FIRE-ONGOING Satan in Lake of Fire

REFORMATION-ONGOING No more Satan

REFORMATION-ONGOING: No Satan

REFORMATION-ONGOING: Kingdom Lost | Kingdom No End

REFORMATION-FOREVER: Kingdom End | Kingdom No End

REFORMATION-FOREVER: Kingdom Taken Away | Kingdom No End

REFORMATION-FOREVER: Captivity | Kingdom without End

REFORMATION-FOREVER: Exile | Kingdom without End

REFORMATION-FOREVER: Kingdom no end, no Satan

This is where the analogy between the histories of Old Testament Israel and New Testament Christianity part ways. Following its miraculous deliverance from Heaven by and angel during Hezekiah's reign, Old Testament Israel (Judah harboring the remnant of Israel) degraded under evil kings once again into sin, sieges and ultimately, Exile: this was when God announced that, though He would restore natural Israel for a season, He determined to keep it on life support just long enough to usher in a new covenant. In contrast, following its miraculous deliverance from Heaven by the Fires of the Reformation, New Testament Christianity has risen under King Jesus the Christ into fuller and fuller manifestation of the glorious liberty of the sons of God in His Everlasting Kingdom that has no end. Glory to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!

[ I would add the clarification that this "fire from heaven," this "zeal of the Saints," continues to abide with Christians, continually vigilant to subjugate evil in the World around us, whereby the Saints reign over evil. Recall, also, the "tongues of fire," that lit upon the Saints at Pentecost, accompanying their baptism in the Holy Spirit along with the speaking in tongues. Recall, also, John the Baptist's teaching that Christ would baptize "with the Holy Spirit and fire." ]

Satan, the organizational head of evil beings, will never again organize the world into idol-worshipping empires as he did in the ancient world, (the various "beasts" of Daniel & Revelation). This does not mean there remain no more evil, or sin, or temptors, etc. It only means that evil beings & temptors lack the organizational head, (Satan), they once had when the world was subjugated beneath idol-worshipping superpowers. Evil beings such as the ancient principalities and powers, (Eph 6:12), are present, (and people still follow their sorceries, Rev 22:15), but they are positioned now only as disorganized insurgents outside the protected "Green Zone," the reigning City of God, the holy Heavenly & New Jerusalem, the eternal ruling empire of Christ, Christendom. The organizational head of evil, the Devil, Satan, has been cast into the Lake of Fire which is the Second Death, Rev 20:10. How much more confidence we should have today to resist evil and temptation, washing our robes in the river flowing from the City, that we might enter the Gates of the City and serve our holy Father & Christ our Lord, reigning with them forever! Amen.

The following events in history are given to show how history lives up to the hope anticpated by this view.

- Log in to post comments

1451-1506AD Christopher Columbus: Discovery of the New World

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Columbus

Christopher Columbus

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Christopher Columbus | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Alejo Fernández, painted between 1505 and 1536. Photo by historian Manuel Rosa. | |

| Born | c. 1451 disputed, Genoa, Italy |

| Died | May 20, 1506 outside Valladolid, Spain |

| Occupation | Maritime explorer for the Crown of Castile |

| Religious stance | Christianity |

Christopher Columbus (1451 – May 20, 1506) was a navigator, colonizer, and explorer and one of the first Europeans to explore the Americas after the Vikings. Though not the first to reach the Americas from Europe, Columbus' voyages led to general European awareness of the hemisphere and the successful establishment of European cultures in the New World. It is generally believed that he was born in Genoa, although other theories exist. The name Christopher Columbus is the Anglicization of the Latin Christophorus Columbus. Also well known are his name's rendering in modern Italian as Cristoforo Colombo and in Spanish as Cristóbal Colón.

Columbus' voyages across the Atlantic Ocean began a European effort at exploration and colonization of the Western Hemisphere. While history places great significance on his first voyage of 1492, he did not actually reach the South American mainland until his third voyage in 1498. Instead, he made landfall on an island in the Bahamas Archipelago that he named San Salvador while trying to find a sea route to India, hence the indigenous inhabitants being called "Indians". Likewise, he was not the earliest European explorer to reach the Americas, and there are accounts of European transatlantic contact prior to 1492. Nevertheless, Columbus's voyage came at a critical time of growing national imperialism and economic competition between developing nation states seeking wealth from the establishment of trade routes and colonies. The term Pre-Columbian is sometimes used to refer to the peoples and cultures of the Americas before the arrival of Columbus and further European influence.

The anniversary of the 1492 voyage (vd. Columbus Day) is observed throughout the Americas and in Spain.

Contents[hide] |

Nationality

It is most widely accepted that Columbus was born in the Republic of Genoa, located in modern-day Italy.[1] 188 notarial, judicial, and administrative documents about Cristoforo Colombo (Christopher Columbus) and his family have been preserved in the "Archivio di Stato" (national record office) of Genoa, Italy.[2] Some writers hold that his background was Spanish, Portuguese or Greek,[3] but no conclusive evidence has ever been offered. Clues to Columbus' origin such as learned languages and DNA samples have been studied, but to date, DNA tests show only that Columbus was Caucasian, and probably was not (as some have argued) a Sephardic Jew (Spanish/Portuguese).[4] DNA surveys of present-day individuals with similar names in various countries are continuing.[5] There was one document, the Last Will and Testament of 1498, where Columbus said he was from Genoa, but it is said to have been falsified, by the Spaniards, in 1573 (67 years after Columbus's death, along with certain other documents that supported this theory). [6] However, there is proof in the memoirs of England's King Henry VII (who was prepared to finance Columbus's voyage but was beat to it by the Spaniards) that Columbus's brother had visited him frequently regarding Columbus's planned exploration and that the king had used his Royal translator, familiar with the dialect spoken in Genoa, Italy, to communicate with the visitor. King Henry VII identified the visitor as an Italian from Genoa[citation needed]. A gloss journal of Columbus's, written in Italian, was kept by the Royal Court of Spain[citation needed]. A study made on Columbus's Spanish letters concluded that he wasn't a native speaker of a dialect of Spain. His journals, which were written in an extremely substandard form of Spanish mixed with Catalan and Portuguese, are proof that he wasn't an original inhabitant of Spain. His combination of languages is generally accepted as a learned way that Columbus, an uneducated twelve-year old from Genoa who set sail on a ship to Portugal, had eventually (through travels in Portugal and Spain) created this pidgin form of Iberian languages. Columbus's wide knowledge of the sea led to his first marriage to a noble Portuguese woman, Felipa Moniz Perestrello, who was the daughter of Bartolomeo Perestrello, an Italian aristocrat from the Parma region of Italy.[citation needed]). This type of "reward" marriage had been typical in Europe throughout the ages. Many such rewards (as well as fortunes and noble titles) had been bestowed on middle-class and impoverished peoples throughout time by European nobles as rewards for their ideas and accopmlishments. It is commonly accepted that Columbus was not a Spaniard nobleman as some have implied. Most people worldwide find it unimaginable that a noble, educated Spaniard would write in a pidgin form of Iberian languages instead of in proper Spanish. Many of the letters that Columbus wrote to Italian people, some of them even from Genoa, were not written in Italian, but in a substandard, pidgin form of Iberian languages.

Early life

According to the most widely acknowledged biographies, Columbus was born between August and October 1451 in Genoa. His father was Domenico Colombo, a middle-class wool weaver working between Genoa and Savona. His mother was Susanna Fontanarossa. Bartolomeo, Giovanni Pellegrino and Giacomo were his brothers. Bartolomeo worked in a cartography workshop in Lisbon for at least part of his adulthood.[1]

While information about Columbus' early years is scarce, he probably received an incomplete education. He spoke a Genoese dialect. In one of his writings, Columbus claims to have gone to the sea at the age of 10. In 1470 the Columbus Family moved to Savona, where Domenico took over a tavern. In the same year, Columbus was on a Genoese ship hired in the service of René I of Anjou to support his attempt to conquer the Kingdom of Naples.

In 1473 Columbus began his apprenticeship as business agent for the important Centurione, Di Negro and Spinola families of Genoa. Later he allegedly made a trip to Chios, in the Aegean Sea. In May 1476, he took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry a valuable cargo to northern Europe. He docked in Bristol, Galway, in Ireland and very likely, in 1477 he was in Iceland. In 1479 Columbus reached his brother Bartolomeo in Lisbon, keeping on trading for the Centurione family. He married Filipa Moniz Perestrello, daughter of the Porto Santo governor, Bartolomeo Perestrello. In 1481, his son, Diego was born.

Physical appearance

Although an abundance of artwork involving Christopher Columbus exists, no authentic contemporary portrait has been found. The only official portrait was painted by Alejo Fernández, between 1505 and 1536, titled Virgen de los Navegantes in the Royal Alcazar in Seville. In 1595 Theodore de Bry made an etching after a painting of Columbus, made in his lifetime.[7] The etching shows resemblance with the portrait of Sebastiano del Piombo, so this painting might depict Columbus with some accuracy. Over the years, artists who reconstruct his appearance have done so from written descriptions. These writings describe him as having reddish hair, which turned to white early in his life, as well as being a lighter skinned person with too much sun exposure turning his face red.

Despite the clear description of auburn hair or (later) white hair, textbooks use the Sebastiano del Piombo painting so often that it has become the iconic image of Columbus accepted by popular culture.

Language

Although Genoese documents have been kept about a weaver named Colombo, some letters which are said to have been written by Columbus are written in an extremely nonstandard form of Spanish influenced by Portuguese or Catalan phonetics. He used this mixture when writing personal notes to himself, to his brother, Italian friends, and to the Bank of Genoa. Two of his brothers, also accepted as being wool weavers from Genoa, possibly understood and wrote this form of Spanish/Portuguese as well. Genoese Italian was a language generally written by Genoa's schooled people at that time; the average person from Genoa naturally spoke a Genoese variant of Italian.

In later years, Columbus mastered the use of Latin. He kept a journal in Latin as well as a more private journal in Greek.

Background to voyages

Navigation plans

Europe had long enjoyed a safe land passage to China and India— sources of valued goods such as silk, spices, and opiates— under the hegemony of the Mongol Empire (the Pax Mongolica, or Mongol peace). With the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the land route to Asia became more difficult. The Columbus brothers had a different idea. By the 1480s, they had developed a plan to travel to the Indies, then construed roughly as all of south and east Asia, by sailing directly west across the "Ocean Sea," i.e., the Atlantic.

Following Washington Irving's 1828 biography of Columbus, Americans commonly believed Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan because Europeans thought the Earth was flat.[9] In fact, the primitive maritime navigation of the time relied on the stars and the curvature of the spherical Earth. The European knowledge of the diameter of the Earth had improved since the Renaissance which started a few decades previously, and this knowledge had spread between sailors and navigators[10]. This had been the general opinion of ancient Greek science, and continued as the second opinion (for example of Bede in The Reckoning of Time). In fact the Earth had generally been believed to be spherical since the 4th century BCE by most scholars and almost all navigators[citation needed], and Eratosthenes had measured the diameter of the Earth with good precision in the second century BC[11]. Columbus put forth (incorrect) arguments based on a significantly smaller diameter for the Earth, claiming that Asia could be easily reached by sailing west across the Atlantic. Most scholars accepted Ptolemy's correct assessment that the terrestrial landmass (for Europeans of the time, comprising Eurasia and Africa) occupied 180 degrees of the terrestrial sphere, and correctly dismissed Columbus's claim that the Earth was much smaller, and that Asia was only a few thousand nautical miles to the west of Europe. Columbus' error was put down to his lack of experience in navigation at sea[12].

Columbus, believed the (incorrect) calculations of Marinus of Tyre, putting the landmass at 225 degrees, leaving only 135 degrees of water. Moreover, Columbus believed that one degree represented a shorter distance on the earth's surface than was actually the case. Finally, he read maps as if the distances were calculated in Italian miles (1,238 meters). Accepting the length of a degree to be 56⅔ miles, from the writings of Alfraganus, he therefore calculated the circumference of the Earth as 25,255 kilometers at most, and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan as 3,000 Italian miles (3,700 km, or 2,300 statute miles) Columbus did not realize Al-Farghani used the much longer Arabic mile (about 1,830 m).

The main problem was that experts did not accept his estimate. The true circumference of the Earth is about 40,000 km (25,000 sm), a figure established by Eratosthenes in the second century BC,[13] and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan 19,600 km (12,200 sm). No ship that was readily available in the 15th century could carry enough food and fresh water for such a journey. Most European sailors and navigators concluded, likely correctly, that sailors undertaking a westward voyage from Europe to Asia non-stop would die of thirst or starvation long before reaching their destination. Spain, however, having completed an expensive war, was desperate for a competitive edge over other European countries in trade with the East Indies. Columbus promised such an advantage.

While Columbus' calculations underestimated the circumference of the Earth and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan by the standards of his peers as well as in fact, almost all Europeans held the mistaken opinion that the aquatic expanse between Europe and Asia was uninterrupted. As the 16th century developed it was the route to America, rather than to Japan, that gave Spain a competitive edge in developing an overseas empire.

Funding campaign

In 1485, Columbus presented his plans to John II, King of Portugal. He proposed the king equip three sturdy ships and grant Columbus one year's time to sail out into the Atlantic, search for a western route to Orient, and then return home. Columbus also requested he be made "Great Admiral of the Ocean", created governor of any and all lands he discovered, and given one-tenth of all revenue from those lands discovered. The king submitted the proposal to his experts, who rejected it. It was their considered opinion that Columbus' proposed route of 2,400 miles (3,860 km) was, in fact, far too short.[14]

In 1488 Columbus appealed to the court of Portugal once again, and once again John invited him to an audience. It too was to come to nothing, for not long afterwards came the arrival of Portugal's native son Bartholomeu Dias from a successful rounding of the southern tip of Africa. Portugal was no longer interested in trailblazing a western route to the East.

Columbus traveled from Portugal once more to both Genoa and Venice, but he received encouragement from neither. Previously he had his brother sound out Henry VII of England, to see if the English monarch might not be more amenable to Columbus' proposal. After much carefully considered hesitation Henry's invitation came, too late. Columbus had already committed himself to Spain.

He had sought an audience from the monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, who had united the largest kingdoms of Spain by marrying, and were ruling together. On May 1, 1486, permission having been granted, Columbus laid his plans before Queen Isabella, who, in turn, referred it to a committee. After the passing of much time, these savants of Spain, like their counterparts in Portugal, reported back that Columbus had judged the distance to Asia much too short. They pronounced the idea impractical, and advised their Royal Highnesses to pass on the proposed venture.

However, to keep Columbus from taking his ideas elsewhere, and perhaps to keep their options open, the King and Queen of Spain gave him an annual annuity of 12,000 maravedis ($840) and in 1489 furnished him with a letter ordering all Spanish cities and towns to provide him food and lodging at no cost.[15]

After continually lobbying at the Spanish court, he finally had success in 1492. Ferdinand and Isabella had just conquered Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian peninsula, and they received Columbus in Córdoba, in the Alcázar castle. Isabella turned Columbus down on the advice of her confessor, and he was leaving town in despair, when Ferdinand intervened. Isabella then sent a royal guard to fetch him and Ferdinand later rightfully claimed credit for being "the principal cause why those islands were discovered". King Ferdinand is referred to as "losing his patience" in this issue, but this cannot be proven.

About half of the financing was to come from private Italian investors, whom Columbus had already lined up. Financially broke after the Granada campaign, the monarchs left it to the royal treasurer to shift funds among various royal accounts on behalf of the enterprise. Columbus was to be made "Admiral of the Seas" and would receive a portion of all profits. The terms were unusually generous, but as his own son later wrote, the monarchs did not really expect him to return.

According to the contract that Columbus made with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, if Columbus discovered any new islands or mainland, he would receive many high rewards. In terms of power, he would be given the rank of Admiral of the Ocean Sea (Atlantic Ocean) and appointed Viceroy and Governor of all the new lands. He had the right to nominate three persons, from whom the sovereigns would choose one, for any office in the new lands. He would be entitled to 10 percent of all the revenues from the new lands in perpetuity; this part was denied to him in the contract, although it was one of his demands. Finally, he would also have the option of buying one-eighth interest in any commercial venture with the new lands and receive one-eighth of the profits.

Columbus was later arrested in 1500 and supplanted from these posts. After his death, Columbus's sons, Diego and Fernando, took legal action to enforce their father's contract. Many of the smears against Columbus were initiated by the Spanish crown during these lengthy court cases, known as the pleitos colombinos. The family had some success in their first litigation, as a judgment of 1511 confirmed Diego's position as Viceroy, but reduced his powers. Diego resumed litigation in 1512, which lasted until 1536, and further disputes continued until 1790.[16]

Voyages

First voyage

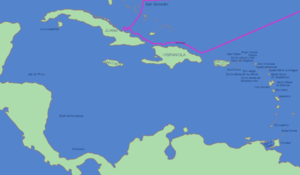

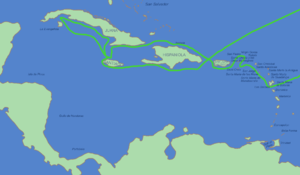

On the evening of August 3, 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera with three ships; one larger carrack, Santa María, nicknamed Gallega (the Gallician), and two smaller caravels, Pinta (the Painted) and Santa Clara, nicknamed Niña (the Girl). (The ships were never officially named).[citation needed] They were property of Juan de la Cosa and the Pinzón brothers (Martin Alonzo and Vicente Yáñez), but the monarchs forced the Palos inhabitants to contribute to the expedition. Columbus first sailed to the Canary Islands, which were owned by Castile, where he restocked the provisions and made repairs, and on September 6, he started what turned out to be a five-week voyage across the ocean.

Land was sighted at 2 a.m. on October 12, 1492, by a sailor named Rodrigo de Triana (also known as Juan Rodríguez Bermejo) aboard Pinta.[17] (Columbus would claim the prize.) Columbus called the island (in what is now The Bahamas) San Salvador, although the natives called it Guanahani. Exactly which island in the Bahamas this corresponds to is an unresolved topic; prime candidates are Samana Cay, Plana Cays, or San Salvador Island (named San Salvador in 1925 in the belief that it was Columbus's San Salvador). The indigenous people he encountered, the Lucayan, Taíno or Arawak, were peaceful and friendly. In his journal he wrote of them, "It appears to me, that the people are ingenious, and would be good servants and I am of opinion that they would very readily become Christians, as they appear to have no religion."[18] He also wrote of them, two days after landing, "I could conquer the whole of them with 50 men, and govern them as I pleased."[18]

Columbus also explored the northeast coast of Cuba (landed on October 28) and the northern coast of Hispaniola, by December 5. Here, the Santa Maria ran aground on Christmas morning 1492 and had to be abandoned. He was received by the native cacique Guacanagari, who gave him permission to leave some of his men behind. Columbus left 39 men and founded the settlement of La Navidad in what is now present-day Haiti. Before returning to Spain, Columbus also kidnapped some ten to twenty-five Indians and took them back with him. Only seven or eight of the Indians arrived in Spain alive, but they made quite an impression on Seville.[17]

Columbus headed for Spain, but another storm forced him into Lisbon. He anchored next to the King's harbor patrol ship on March 4, 1493 in Portugal. After spending more than one week in Portugal, he set sail for Spain. He reached Spain on March 15, 1493. Word of his finding new lands rapidly spread throughout Europe.

Second voyage

Columbus left Cádiz, Spain, on September 24, 1493 to find new territories, with 17 ships carrying supplies, and about 1,200 men to colonize the region. On October 13, the ships left the Canary Islands as they had on the first voyage, following a more southerly course.

On November 3, 1493, Columbus sighted a rugged island that he named Dominica (Latin for Sunday); later that day, he landed at Marie-Galante, which he named Santa Maria la Galante. After sailing past Les Saintes (Los Santos, The Saints), he arrived at Guadeloupe (Santa María de Guadalupe de Extremadura, after the image of the Virgin Mary venerated at the Spanish monastery of Villuercas, in Guadalupe, Spain), which he explored between November 4 and November 10, 1493.

The exact course of his voyage through the Lesser Antilles is debated, but it seems likely that he turned north, sighting and naming several islands, including Montserrat (for Santa Maria de Montserrate, after the Blessed Virgin of the Monastery of Montserrat, which is located on the Mountain of Montserrat, in Catalonia, Spain), Antigua (after a church in Seville, Spain, called Santa Maria la Antigua, meaning "Old St. Mary's"), Redonda (for Santa Maria la Redonda, Spanish for "round", owing to the island's shape), Nevis (derived from the Spanish, Nuestra Señora de las Nieves, meaning "Our Lady of the Snows", because Columbus thought the clouds over Nevis Peak made the island resemble a snow-capped mountain), Saint Kitts (for St. Christopher, patron of sailors and travelers), Sint Eustatius (for the early Roman martyr, St. Eustachius), Saba (also for St. Christopher?), Saint Martin (San Martin), and Saint Croix (Santa Cruz, meaning "Holy Cross"). He also sighted the island chain of the Virgin Islands (and named them Islas de Santa Ursula y las Once Mil Virgenes, Saint Ursula and the 11,000 Virgins, a cumbersome name that was usually shortened, both on maps of the time and in common parlance, to Islas Virgenes), and he also named the islands of Virgin Gorda (the fat virgin), Tortola, and Peter Island (San Pedro).

He continued to the Greater Antilles, and landed at Puerto Rico (originally San Juan Bautista, in honor of Saint John the Baptist, a name that was later supplanted by Puerto Rico (English: Rich Port) while the capital retained the name, San Juan) on November 19, 1493. One of the first skirmishes between native Americans and Europeans since the time of the Vikings[19] took place when Columbus's men rescued two boys who had just been castrated by their captors.

On November 22, Columbus returned to Hispaniola, where he intended to visit Fuerte de la Navidad (Christmas Fort), built during his first voyage, and located on the northern coast of Haiti; Fuerte de la Navidad was found in ruins, destroyed by the native Taino people, whereupon, Columbus moved more than 100 kilometers eastwards, establishing a new settlement, which he called La Isabela, likewise on the northern coast of Hispaniola, in the present-day Dominican Republic. However, La Isabela proved to be a poorly-chosen location, and the settlement was short-lived.

He left Hispaniola on April 24, 1494, arrived at Cuba (naming it Juana) on April 30. He explored the southern coast of Cuba, which he believed to be a peninsula rather than an island, and several nearby islands, including the Isle of Pines (Isla de las Pinas, later known as La Evangelista, The Evangelist). He reached Jamaica on May 5. He retraced his route to Hispaniola, arriving on August 20, before he finally returned to Spain.

During this second trip, the rape of an indigenous woman was reported by one of Columbus's crew (Michel de Cuneo) and with Columbus's tolerance:

When I was in the ship, I turned into captivity a beautiful caribe woman, given to me as a gift by the Almirant, and after I took her to my stateroom, and while she was naked as their custom is, I felt desires of laying with her. I want to satisfy my desire but she didn’t want and gave me such a treatment with her nails that I think it would be better to never begun. But when I saw this (and to tell you everything up to the end), I take a rope and whipped her, after what she screamed a lot, in such a way you cannot believe your ears. Finally we reached such an agreement that I can tell you she appeared to be trained in a whore school.

Original text:

Mientras estaba en la barca, hice cautiva a una hermosísima mujer caribe, que el susodicho Almirante me regaló, y después que la hube llevado a mi camarote, y estando ella desnuda según es su costumbre, sentí deseos de holgar con ella. Quise cumplir mi deseo pero ella no lo consintió y me dió tal trato con sus uñas que hubiera preferido no haber empezado nunca. Pero al ver esto (y para contártelo todo hasta el final), tomé una cuerda y le di de azotes, después de los cuales echó grandes gritos, tales que no hubieras podido creer tus oídos. Finalmente llegamos a estar tan de acuerdo que puedo decirte que parecía haber sido criada en una escuela de putas.[20]

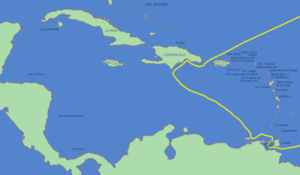

Third voyage

On May 30, 1498, Columbus left with six ships from Sanlúcar, Spain, for his third trip to the New World. He was accompanied by the young Bartolomé de Las Casas, who would later provide partial transcripts of Columbus' logs.

Columbus led the fleet to the Portuguese island of Porto Santo, his wife's native land. He then sailed to Madeira and spent some time there with the Portuguese captain João Gonçalves da Camara before sailing to the Canary Islands and Cape Verde. Columbus landed on the south coast of the island of Trinidad on July 31. From August 4 through August 12, he explored the Gulf of Paria which separates Trinidad from Venezuela. He explored the mainland of South America, including the Orinoco River. He also sailed to the islands of Chacachacare and Margarita Island and sighted and named Tobago (Bella Forma) and Grenada (Concepcion).

Columbus returned to Hispaniola on August 19 to find that many of the Spanish settlers of the new colony were discontented, having been misled by Columbus about the supposedly bountiful riches of the new world. An entry in his journal from September 1498 reads, "From here one might send, in the name of the Holy Trinity, as many slaves as could be sold..." Indeed, as a fierce supporter of slavery, Columbus ultimately refused to baptize the native people of Hispanolia, since Catholic law forbade the enslavement of Christians. [21]

Columbus repeatedly had to deal with rebellious settlers and natives.[citation needed] He had some of his crew hanged for disobeying him. A number of returning settlers and sailors lobbied against Columbus at the Spanish court, accusing him and his brothers of gross mismanagement. On his return he was arrested for a period (see Governorship and arrest section below).

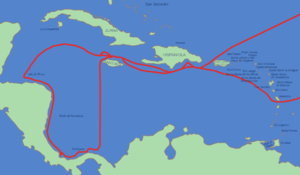

Fourth voyage

Columbus made a fourth voyage nominally in search of the Strait of Malacca to the Indian Ocean. Accompanied by his brother Bartolomeo and his 13-year-old son Fernando, he left Cádiz, Spain, on May 11, 1502, with the ships Capitana, Gallega, Vizcaína and Santiago de Palos. He sailed to Arzila on the Moroccan coast to rescue Portuguese soldiers whom he had heard were under siege by the Moors. On June 15, they landed at Carbet on the island of Martinique (Martinica). A hurricane was brewing, so he continued on, hoping to find shelter on Hispaniola. He arrived at Santo Domingo on June 29, but was denied port, and the new governor refused to listen to his storm prediction. Instead, while Columbus' ships sheltered at the mouth of the Rio Jaina, the first Spanish treasure fleet sailed into the hurricane. Columbus' ships survived with only minor damage, while twenty-nine of the thirty ships in the governor's fleet were lost to the July 1st storm. In addition to the ships, 500 lives (including that of the governor, Francisco de Bobadilla) and an immense cargo of gold were surrendered to the sea.

After a brief stop at Jamaica, Columbus sailed to Central America, arriving at Guanaja (Isla de Pinos) in the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras on July 30. Here Bartolomeo found native merchants and a large canoe, which was described as "long as a galley" and was filled with cargo. On August 14, he landed on the American mainland at Puerto Castilla, near Trujillo, Honduras. He spent two months exploring the coasts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, before arriving in Almirante Bay, Panama on October 16.

On December 5, 1502, Columbus and his crew found themselves in a storm unlike any they had ever experienced. In his journal Columbus writes,

For nine days I was as one lost, without hope of life. Eyes never beheld the sea so angry, so high, so covered with foam. The wind not only prevented our progress, but offered no opportunity to run behind any headland for shelter; hence we were forced to keep out in this bloody ocean, seething like a pot on a hot fire. Never did the sky look more terrible; for one whole day and night it blazed like a furnace, and the lightning broke with such violence that each time I wondered if it had carried off my spars and sails; the flashes came with such fury and frightfulness that we all thought that the ship would be blasted. All this time the water never ceased to fall from the sky; I do not say it rained, for it was like another deluge. The men were so worn out that they longed for death to end their dreadful suffering.[22]

In Panama, Columbus learned from the natives of gold and a strait to another ocean. After much exploration, in January 1503 he established a garrison at the mouth of the Rio Belen. On April 6 one of the ships became stranded in the river. At the same time, the garrison was attacked, and the other ships were damaged. Columbus left for Hispaniola on April 16, heading north. On May 10 he sighted the Cayman Islands, naming them "Las Tortugas" after the numerous sea turtles there. His ships next sustained more damage in a storm off the coast of Cuba. Unable to travel farther, on June 25, 1503, they were beached in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica.

For a year Columbus and his men remained stranded on Jamaica. A Spaniard, Diego Mendez, and some natives paddled a canoe to get help from Hispaniola. That island's governor, Nicolás de Ovando, detested Columbus and obstructed all efforts to rescue him and his men. In the meantime Columbus, in a desperate effort to induce the natives to continue provisioning him and his hungry men, successfully intimidated the natives by correctly predicting a lunar eclipse for February 29, 1504, using the Ephemeris of the German astronomer Regiomontanus.[23] Help finally arrived, no thanks to the governor, on June 29, 1504, and Columbus and his men arrived in Sanlúcar, Spain, on November 7.

Governorship and arrest

During Columbus' stint as governor and viceroy, disgruntled Spaniards, who chafed at being governed by an Italian, had claimed that he had ruled his domain tyrannically[citation needed]. Columbus was physically and mentally exhausted; his body was wracked by arthritis and his eyes by ophthalmia. In October 1499, he sent two ships to Spain, asking the Court of Spain to appoint a royal commissioner to help him govern.

The Court appointed Francisco de Bobadilla, a member of the Order of Calatrava; however, his authority stretched far beyond what Columbus had requested. Bobadilla was given total control as governor from 1500 until his death in 1502. Arriving in Santo Domingo while Columbus was away, Bobadilla was immediately peppered with complaints about all three Columbus brothers: Christopher, Bartolomé, and Diego. Consuelo Varela, a Spanish historian, states: "Even those who loved him [Columbus] had to admit the atrocities that had taken place."[24][25]

As a result of these testimonies, Columbus upon his return, without being allowed a word in his own defense, had been clapped into manacles on his arms and chains on his feet and cast into prison to await return to Spain. He was 53 years old.

On October 1, 1500, Columbus and his two brothers, likewise in chains, were sent back to Spain. Once in Cádiz, a grieving Columbus wrote to a friend at court:

It is now seventeen years since I came to serve these princes with the Enterprise of the Indies. They made me pass eight of them in discussion, and at the end rejected it as a thing of jest. Nevertheless I persisted therein... Over there I have placed under their sovereignty more land than there is in Africa and Europe, and more than 1,700 islands... In seven years I, by the divine will, made that conquest. At a time when I was entitled to expect rewards and retirement, I was incontinently arrested and sent home loaded with chains... The accusation was brought out of malice on the basis of charges made by civilians who had revolted and wished to take possession on the land....

I beg your graces, with the zeal of faithful Christians in whom their Highnesses have confidence, to read all my papers, and to consider how I, who came from so far to serve these princes... now at the end of my days have been despoiled of my honor and my property without cause, wherein is neither justice nor mercy.[26]

According to testimony of 23 witnesses during his trial, Columbus regularly used barbaric acts of torture to govern Hispaniola. [27]

Columbus and his brothers lingered in jail for six weeks before the busy King Ferdinand ordered their release. Not long thereafter, the king and queen summoned the Columbus brothers to their presence at the Alhambra palace in Granada. There the royal couple heard the brothers' pleas; restored their freedom and their wealth; and, after much persuasion, agreed to fund Columbus' fourth voyage. But the door was firmly shut on Christopher Columbus's role as governor. From that point forward, Don Nicolás de Ovando was to be the new governor of the West Indies.

Later life

While Columbus had always given the conversion of non-believers as one reason for his explorations, he grew increasingly religious in his later years. He claimed to hear divine voices, lobbied for a new crusade to capture Jerusalem, often wore Franciscan habit, and described his explorations to the "paradise" as part of God's plan which would soon result in the Last Judgment and the end of the world.

In his later years, Columbus demanded that the Spanish Crown give him 10% of all profits made in the new lands, pursuant to earlier agreements. Because he had been relieved of his duties as governor, the crown did not feel bound by these contracts, and his demands were rejected. After his death his family later sued for part of the profits from trade with America in the pliegos colombinos.

On May 20, 1506, at about the age of 55, Columbus died in Valladolid, fairly wealthy from the gold his men had accumulated in Hispaniola. When he died he was still convinced that his journeys had been along the east coast of Asia. According to a study, published in February 2007, by Antonio Rodriguez Cuartero, Department of Internal Medicine of the University of Granada, he died of a heart attack caused by Reiter's Syndrome (also called reactive arthritis). According to his personal diaries and notes by contemporaries, the symptoms of this illness (burning pain during urination, pain and swelling of the knees, and conjunctivitis of the eyes) were clearly visible in his last three years.[28]

His remains were first buried in Valladolid and then at the monastery of La Cartuja in Seville (southern Spain), by the will of his son Diego, who had been governor of Hispaniola. Then in 1542, his remains were transferred to Santo Domingo, in eastern Hispaniola. In 1795, the French took over Hispaniola, and his remains were moved to Havana, Cuba. After Cuba became independent following the Spanish-American War in 1898, his remains were moved back to the Cathedral of Seville in Spain, where they were placed on an elaborate catafalque. However, a lead box bearing an inscription identifying "Don Christopher Columbus" and containing fragments of bone and a bullet was discovered at Santo Domingo in 1877.

To lay to rest claims that the wrong relics were moved to Havana and that the remains of Columbus were left buried in the cathedral of Santo Domingo, DNA samples were taken in June 2003 (History Today August 2003). The results are not definitively conclusive. Initial observations suggested that the bones did not appear to belong to somebody with the physique or age at death associated with Columbus.[29] DNA extraction proved difficult; only a few limited fragments of mitochondrial DNA could be isolated. However, such as they are, these do appear to match corresponding DNA from Columbus's brother, giving support to the idea that the two had the same mother and that the body therefore may be that of Columbus.[30][31] The authorities in Santo Domingo have not allowed the remains there to be exhumed, so it is unknown if any of those remains could be from Columbus's body.

Legacy

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2006) |

| This article or section deals primarily with the United States and does not represent a worldwide view of the subject. Please improve this article or discuss the issue on the talk page. |

Amerigo Vespucci's travel journals, published 1502-4, convinced Martin Waldseemüller that the discovered place was not India, as Columbus always believed, but a new continent, and in 1507, a year after Columbus' death, Waldseemüller published a world map calling the new continent America from Vespucci's Latinized name "Americus". Though he never set foot in what today is the United States, Columbus is sometimes viewed as a hero in that country.

Columbus ascendant

The nascent countries of the New World, particularly the newly independent United States, seemed to need a historical narrative to give them roots. This narrative was supplied in part by Washington Irving in 1828 with The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, which may be the true source of much of the associations held about the explorer.

Historically, the British had downplayed Columbus and emphasized the role of John Cabot as a pioneering explorer. But, for the emerging United States, Cabot made a poor national hero. Veneration of Columbus in America dates back to colonial times. America itself was sometimes referred to as Columbia. The use of Columbus as a founding figure of New World nations and the use of the word Columbia spread rapidly after the American Revolution. During the last two decades of the 18th century the name "Columbia" was given to the federal capital District of Columbia, South Carolina's new capital city, Columbia, South Carolina, the Columbia River, and numerous other places. Attempts to rename the United States "Columbia" failed, but Columbia became a female national personification of America, similar to the male Uncle Sam. Outside the United States the name was used in 1819 for the Republic of Colombia, a precursor of the modern nation of Colombia.

Hero worship of Columbus perhaps reached a zenith around 1892 when the 400th anniversary of his first arrival in the Americas occurred. Monuments to Columbus like the Columbian Exposition in Chicago were erected throughout the United States and Latin America extolling him. Numerous cities, towns, counties, and streets have been named after him, including the capital cities of two U.S. states (Columbus, Ohio and Columbia, South Carolina).

The story that Columbus thought the world was round while his contemporaries believed in a flat earth was often repeated despite the fact that the real issue was the size of the Earth rather than its roundness.[32] (In fact even Aristotle, a key Classical figure in the Church doctrine of the day, had argued that the Earth was a globe,[33][34] and Columbus's failure to reach China would have meant that, had he been trying to prove the world was round, he actually would have failed). This tale was used to show that Columbus was enlightened and forward looking.[citation needed]

The admiration of Columbus was particularly embraced by some members of the Italian American, Hispanic, and Catholic communities. These groups point to Columbus as one of their own to show that Mediterranean Catholics could and did make great contributions to the U.S. The modern vilification of Columbus is seen by his supporters as being politically motivated.[citation needed]

In 1909, descendants of Columbus undertook to dismantle the Columbus family chapel in Spain and move it to a site near State College, Pennsylvania, where it may now be visited by the public. At the museum associated with the chapel, there are a number of Columbus relics worthy of note, including the armchair which the "Admiral of the Ocean Sea" used at his chart table.

Modern day

- Culpability is sometimes placed on contemporary governments and their citizens for the hardship suffered by Native Americans during the time of Christopher Columbus. Columbus myths and celebrations are generally a positive affair, making less room for this concept in history books.

- The Spanish colonization of the Americas, and the subsequent effects on the native peoples, were dramatized in the 1992 feature film 1492: Conquest of Paradise to commemorate the 500th anniversary of his landing in the Americas. *In 2003, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez urged Native American Latin Americans to not celebrate the Columbus Day holiday. Chavez blamed Columbus for leading the way in the mass genocide of the Native Americans by the Spanish.[35]

- Christopher Columbus was strongly criticised[2] in a song by Jamaican artiste Burning Spear titled 'A Damn Blasted Liar.' The controversial song opened a strong opinionated debate across much of the Caribbean region on the effects that Christopher Columbus and his leadership had on the region's native peoples.[3]

- In the movie National Treasure Columbus is portrayed in the movie a being a Freemason, secretly taking the hidden treasure of the Templars to the Americas. However given the extreme secrecy of the order it is highly unlikely to prove that Columbus was a mason.

Notes

- ^ a b Encyclopedia Britannica, 1993 ed., Vol. 16, pp. 605ff / Morison, Christopher Columbus, 1955 ed., pp. 14ff

- ^ http://www.archivi.beniculturali.it/ASGE/asge.htm (In Italian)

- ^ uth G. Durlacher-Wolper: Christophoros Columbus: A Byzantine Prince from Chios, Greece. The New World Museum, San Salvador, Bahamas. 1982.

- ^ Prof. José Lorente, Prof. University of Granada in "Secrets from the Grave" (Discovery Channel, 2004)

- ^ Amy Harmon, Seeking Columbus’s Origins, With a Swab, New York Times, October 8, 2007.

- ^ (Portuguese) Rosa, Manuel, "O Mistério Colombo Revelado", pp. 157-166, Lisbon, 2006

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Marco Polo et le Livre des Merveilles", ISBN 9782354040079 p.37

- ^ Boller, Paul F (1995). Not So!:Popular Myths about America from Columbus to Clinton. ISBN 9780195091861.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton 1991. Inventing the Flat Earth. Columbus and modern historians, Praeger, New York, Westport, London 1991;

Zinn, Howard 1980. A People's History of the United States, HarperCollins 2001. p.2 - ^ Sagan, Carl. Cosmos; the mean circumference of the Earth is 40,041.47 km.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: The Life of Christopher Columbus Boston, 1942

- ^ Sagan, Carl. Cosmos; the mean circumference of the Earth is 40,041.47 km.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: The Life of Christopher Columbus Boston, 1942

- ^ Durant, Will "The Story of Civilization" vol. vi, "The Reformation". Chapter XIII, page 260.

- ^ Mark McDonald, "Ferdinand Columbus, Renaissance Collector (1488-1539)", 2005, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714126449

- ^ a b Clements R. Markham, ed. The Journal of Christopher Columbus (During His First Voyage). ASIN B000I1OMXM.

- ^ a b Kan, Michael. "Columbus Day sparks debate over explorer's legacy", The Michigan Daily, 2004-10-12.

- ^ Phillips, Jr., William D. & Carla Rahn Phillips (1992). The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. ISBN 9780521350976.

- ^ Cólón, Cristóbal, Michel de Cúneo y otros (1982). Cronistas de Indias: antología, Buenos Aires: Colihue ISBN 950-581-020-2

- ^ http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/10/17/world/main2098785.shtml

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot,Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, Boston, 1942, page 617.

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison, Christopher Columbus, Mariner, 1955, pp. 184-92.

- ^ Giles Tremlett. "Lost document reveals Columbus as tyrant of the Caribbean", The Guardian, 2006-08-07. Retrieved on 2006-10-10. (English)

- ^ Bobadilla's 48-page report—derived from the testimonies of 23 people who had seen or heard about the treatment meted out by Columbus and his brothers—had originally been lost for centuries, but was rediscovered in 2005 in the Spanish archives in Valladolid. It contained an account of Columbus' seven-year reign as the first Governor of the Indies.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot "Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus" page 576, Boston, 1942

- ^ http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/10/17/world/main2098785.shtml

- ^ Cause of the death of Colombus (in Spanish)

- ^ Giles Tremlett, Young bones lay Columbus myth to rest, The Guardian, August 11, 2004

- ^ Lorenzi, Rossella. "DNA Suggests Columbus Remains in Spain", Discovery News, October 6, 2004. Retrieved on 2006-10-11. (English)

- ^ DNA verifies Columbus’ remains in Spain, Associated Press, 19 May 2006

- ^ Round Earth and Christopher Columbus

- ^ Aristotle and the round Earth.

- ^ Compare also book 1, question 1, article 1 of Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologica, where the roundness of the Earth is given as a standard example of a well-known scientific truth.

- ^ Columbus 'sparked a genocide'. BBC News (October 12, 2003). Retrieved on 2006-10-21.

References

- Cohen, J.M. (1969) The Four Voyages of Christopher Columbus: Being His Own Log-Book, Letters and Dispatches with Connecting Narrative Drawn from the Life of the Admiral by His Son Hernando Colon and Others. London UK: Penguin Classics.

- Cook, Sherburn and Woodrow Borah (1971) Essays in Population History, Volume I. Berkeley CA: University of California Press

- Crosby, A. W. (1987) The Columbian Voyages: the Columbian Exchange, and their Historians. Washington, DC: American Historical Association.

- Friedman, Thomas (2005) The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux.

- Hart, Michael H. (1992) The 100. Seacaucus NJ: Carol Publishing Group.

- Keen, Benjamin (1978) The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by his Son Ferdinand, Westport CT: Greenwood Press.

- Lowen, James. "Lies My Teacher Told Me".

- Nelson, Diane M. (1999) A Finger in the Wound: Body Politics in Quincentennial Guatemala. Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1942.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot, Christopher Columbus, Mariner, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1955.

- Phillips, W. D. and C. R. Phillips (1992) The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Turner, Jack (2004) Spice: The History of a Temptation. New York: Random House.

- Wilford, John Noble (1991) The Mysterious History of Columbus: An Exploration of the Man, the Myth, the Legacy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Rosa, Manuel DaSilva (2006) O Mistério Colombo Revelado. Lisbon: Ésquilo.

See also

- 1492: Conquest of Paradise, a 1992 biopic film by Ridley Scott

- Christopher Columbus, a 1949 film starring Fredric March as Columbus

- Bartolomeo Columbus

- Columbus Day

- Colombia, South American country named in honor of Christopher Columbus

- Fernando Colón

- Guanahani (a discussion of candidates for site of first landing)

- Knights of Columbus

- List of places named for Christopher Columbus

- Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

External links

- The Letter of Columbus to Luis de Sant Angel Announcing His Discovery

- Podcasts and audio about Columbus

- Columbus Navigation

- Educational Lesson on Columbus Voyages Use surface current data to track Columbus' voyage.

- Reconstructed portrait of Christopher Columbus in a contemporary style.

- Unmasking Columbus

- Works by Christopher Columbus at Project Gutenberg

- The Eclipse That Saved Columbus Science News 7 October 2006

- Christopher Columbus and the Indians By Howard Zinn, from A People's History of the United States

- Colombo Revelado A new biography showing the lack of proof and invented facts about a Genoese turning the known history upside down.

- The Catalan Columbus — Theory of the Catalan origin of (Joan) Cristòfor Colom (i Bertran)

- Christopher Columbus 1911 Britannica article

- Fox News: Desperate New World Settlers Stole Christopher Columbus' Silver

- IMDB

- Animated Hero Classics: Christopher Columbus (1991) at the Internet Movie Database

- 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992) at the Internet Movie Database

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Columbus, Christopher |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Cristoforo Colombo, Cristóbal Colón |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | navigator and an admiral for the Crown of Castile |

| DATE OF BIRTH | c. 1451 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Genoa |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 20, 1506 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Valladolid, Spain |

Categories: All articles with unsourced statements | Articles with unsourced statements since November 2007 | Articles with unsourced statements since January 2008 | Articles with unsourced statements since December 2007 | Articles with unsourced statements since February 2007 | Articles with unsourced statements since October 2007 | Articles with unsourced statements since March 2007 | Articles needing additional references from December 2006 | Articles with limited geographic scope | USA-centric | Italian explorers | Explorers of Central America | Age of Discovery | People from Genoa (city) | 1451 births | 1506 deaths

- Log in to post comments

1776AD Declaration of Independence: Government By Consent of the People, by the People, for the People

" ... and they shall reign forever and ever ... "

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Declaration_of_Independence

United States Declaration of Independence

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| United States Declaration of Independence | |

The Declaration of Independence

|

|

| Created | July 4, 1776 |

| Location | National Archives and Records Administration |

| Authors |

Thomas Jefferson John Adams Benjamin Franklin |

| Signers | Continental Congress |

| Purpose | Declare independence from Great Britain |

The United States Declaration of Independence was an act of the Second Continental Congress, adopted on July 4, 1776, which declared that the Thirteen Colonies in North America were "Free and Independent States" and that "all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved." The document, formally entitled The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United States of America,[1] explained the justifications for separation from the British crown, and was an expansion of Richard Henry Lee's Resolution (passed by Congress on July 2), which first proclaimed independence. An engrossed copy of the Declaration was signed by most of the delegates on August 2 and is now on display in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C.

The Declaration is considered to be the founding document of the United States of America, where July 4 is celebrated as Independence Day and the nation's birthday. At the time the Declaration was issued, the American colonies were "united" in declaring their independence from Great Britain. John Hancock, as the elected President of Congress, was the only person to sign the Declaration of Independence on July 4th. It was not until the following month on August 2nd that the remaining 55 other delegates began to sign the document.

US President Abraham Lincoln succinctly explained the central importance of the Declaration to American history in his Gettysburg Address of 1863:

- "Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal."

Contents[hide] |

History

Background

As relations between Great Britain and its American colonies became increasingly strained, the Americans set up a shadow government in each colony, with a Continental Congress and Committees of Correspondence linking these shadow governments. As soon as fighting broke out in April 1775, these shadow governments took control of each colony and ousted all the royal officials. Sentiment for outright independence grew rapidly in response to British actions; the options were clarified by Thomas Paine's pamphlet Common Sense, released in January 1776.

Draft and adoption

In June of 1776, a committee of the Second Continental Congress consisting of John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut (the "Committee of Five") was formed to draft a suitable declaration to frame this resolution. The committee decided that Jefferson would write the draft, which he showed to Franklin and Adams. Prior to deciding on Jefferson, both Adams and Franklin turned down the offer, citing that if they wrote it people would read it with a biased eye. Franklin himself made at least 48 corrections. Jefferson then produced another copy incorporating these changes, and the committee presented this copy to the Continental Congress on June 28, 1776.

A formal declaration for independence was delayed on July 2, 1776, pursuant to the "Lee Resolution" presented by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia on June 7, 1776, which read (in part): '"Resolved: That these united Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."'

The full Declaration was reworked somewhat in general session of the Continental Congress. Congress, meeting in Independence Hall in Philadelphia, finished revising Jefferson's draft statement on July 4, approved it, and sent it to a printer. At the signing, Benjamin Franklin is quoted as having replied to a comment by Hancock that they must all hang together: "Yes, we must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately,"[2] a play on words indicating that failure to stay united and succeed would lead to being tried and executed, individually, for treason.

Analysis

Influences

The Declaration of Independence was also strongly influenced by Thomas Paine's pamphlet, Common Sense and from the Enlightenment. It even borrowed one of the sentences; the line "life, liberty, and the pursuit of property" from Common Sense was changed to "among these are Life Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness". "The pursuit of Happiness" was also a line from Common Sense, that was used in a different part of the pamphlet. This is not particularly plagiarism, as Sense was very influential to Jefferson and the other Founding Fathers, as well as most Americans as a whole.

Stephen Lucas, who had earlier made detailed comments on this topic,[3] suggested in 1998 that Jefferson was also inspired by the Dutch Oath of Abjuration when he wrote the Declaration. Both documents show tremendous similarities, one of the most notable being the principle of a people's right to denounce and overthrow their leaders should they fail to respect the people's laws and traditions.[4]

Philosophical background

The Preamble of the Declaration is influenced by the spirit of republicanism, which was used as the basic framework for liberty.[5] In addition, it reflects the concepts of natural law, and self-determination. Ideas and even some of the phrasing were taken directly from the writings of English philosopher John Locke. Thomas Paine's Common Sense had been widely read and provided a simple, clear case for independence that many found compelling. According to Jefferson, the purpose of the Declaration was "not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of . . . but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take."

International law

Armitage (2002) examines the Declaration of Independence in the context of late-18th century international law and argues its legitimacy derived more from its broad appeal to diverse audiences than from its comportment with extant principles of international relations. He analyzes the Declaration's structure and fundamental arguments, concluding that its partial reliance on an individual natural rights political discourse seemed outdated, if not obsolete, in an international arena where positivist jurisprudential philosophy was increasingly becoming the preferred referent. Armitage highlights the consequent apprehension felt by leading American statesmen during 1776-79, including John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, as the manifesto circulated throughout Europe receiving an ambiguous reception at best. Nonetheless, with the de jure acceptance of US independence in the Treaty of Paris (1783), arguments regarding the legal foundations of the Declaration of Independence became irrelevant, as its objective and its success as a document written to appeal to internal as well as foreign audiences became more widely recognized and admired.

Practical effects

As a proclamation, the Declaration was used as a propaganda tool, in which the Americans tried to establish clear reasons for their rebellion that might persuade reluctant colonists to join them and establish their just cause to foreign governments that might lend them aid. The Declaration also served to unite the members of the Continental Congress. The Declaration of Independence was also used as a foreign policy announcement; since the United States were now separate and independent nations, the war was escalated from a civil war to a war of independence, and therefore foreign nations who were enemies of Great Britain were free to intervene, like the French. One in five colonists[6](calling themselves loyalists or Tories) refused to accept the Declaration and continued to profess their allegiance to the British monarchy, with over 700 of them signing their own "declaration" in a pub on Wall Street.[6] Many were upper class landowners and businessmen who felt the new republic would strip them of their land rights and social class.[citation needed]

The Declaration published outside the Thirteen Colonies

The Declaration of Independence was first published in full outside North America by the Belfast Newsletter on the 23rd of August, 1776.[7] A copy of the document was being transported to London via ship when bad weather forced the vessel to port at Derry. The document was then carried on horseback to Belfast for the continuation of its voyage to England, whereupon copy was made for the Belfast newspaper.[8][9]

The first edition of the Declaration of Independence was reprinted at London in the August 1776 issue of The Gentleman's Magazine. The Gentleman's Magazine had been following American issues for many years, and its editors (Edward Cave and, subsequently, David Henry) were close to Benjamin Franklin in particular, publishing several of his writings on electricity. The Declaration itself was followed in the September issue by "Thoughts on the late Declaration of the American Congress", signed only "An Englishman". The author identified certain absurdities (as he saw them) contained in the now famous words of the preamble. Most notably, he pointed out the document's inconsistency with the fact that slavery and government was still being practiced in America (emphasized in the following excerpt):

We hold (they say) these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal. In what are they created equal? Is it in size, understanding, figure, moral or civil accomplishments, or situation of life? Every plough-man knows that they are not created equal in any of these....That every man hath an unalienable right to liberty; and here the words, as it happens, are not nonsense, but they are not true: slaves there are in America, and where there are slaves, there liberty is alienated. If the Creator hath endowed man with an unalienable right to liberty, no reason in the world will justify the abridgement of that liberty, and a man hath a right to do everything that he thinks proper without controul or restraint; and upon the same principle, there can be no such things as servants, subjects, or government of any kind whatsoever. In a word, every law that hath been in the world since the formation of Adam, gives the lie to this self-evident truth, (as they are pleased to term it) ; because every law, divine or human, that is or hath been in the world, is an abridgement of man's liberty. (The Gentleman's Magazine, vol. 46, pp. 403–404)

Distribution and copies

After its adoption by Congress on July 4, a handwritten draft signed by the President of Congress John Hancock and the Secretary Charles Thomson was then sent a few blocks away to the printing shop of John Dunlap. Through the night between 150 and 200 copies were made, now known as "Dunlap broadsides". The first public reading of the document was by John Nixon in the yard of Independence Hall on July 8.[10] One was sent to George Washington on July 6, who had it read to his troops in New York on July 9. A copy reached London on August 10.[citation needed] The 25 Dunlap broadsides still known to exist are the oldest surviving copies of the document. The original handwritten copy has not survived.

On July 19, Congress ordered a copy be "engrossed" (hand written in fair script on parchment by an expert penman) for the delegates to sign. This engrossed copy was produced by Timothy Matlack, assistant to the secretary of Congress. Most of the delegates signed it on August 2, 1776, in geographic order of their colonies from north to south, though some delegates were not present and had to sign later. Late signers were Elbridge Gerry, Oliver Wolcott, Lewis Morris, Thomas McKean, and Matthew Thornton (who, because of a lack of space, was unable to place his signature on the top right of the signing area with the other New Hampshire delegates, William Whipple and Josiah Bartlett, and had to place his signature on the lower right). As new delegates joined the congress, they were also allowed to sign. A total of 56 delegates eventually signed (see Category:Signers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence). This engrossed copy is now on display at the National Archives.

Three delegates never signed. Robert R. Livingston, a member of the original drafting committee, was present for the vote on July 2 but returned to New York before the August 2 signing. John Dickinson, a member of the Continental Congress from Pennsylvania, was against separation from Great Britain and labored to change the language of the Declaration of Independence to leave open the possibility of a reconciliation with Great Britain. Thomas Lynch voted for the Declaration but could not sign it because of illness.

On January 18, 1777, the Continental Congress ordered that the declaration be more widely distributed. The second printing was made by Mary Katharine Goddard. The first printing had included only the names John Hancock and Charles Thomson. Goddard's printing was the first to list all signatories.

In 1823, printer William J. Stone was commissioned by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams to create an engraving [1] of the document essentially identical to the original. Stone's copy was made using a wet-ink transfer process, where the surface of the document was moistened, and some of the original ink transferred to the surface of a copper plate which was then etched so that copies could be run off the plate on a press[11]. Because of poor conservation of the 1776 document through the 19th century, Stone's engraving, rather than the original, has become the basis of most modern reproductions[12]

The first German translation of the Declaration was published July 6-8, 1776, as a broadside in unfolded form by the printing press of Steiner & Cist of Philadelphia.[13]

Gustafson (2004) traces the paths taken by the original manuscript copies of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights prior to being placed permanently in the National Archives. From 1776 to 1921 the Declaration moved from one city to another and to different public buildings until placed in the Department of State library. The Constitution was never exhibited, and the Bill of Rights' provenance up to 1938 is largely unknown. From 1921 to 1952 the Declaration and the Constitution were at the Library of Congress, and the National Archives held the Bill of Rights.

In 1952, the librarian of Congress and the US archivist agreed on moving the Declaration and the Constitution to the National Archives. Since 1953 the three documents have been called the Charters of Freedom. Encased in 1951, by the early 1980s deterioration threatened the documents. In 2001, using the latest in preservation technology, conservators treated the documents and re-encased them in encasements made of titanium and aluminum, filled with inert Argon gas. They were put on display again with the opening of the remodeled National Archives Rotunda in 2003.

Annotated text of the Declaration

The declaration is not divided into formal sections; but it is often discussed as consisting of five parts: Introduction, the Preamble, the Indictment of George III, the Denunciation of the British people, and the Conclusion.[14]

|

Introduction Asserts as a matter of Natural Law the ability of a people to assume political independence; acknowledges that the grounds for such independence must be reasonable, and therefore explicable, and ought to be explained. |

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. |

|

Preamble Outlines a general philosophy of government that justifies revolution when government harms natural rights.[14] |

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. |

|

Indictment A bill of particulars documenting the king's "repeated injuries and usurpations" of the Americans' rights and liberties.[14] |

Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness of his invasions on the rights of the people. He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected, whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance. He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people. |

|

Denunciation This section essentially finished the case for independence. The conditions that justified revolution have been shown.[14] Many Americans still felt a kinship with the people of England, and had appealed in vain to the prominent among them, as well as to Parliament, to convince the King to relax his more objectionable policies toward the colonies.[15] This section represents the Framers' disappointment that their attempts were unsuccessful. |

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends. |

|

Conclusion The signers assert that there exist conditions under which people must change their government, that the British have produced such conditions, and by necessity the colonies must throw off political ties with the British Crown and become independent states. The conclusion contains, at its core, the Lee Resolution that had been passed on July 2. |

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor. |

|