. We must accordingly address the complex question: ‘Can we see the Christian faith of Constantine the Great reflected in his coinage?’

Sol Invictus

Flavius Valerius Constantinus was born in about AD 285 at Naissus in Serbia, the son of the Tetrarch Constantius I and his wife, the Empress Helena. After spending his early years as an effective hostage at the courts of Diocletian and his successor Galerius, Constantine escaped to the west, joining his father in York shortly before the latter’s death on 25 July AD 306. Proclaimed emperor by the army at York, Constantine spent the next eighteen years disposing of his rivals for control of the empire through an elaborate series of shifting political alliances and military campaigns.

During the early part of his reign representations of first Mars and then, from AD 310, Apollo-Sol dominated Constantine’s coinage. Mars had been intimately associated with the Tetrarchy, and Constantine’s use of this symbolism served to emphasise the legitimacy of his rule. After his breach with his father’s old colleague Maximian in AD 309-10, Constantine began to claim legitimate descent from the third-century emperor Claudius Gothicus. Gothicus had claimed the divine protection of the Apollo-Sol . As Burnett notes (pp. 143-44), in AD 310 Constantine experienced a vision in which Apollo-Sol appeared to him with omens of success. ‘Thereafter his coinage was dominated for several years by "his companion the unconquered Sol", SOLI INVICTO COMITI.’

(Fig. 2) Constantine the Great; bronze follis; AD 316-17

(Fig. 2) Constantine the Great; bronze follis; AD 316-17

According to Lactantius, just prior to the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in AD 312, Constantine experienced a dream-vision urging him to trust the fate of his army to the Christian God, and to place the symbol of the monogrammatic cross on the shields of his army. In his Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius’s account of Constantine’s vision differs slightly, claiming that Constantine experienced a vision at the beginning of his military campaign wherein the symbol of the cross appeared on the face of the sun, accompanied by the Greek words, ‘In this sign conquer’. Subsequently, Eusebius tells us, Constantine experienced a second vision, in which he was urged to use the Christian sign to protect himself from his foes. In response to this latter vision, Constantine had a labarum or standard produced, bearing the name of Christ in the form of a monogram of the Greek letters X and P (the Chi-Rho).

Whatever the detail, Constantine duly placed his trust in the Cross and duly defeated his imperial rival, Maxentius, on the outskirts of Rome itself. Nevertheless, in the wake of this great victory, no immediate change took place in the basic design of the coinage, with issues celebrating Sol Invictus continuing to form the bulk of the circulating medium. Indeed, as Vermeule (p. 180) explains, even in AD 313, on the very eve of the Edict of Toleration, Constantine was still portrayed on huge gold medallions in the company of Sol Invictus and bearing a shield decorated with a representation he sun-god’s chariot.

Nevertheless, after the final defeat of Licinius, the pagan gods disappeared from the coinage of Constantine, their place being taken by religiously neutral images. The question might be asked as to why Constantine did at last begin to make extensive use of specifically Christian images at this time but, as Runciman (p. 17) bluntly reminds us, ‘The earliest Christians took little interest in art.’

Accordingly, during the early 4th century AD, there were few artistic motifs available that could be relied upon to convey a specifically Christian message. Even the Chi-Rho, which is today universally recognised as a Christian sign, could be misinterpreted, Bruun (p. 61) reminding us that, ‘The sign, at the moment of its creation, was ambiguous. In essence it was a monogram composed of the Greek letters X and P, and, while the monogrammatic combination of these two letters was by no means unusual in pre-Constantinian times, the occurrence of X P with a clearly Christian significance is exceedingly rare.’ The potential significance of the sign would initially have been lost on the non Greek-speaking population of the empire, who might more readily have interpreted the sign as being linked to Solar or Mithraic worship.

Such initial ambiguities notwithstanding, there can be no doubt that Constantine saw his victorious sign as being an explicitly Christian symbol nor that, in the wake of the writings of Eusebius and Lactantius, its religious meaning came rapidly to be universally recognised. Constantine made only sparing use of the Chi-Rho on his coins, confining its use to a few scarce issues only. Following his death however, this most powerful symbol came to be used increasingly frequently, both as a means of celebrating the religious convictions of the succeeding emperors, and as a means of affirming the legitimacy of their succession from Constantine.

(Fig. 3) Eudoxia; gold solidus; AD 397-402

Although also adopted by Constantine’s sons, the most prominent early use of the Chi-Rho occurred during the reign of the usurper Magnentius (AD 350-53), who struck large bronze double centenionales decorated with a large Christogram flanked by the Greek letters alpha and omega. Thereafter the symbol appeared time after time on the coinages of both the western and eastern empires, its position as the primary symbol of the new state religion only gradually being superseded by the plain, unadorned Cross.

Constantinus Orans

As the image of the emperor most commonly seen by the public, the portrait of the emperor reproduced on the imperial coinage was considered to be of the utmost importance. Constantine’s coinage portraits break away from the traditions of the previous two centuries, calling upon both earlier Imperial and Greek precedents for inspiration. The Imperial beard, which had been sported by almost all emperors since the beginning of the second century, was abandoned and replaced by a clean shaven image. Likewise, the laurel wreath or solar crown which had dominated the coinages of the second and third centuries were dropped in favour of an eastern diadem, or, less frequently, a military helmet.

(Fig. 4) Constantine the Great; gold solidus; AD 326

One particular version of the new imperial image has attracted particular attention. Eusebius (4.15) was quite explicit in his statement that Constantine was portrayed on his coinage in an attitude of prayer: ‘He directed his likeness to be stamped on a gold coin with his eyes uplifted in the posture of prayer to God … this coin was current through the Roman world and was a sign of the power of divine faith.’ Burnett recognises this passage as important evidence implying ‘that important members of the higher social classes noticed coin designs’, adding that ‘There can hardly be any doubt that Eusebius had seen the coins in question’.

(Fig. 5) Constantine the Great; gold solidus; AD 326-27

Not all authors have accepted these coins as representing the emperor’s devotion to the Christian faith and, as L’Orange has pointed out (1947, p.34), the ‘heaven-gazing’ coin portraits of Constantine have been the subject of numerous interpretations, including an argument that it should be interpreted as a representation of the Sol-emperor Constantine fixing his gaze upon the goddess Luna. L’Orange (1947, p.94) would consequently argue that, ‘Constantine as Christian orant is, therefore, an arbitrary interpretation of his heavenward-looking portrait. This does not however alter the fact that the type became for Christians, perhaps owing to the very weight of Eusebius’ authority, an expression of Constantine’s inspired relation to their own God, a representation of the Christ-emperor.’

This argument has in part been fuelled by the undoubted fact that the so-called Constantinus orans portrait type is ultimately derived from pagan prototypes first seen during the reign of the Hellenic monarch Alexander the Great (Toynbee, p. 148). Bruun (p. 33), who does not accept that the coin type bears any specific Christian significance, nevertheless concedes that the heavenward-gazing portraits of Constantine recall ‘portraits of the Hellenistic ruler, whose heavenward look expresses the inner contact between the emperor and the heavenly powers.’

Most however have been more than content to recognise the Christian spirituality of these most beautiful images. The heavenward-gazing portrait is not peculiar to the coinage and Alfoldi (p. 34) recalls that ‘Apart from the monogram of salvation, the statues, paintings, and coin-types displayed, throughout the Empire, the gaze of the "most religious Majesty", directed heavenward’. The same point has been effectively argued by L’Orange (1965, pp. 123-24), who noted in writing of a colossal head of Constantine from the Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome that ‘The eyes, being supernaturally large and wide-open and framed by the accentuated concentric curves of the deepcut lids and brows, express more clearly than ever the transcendence of the ruler’s personality. In this gaze he travels far beyond his physical surroundings and attains his goal in a higher sphere, in contact and identity with the governing powers. Providence in person, the irresistible controller of fate, fatorum arbiter, rises before us, with all the future on his knees.’

Yet another distinguished scholar likewise observes that, ‘Long before his formal conversion to Christianity Constantine had associated himself with purely Christian policy, and his finer portrait show the upward-tilted head of the man with his mind on the heavens, or the facing head, dazzling within its halo, of the world’s half-Christian master.’ (Sutherland, p. 103). Irrespective of the pagan origins of the orant portrait it had, through its adoption by Constantine, come to express a wholly new significance. ‘The outward forms of expression remain very much as before … But the inner meaning has completely changed. The pagan Emperor was never clearly distinguished in nature from the deity whose vice-regent he was: hence the divine attributes and all his pomp and state. The maiestas of the Christian Emperor, the "vicarius Dei", is wholly derivative: between him and his God there is a fixed and impassable gulf, that between the creature and his Creator, which God-given Grace alone can bridge.’ (Toynbee, p. 149)

It is significant that the orant portrait was used not only on coins of Constantine himself, but also on coins struck during his reign in the names of is appointed successors (L’Orange 1947, p. 91). After his death in AD 337 however, Constantine’s sons made only very limited use of the highly distinctive portrait, perhaps regarding it as being a reflection of their father’s personal relationship with his God.

If the orant portrait did not long survive the death of Constantine, other stylistic elements of his coin portraits did. From this point onwards the imperial image reproduced on the coinage ceased to attempt accurately to reproduce the actual features of the living monarch. Instead the portraits became mere ciphers, representing a stylised rather than personal image of imperial majesty. All of these images nevertheless borrowed heavily from Constantinian prototypes adopting, for example, the eastern diadem and clean-shaven features of the first Christian emperor. Indeed, the clean shaven portrait came so closely to be associated with the new faith that when the pagan emperor Julian the Apostate (AD 360-63) briefly gained the throne, he swiftly adopted a bearded portrait in order to disassociate himself from his Christian predecessors. With Julian’s death, shaven portraits once again became the norm, remaining so until long after the fall of Rome.

Helmet

Alfoldi (p. 27), in arguing that Constantine’s religious policy was not based on ‘conscious ambiguity’, states that the appearance of the Chi-Rho on Constantine’s helmet ‘on issues of coins from all quarters, soon after the defeat of Maxentius, loudly and unmistakably claimed where Constantine stood.’ He further asserts that, ‘We can prove beyond a doubt, by the evidence of coin types appearing soon after, that Constantine caused the monogram of Christ to be inscribed on his helmet before the decisive battle with Maxentius’. (Alfoldi, p. 17)

Alfoldi (pp. 39-40) further states, in defence of the significance of the Chi-Rho that, ‘Eusebius knows that Constantine not only bore the Christian symbol on his helmet in the fight against Maxentius, but continued to wear it in his golden, bejewelled helmet of state. When … the representation of this helmet, that was new in its pattern, soon appears on the coins, we cannot possibly regard it as a mere sign of zeal on the part of Christian subordinates. The tiniest detail of the imperial dress was the subject of a symbolism that defined rank, that was hallowed by tradition and regulated by precise rules. Anyone who irresponsibly tampered with it would have incurred the severest penalties. Especially would this have been the case if anyone, without imperial authority, had provided the head-gear of the Emperor with a sign of such serious political importance as that attached to the monogram of Christ’.

A very similar position has been adopted by Voght (p. 90), who explains that, ‘we have other witnesses to the piety of the new ruler of Rome and from these we learn that Constantine gave public expression to his gratitude to his divine patron. The magnificent silver medallion, whose obverse and reverse depict the conquest and liberation of the city, was probably struck at the mint of Ticinum (near modern Milan) as early as 313: and on the obverse the monogram appears, on the crested plume of Constantine’s helmet. In a prestige issue of this type, the incorporation of the Christ-monogram into the portrait of the emperor could only have been done on the highest authority.’

Burnett (p. 146) similarly draws attention to the same silver medallion (actually struck at Rome or Aquileia in AD 315) and a series of small bronze coins struck at Siscia in c. AD 320. On all of these, the emperor is clearly portrayed with the Chi-Rho symbol prominently displayed on his helmet. ‘It is indeed hard to disassociate them from Eusebius’s explicit statement that Constantine placed the Chi-Rho on his helmet, but the very occasional nature of its appearance on coins should make us cautious about making too much of this. On coins issued in about 322 at Trier, for instance, the chi-rho appears as the decoration on the shield held by Constantine’s son Crispus; but it happened on only one die and must represent the personal choice of a die engraver, as the other shields for the same group of coins have different sorts of decoration on the shields.’

Even Bruun (p. 63), who is dismissive of the appearance of the Christogram on some Victoriae laetae princ perp coins of Siscia (describing them as ‘engraver’s slips’), accepts the symbolic significance of the use of the same symbol on the silver medallions of AD 315, writing that, ‘The silver multiples with their facing portraits represent an altogether different case. The Chi-Rho is here set in a badge just below the root of the crest. The official character of the badge has recently been demonstrated in a convincing manner. No doubt, therefore, persists about the meaning of the new emblem: the emperor has adopted his own victorious sign as a symbol of power.’

Labarum

The mint of Constantinople was in operation by AD 327, some three years before the formal dedication of the city. A series of bronze coins of that year celebrate the defeat of Licinius. The reverse of this issue bears the legend Spes Publica, and portrays a serpent being pierced by a Chi-Rho topped labarum.

For Alfoldi (p. 39), ‘The spectacle of the Christian monogram on works of art and coin-types, the blaze of the initials of Christ on the labarum, the new imperial banner, were all propaganda in the modern sense’. Even Bruun (p. 64), whilst generally dismissive of the existence of Christian symbols on the coinage of Constantine, is forced to concede that ‘The problem of the labarum piercing the dragon on the Constantinopolitan Spes publica bronzes remains.’

Whilst rarely used during Constantine’s reign, the Christian labarum becomes a frequent and recurrent feature of the coinage following his death, normally being closely associated with a representation of a victorious emperor. One particular issue, struck at Siscia in AD 350, makes specific reference to Constantine’s vision, bearing the labarum accompanied by the legend Hoc Signo Victor Eris - ‘In this sign shalt thou conquer’.

(Fig. 6) Constantius II; bronze coin of Siscia; AD 350

Mintmarks

During the Roman period coins were struck at a large number of mints situated throughout the empire. As a quality-control mechanism, the coins struck by each of these mints were required to bear distinctive mintmarks, identifying their place of manufacture. The decision to use the Chi-Rho or other apparently Christian symbols as mintmarks on some of Constantine’s coins is dismissed by Bruun (p. 62) as being the responsibility of procurators or, in one case, the rationalis summarum. Approval to use these symbols was given ‘very far from the emperor and court and comes sacrarum largitionum.’

Burnett (pp. 145-46) likewise acknowledges that the Chi-Rho appears on a number of issues of coins ‘as one of the stock symbols used for mint-marks’, but - like Bruun - argues that its use is more likely to reflect the rise of Christian administrators to positions of authority in Constantine’s regime rather than an official policy decision. Even if not centrally authorised, the first use of Christian mintmarks can accordingly be seen to be of the greatest significance, illustrating as it does the shift in the status of Christians within the machinery of the Roman state. Not surprisingly, in the years that followed, the choice of both the Chi-Rho and the plain Cross came increasingly to form a key element of the privy marks adopted by the empire’s numerous mints.

Cross-sceptre

On 17 May AD 330 Constantine dedicated his new eastern capital of Constantinople. Alfoldi (p. 110) draws attention to ‘the small bronze coins and medallions, issued in mass, on which the sceptre of the "Tyche", the goddess who personifies the city, is shown the globe of Christ - which means to say that the new capital is the ideal centre of the Christian world-empire.’ As Alfoldi (p. 116) explains, ‘On the shoulder of the personification of the New Rome is shown the globe of the world, set on the cross of Christ, symbolising the new capital of Christendom.’

Bruun (p. 63) is dismissive of Alfoldi’s interpretation of the supposed ‘cross-sceptre’ carried by the personification of Constantinopolis. On the basis of an examination of related issues, he argues convincingly that the ‘globe’ is no more than the globular end of a reversed spear, and that the cross-bar seen on many coins is in fact merely a two-dimensional representation of what was, in reality, a three-dimensional disc. Bruun accordingly contends that these issues convey no intended Christian significance.

(Fig. 7) Valentinian III; gold solidus; AD 455

(Fig. 7) Valentinian III; gold solidus; AD 455

Nevertheless, the supposed cross-sceptre was subsequently perceived by many to have possessed a Christian significance and, its original neutral status notwithstanding, it came to serve as a symbol of the Church in its own right. On the coinage, this survival is well demonstrated by an issue of large bronzes struck in the name of Valentinian II at Rome in AD 378-83. On these rare coins the emperor is portrayed bearing a cross sceptre tipped with a globular Chi-Rho, whilst on other later issues, the cross-sceptre is shown in a greatly simplified form.

Divus Constantinus

After his death in AD 337, Constantine was deified by the Senate, his sons issuing commemorative coins in his name in the traditional style. Eusebius (4.37) records that, "A coin … (had) on one side a figure of our blessed prince, with head closely veiled; the reverse showed him sitting as a charioteer drawn by four horses, with a hand stretched downward from above to receive him up to heaven".

(Fig. 8) Constantine the Great; posthumous bronze coin; AD 337-40

Burnett (p. 146) observes that the iconography of his metamorphosis, as represented on the coins struck to commemorate it, was Christianised: ‘Previous emperors had ridden up to heaven in a chariot; Constantine was received by the manus dei. The "hand of God" was, with the Chi-Rho monogram, one of the most important Christian symbols to appear on the coinage of the late empire.’ By way of illustration, a very similar image to that appearing on the coins of the deified Constantine may be observed on one of the panels of the early 5th century door of the Church of S. Sabina in Rome. There the Ascension of Elijah is portrayed, the prophet being conveyed heavenwards in a chariot with the divine assistance of an angel. The manus dei also appears on many coins, frequently crowning the emperor or his consort with a diadem or laurel wreath.

(Fig. 9) Galla Palacidia; gold solidus; AD 426-30

Conclusion

Whilst there can be little dispute that the Coinage of Constantine the Great did indeed express his religious convictions, it is equally true that it was not exceptionally rich in Christian symbolism. As Bruun (p. 64) reminds us however, ‘There was no independently Christian artistic tradition. The Christian ideas now about to conquer the State had to employ old means to express new conceptions.’

(Fig. 10) Honorius; gold solidus; AD 422

Constantine was nevertheless recognised by his contemporaries and near-contemporaries as the first Christian emperor, and through the writings of Eusebius, certain elements of his coinage came inextricably to be associated with the triumphant faith. As Bruun correctly records, ‘The victor is the official interpreter of history, and Christianity was the true victor of the Milvian Bridge and Chrysopolis. Thus Constantine’s victorious sign, his helmet, his seeming cross-sceptre and the aura around his head were adopted by posterity as Christian symbols, Christian signs of power.’ The Cross truly had triumphed.

(Fig. 11) Valentinian III; gold tremissis; AD 425-55

Bibliography

Alfoldi, A. (1948) The Conversion of Constantine and Pagan Rome, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bowder, D. (ed.) (1980) Who Was Who in the Roman World, Oxford: Phaidon.

Bruun, P. (1966) The Roman Imperial Coinage Vol. VII: Constantine and Licinius AD 313-337, London: Spink

Burnett, A. (1987) Coinage in the Roman World, London: Seaby.

Carson, R.A.G. (1981) Principal Coins of the Romans Vol. III: The Dominate, AD 294-498, London: British Museum Press.

L’Orange, H.P. (1947) Apotheosis in Ancient Portraiture, Oslo: Aschehoug.

L’Orange, H.P. (1965) Art Forms and Public Life in the late Roman Empire, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Parker, H.M.D. & Warmington, B.H. (1958) A History of the Roman World AD 138 to 337 (2nd ed.), London: Methuen.

Runciman, S. (1975) Byzantium: Style and Civilisation, London: Penguin.

Sutherland, C.H.V. (1955) Art in Coinage: The Aesthetics of Money from Greece to the Present Day, London: Batsford.

Toynbee, J.M.C. (1947) ‘Ruler Apotheosis in Ancient Rome’, Numismatic Chronicle.

Vermeule, C. (1978) ‘The Imperial Shield as a Mirror of Roman Art on Medallions and Coins’ in Carson, C. & Kraay, C.M. (eds.) Scripta Nummaria Romana: Essays Presented to Humphrey Sutherland, London: Spink.

Voght, J. (1965) The Decline of Rome: The Metamorphosis of Ancient Civilisation, London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Christian Symbolism on the Coinage of Constantine the Great

- Log in to post comments

313AD Edict of Milan (Edict of Toleration): Roman Empire signs peace deal with Christendom

Revelation 19:11-21

Now I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse. And He who sat on him was called Faithful and True, and in righteousness He judges and makes war. 12 His eyes were like a flame of fire, and on His head were many crowns. He had a name written that no one knew except Himself. 13 He was clothed with a robe dipped in blood, and His name is called The Word of God. 14 And the armies in heaven, clothed in fine linen, white and clean, followed Him on white horses. 15 Now out of His mouth goes a sharp sword, that with it He should strike the nations. And He Himself will rule them with a rod of iron. He Himself treads the winepress of the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God. 16 And He has on His robe and on His thigh a name written: KING OF KINGS AND LORD OF LORDS.

17 Then I saw an angel standing in the sun; and he cried with a loud voice, saying to all the birds that fly in the midst of heaven,"Come and gather together for the supper of the great God, 18 that you may eat the flesh of kings, the flesh of captains, the flesh of mighty men, the flesh of horses and of those who sit on them, and the flesh of all people, free and slave, both small and great."

19 And I saw the beast, the kings of the earth, and their armies, gathered together to make war against Him who sat on the horse and against His army. 20 Then the beast was captured, and with him the false prophet who worked signs in his presence, by which he deceived those who received the mark of the beast and those who worshiped his image. These two were cast alive into the lake of fire burning with brimstone. 21 And the rest were killed with the sword which proceeded from the mouth of Him who sat on the horse. And all the birds were filled with their flesh.

NKJV

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edict_of_Milan

Edict of Milan

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Edict of Milan was a letter signed by emperors Constantine and Licinius, that proclaimed religious toleration in the Roman Empire. The letter was issued in 313AD, shortly after the conclusion of the Diocletian Persecution.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Discussion

While it is true that Constantine and Licinius must have discussed religious policy when they met at Milan in February 313, the text usually called the Edict of Milan is in fact a letter to the Governor of Bithynia of June 313, one of a series of letters issued by Licinius in the territory he conquered from Maximinus in 313. Both toleration and restitution had already been granted by Constantine in Gaul, Spain and Britain (in 306), and by Maxentius in Italy and Africa (in 306 [toleration] and 310 [restitution]). Galerius and Licinius had enacted toleration in the Balkans in 311, and Licinius probably extended restitution there in early 313. Thus the letters which Licinius issued in the names of himself and Constantine (as was routine for imperial documents, which were formally issued in the names of all legitimate co-rulers) were designed solely to enact toleration and restitution in Anatolia and Oriens, which had been under the rule of Maximinus.

The Edict, in the form of a joint letter to be circulated among the governors of the East,[1] declared that the Empire would be neutral with regard to religious worship, officially removing all obstacles to the practice of Christianity and other religions.[2] It "declared unequivocally that the co-authors of the regulations wanted no action taken against the non-Christian cults."[3]

Christianity had previously been decriminalized in April 311 by Galerius, who was the first emperor to issue an edict of toleration for all religious creeds, including Christianity.[4] The Christian historian Philip Schaff noted that the second edict went beyond the first edict of 311: "it was a decisive step from hostile neutrality to friendly neutrality and protection, and prepared the way for the legal recognition of Christianity, as the religion of the empire."[5]The wording of the Edict reveals that such developments, however, remained in the future. The letter gives detailed instructions to the governor for the restitution of sequestered Christian property.

The Edict of Milan transformed the status of Christianity, as it initiated the period known by Christian historians as the Peace of the Church, and it has been interpreted by Christians as officially giving imperial favor to Christianity, as Constantine became the first emperor to actually promote and grant favors to the Church and its members.[6] The document itself does not survive.

[edit] History

The Edict of Milan was issued in 313 AD, in the names of the Roman Emperors Constantine I, who ruled the western parts of the Empire, and Licinius, who ruled the east. The two augusti were in Milan to celebrate the wedding of Constantine's sister with Licinius.

A previous edict of toleration had been recently issued by the emperor Galerius from Serdica and posted up at Nicomedia on 30 April, 311. By its provisions, the Christians, who had "followed such a caprice and had fallen into such a folly that they would not obey the institutes of antiquity", were granted an indulgence.

Wherefore, for this our indulgence, they ought to pray to their God for our safety, for that of the republic, and for their own, that the commonwealth may continue uninjured on every side, and that they may be able to live securely in their homes.

By the Edict of Milan the meeting places and other properties which had been confiscated from the Christians and sold or granted out of the government treasury were to be returned:

...the same shall be restored to the Christians without payment or any claim of recompense and without any kind of fraud or deception...

It directed the provincial magistrates to execute this order at once with all energy, so that public order may be restored and the continuance of the Divine favor may "preserve and prosper our successes together with the good of the state."

The actual edicts have not been retrieved inscribed upon stone. However, they are quoted at length in a historical work with a theme of divine retribution, Lactantius' De mortibus persecutorum ("Deaths of the persecutors"), who gives the Latin text of both Galerius's Edict of Toleration as posted up at Nicomedia on 30 April 311, and of Licinius's letter of toleration and restitution addressed to the governor of Bithynia, posted up also at Nicomedia on 13 June 313. Eusebius of Caesarea translated both into Greek in his History of the Church (Historia Ecclesiastica). His version of the letter of Licinius must derive from a copy as posted up in Palestine (probably at Caesarea) in the late summer or early autumn of 313, but the origin of his copy of Galerius's edit of 311 is unknown, since that does not seem to have been promulgated in Palestine.

[edit] References

- ^ It brought the governance of the Eastern Empire into line with the tolerance now operating in Constantine's dominions in the West. The Edict's context in Constantine's career is explored in John Curran, "Constantine and the Ancient Cults of Rome: The Legal Evidence" Greece & Rome 2nd Series 43.1 (April 1996, pp 68-80): Edict of Milan, p. 68f.

- ^ "...we have also conceded to other religions the right of open and free observance of their worship for the sake of the peace of our times, that each one may have the free opportunity to worship as he pleases; this regulation is made we that we may not seem to detract from any dignity or any religion." Edict of Milan as quoted by Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum ("On the Deaths of the Persecutors") chapters 34, 35.

- ^ Curran 1996:69, quoting the Edict: "This we have done to ensure that no cult or religion may seem to have been impaired by us."

- ^ Lactantius, op. cit.. The theme of the work is the divine retribution that befell the perpetrators of the persecution ended by the decree of Galerius.

- ^ History of the Christian Church, chapter II, section 25 on-line text "The Edicts of Toleration. a.d. 311–313".

- ^ "In the Ecclesiastical History, the Panegyric on Constantine and the life of Constantine... the guiding idea of Eusebius is the establishment of a Christian empire, of which Constantine was the chosen instrument" (J.B. Bury, editor, Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vol. II, Appendix, p. 359).

[edit] External links

- Log in to post comments

313AD --> : The Peace of the Church

Revelation 19:11-21

Now I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse. And He who sat on him was called Faithful and True, and in righteousness He judges and makes war. 12 His eyes were like a flame of fire, and on His head were many crowns. He had a name written that no one knew except Himself. 13 He was clothed with a robe dipped in blood, and His name is called The Word of God. 14 And the armies in heaven, clothed in fine linen, white and clean, followed Him on white horses. 15 Now out of His mouth goes a sharp sword, that with it He should strike the nations. And He Himself will rule them with a rod of iron. He Himself treads the winepress of the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God. 16 And He has on His robe and on His thigh a name written: KING OF KINGS AND LORD OF LORDS.

17 Then I saw an angel standing in the sun; and he cried with a loud voice, saying to all the birds that fly in the midst of heaven,"Come and gather together for the supper of the great God, 18 that you may eat the flesh of kings, the flesh of captains, the flesh of mighty men, the flesh of horses and of those who sit on them, and the flesh of all people, free and slave, both small and great."

19 And I saw the beast, the kings of the earth, and their armies, gathered together to make war against Him who sat on the horse and against His army. 20 Then the beast was captured, and with him the false prophet who worked signs in his presence, by which he deceived those who received the mark of the beast and those who worshiped his image. These two were cast alive into the lake of fire burning with brimstone. 21 And the rest were killed with the sword which proceeded from the mouth of Him who sat on the horse. And all the birds were filled with their flesh.

NKJV

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peace_of_the_Church

Peace of the Church

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Peace of the Church is a designation usually applied to the condition of the Church after the publication of the Edict of Milan in 313 by the two Augusti, Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and his eastern colleague Licinius, an edict of toleration by which the Christians were accorded complete liberty to practise their religion without molestation.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Antecedents

The Roman state had always granted its Pagan polytheistic cult the status of state religion, and the same social elite (originally mainly Patricians) provided its major priests as well as its politicians and generals. For centuries this was easily compatible with the Pagan religions of conquered peoples, whose divinities were generally equated to Roman ones or adopted into the Roman Pantheon. But just as pharaoh Echnaton's monotheistic cult of Aton proved incompatible with Egypt's traditional polytheism, the Judeo-Christian instistence on Yahweh being the only God, believing all other gods are false gods, could not be fitted into the system that had allowed religious peace throughout the empire. The massive spread of Christians, first looked on merely as Jewish schismatics, over most provinces and Rome itself, and most of all their refusal of the state-imposed emperor cult, was logically perceived as a threat not just to the state cult, but to the state itself, leading to systematical persecution.

A new stage was reached when, in the middle of the third century, the Church as such was made the object of attack. This attitude, inaugurated by Emperor Decius (249 - 251), made the issue at stake clear and well-defined. The imperial authorities convinced themselves that the Christian Church and the Pagan Roman State could not co-exist; henceforth but one solution was possible, the destruction of Christianity or the conversion of Rome. For half a century the result was in doubt. The failure of Diocletian (284-305) and his Tetrarchy colleagues in the last and bloodiest persecution to shake the resolution of the Christians or to annihilate the Church left no course open to prudent statesmen but to recognize the inevitable and to abandon the old concept of government, the union of civil power and Paganism.