354-430AD Augustine: "1000 Years" Millennium started in 1st Century: (either 1AD or 70AD)

"Another important division of historical interpreters is into Post-Millennarians and Pre-Millennarians, according as the millennium predicted in Revelation 20 is regarded as part or future. Augustin committed the radical error of dating the millennium from the time of the Apocalypse or the beginning of the Christian era (although the seer mentioned it near the end of his book), and his view had great influence; hence the wide expectation of the end of the world at the close of the first millennium of the Christian church. Other post-millennarian interpreters date the millennium from the triumph of Christianity over paganism in Rome at the accession of Constantine the Great (311);"

(Excerpted from Schaff's History of the Church, PC Study Bible formatted electronic database Copyright © 1999, 2003, 2005, 2006 by Biblesoft, Inc. All rights reserved.)

["Radical error" or not is open to debate. (Philip Schaff went on to embrace historical Preterism, noting his own change of doctrinal position in later editions of this work.) But without argument, St. Augustin dated Rev 20:1-10’s “1000 Years” from the time of the writing of Revelation ("The Apocalypse" in Latin) or the beginning of the Christian era to the end of the first millennium of the Christian church. This view was so widely held during the Middle Age that there was wide expectation of the end of the world at 1000AD, the close of the first millennium of the Christian church. I agree with St. Augustin, (354-430AD), that he was living near the middle of Rev 20:1-10's "1000 years." ~jwr

MILLENNIUM : Latin MILLE, thousand + Latin ANNUS, year

http://www.amazon.com/gp/reader/0140448942/ref=sib_dp_pop_bc?ie=UTF8&p=S0X0#reader-link

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustine_of_Hippo

Augustine of Hippo

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Saint Augustine of Hippo | |

|---|---|

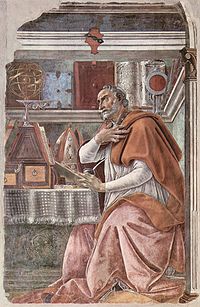

Augustine as depicted by Sandro Botticelli, c. 1480 | |

| Bishop and Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | November 13, 354, Tagaste, Algeria |

| Died | August 28, 430 (aged 75), Hippo Regius |

| Venerated in | most Christian groups |

| Major shrine | San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro, Pavia, Italy |

| Feast | August 28 (W), June 15 (E) |

| Attributes | child; dove; pen; shell, pierced heart |

| Patronage | brewers; printers; sore eyes; theologians |

Aurelius Augustinus, Augustine of Hippo, or Saint Augustine (November 13, 354 – August 28, 430) was a philosopher and theologian, and was bishop of the North African city of Hippo Regius for the last third of his life. Augustine is one of the most important figures in the development of Western Christianity, and is considered to be one of the church fathers. He framed the concepts of original sin and just war.

In Roman Catholicism and the Anglican Communion, he is a saint and pre-eminent Doctor of the Church, and the patron of the Augustinian religious order. Many Protestants, especially Calvinists, consider him to be one of the theological fathers of Reformation teaching on salvation and grace. In the Eastern Orthodox Church he is a saint, and his feast day is celebrated annually on June 15, though a minority are of the opinion that he is a heretic, primarily because of his statements concerning what became known as the filioque clause.[1] Among the Orthodox he is called Blessed Augustine, or St. Augustine the Blessed. "Blessed" here does not mean that he is less than a saint, but is a title bestowed upon him as a sign of respect.[2] The Orthodox do not remember Augustine so much for his theological speculations as for his writings on spirituality. In addition he believed in Papal supremacy. [3]

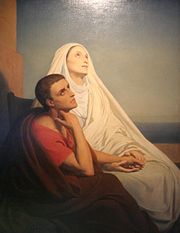

Born in present day Algeria as the eldest son of Saint Monica, he was educated in North Africa and baptized in Milan. His works—including The Confessions, which is often called the first Western autobiography—are still read around the world.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Life

Saint Augustine was of Berber descent[4] and was born in 354 A.D. in Tagaste (present-day Souk Ahras, Algeria), a provincial Roman city in North Africa.[5] At the age of 11, Augustine was sent to school at Madaurus, a small Numidian city about 19 miles south of Tagaste noted for its pagan climate. There he became very familiar with Latin literature, as well as pagan beliefs and practices.[6] In 369 and 370, he remained at home. During this period he read Cicero's dialogue Hortensius, which he described as leaving a lasting impression on him and sparking his interest in philosophy.[5] At age seventeen, through the generosity of a fellow citizen Romanianus,[5] he went to Carthage to continue his education in rhetoric. His revered mother, Monica,[7] was a Berber and a devout Catholic, and his father, Patricius, a pagan. Although raised as a Catholic, Augustine left the Church to follow the controversial Manichaean religion, much to the despair of his mother. As a youth Augustine lived a hedonistic lifestyle for a time and, in Carthage, he developed a relationship with a young woman who would be his concubine for over fifteen years. During this period he had a son, Adeodatus,[8] with the young woman. During the years 373 and 374, Augustine taught grammar at Tagaste. The following year, he moved to Carthage to conduct a school of rhetoric there, and would remain there for the next nine years.[5] Disturbed by the unruly behaviour of the students in Carthage, in 383 he moved to Rome to establish a school there, where he believed the best and brightest rhetoricians practiced. However, Augustine was disappointed with the Roman schools, which he found apathetic. Once the time came for his students to pay their fees they simply fled. Manichaean friends introduced him to the prefect of the City of Rome, Symmachus, who had been asked to provide a professor of rhetoric for the imperial court at Milan.

The young provincial won the job and headed north to take up his position in late 384. At age thirty, Augustine had won the most visible academic chair in the Latin world, at a time when such posts gave ready access to political careers. However, he felt the tensions of life at an imperial court, lamenting one day as he rode in his carriage to deliver a grand speech before the emperor, that a drunken beggar he passed on the street had a less careworn existence than he did.

It was at Milan that Augustine's life changed. While still at Carthage, he had begun to move away from Manichaeism, in part because of a disappointing meeting with a key exponent of Manichaean theology. In Rome, he is reported to have completely turned away from Manichaeanism, and instead embraced the skepticism of the New Academy movement. At Milan, his mother Monica pressured him to become a Catholic. Augustine's own studies in Neoplatonism were also leading him in this direction, and his friend Simplicianus urged him that way as well.[5] But it was the bishop of Milan, Ambrose, who had most influence over Augustine. Ambrose was a master of rhetoric like Augustine himself, but older and more experienced.

Augustine's mother had followed him to Milan and he allowed her to arrange a society marriage, for which he abandoned his concubine (however he had to wait two years until his fiancée came of age; he promptly took up in the meantime with another woman). It was during this period that he uttered his famous prayer, "Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet" [da mihi castitatem et continentiam, sed noli modo] (Conf., VIII. vii (17)).

In the summer of 386, after having read an account of the life of Saint Anthony of the Desert which greatly inspired him, Augustine underwent a profound personal crisis and decided to convert to Catholic Christianity, abandon his career in rhetoric, quit his teaching position in Milan, give up any ideas of marriage, and devote himself entirely to serving God and the practices of priesthood, which included celibacy. Key to this conversion was the voice of an unseen child he heard while in his garden in Milan telling him in a sing-song voice to "tolle lege" ("take up and read") the Bible, at which point he opened the Bible at random and fell upon the Epistle to the Romans 13:13, which reads: "Let us walk honestly, as in the day; not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying" (KJV). He would detail his spiritual journey in his famous Confessions, which became a classic of both Christian theology and world literature. Ambrose baptized Augustine, along with his son, Adeodatus, on Easter Vigil in 387 in Milan, and soon thereafter in 388 he returned to Africa.[5] On his way back to Africa his mother died, as did his son soon after, leaving him alone in the world without family.

Upon his return to north Africa he sold his patrimony and gave the money to the poor. The only thing he kept was the family house, which he converted into a monastic foundation for himself and a group of friends.[5] In 391 he was ordained a priest in Hippo Regius (now Annaba, in Algeria). He became a famous preacher (more than 350 preserved sermons are believed to be authentic), and was noted for combating the Manichaean religion, to which he had formerly adhered.

In 396 he was made coadjutor bishop of Hippo (assistant with the right of succession on the death of the current bishop), and became full bishop shortly thereafter. He remained in this position at Hippo until his death in 430. Augustine worked tirelessly in trying to convince the people of Hippo, who were diverse racial and religious group, to convert to the Catholic faith. He left his monastery, but continued to lead a monastic life in the episcopal residence. He left a Rule (Latin, Regula) for his monastery that has led him to be designated the "patron saint of Regular Clergy", that is, Clergy who live by a monastic rule.

Augustine died on August 28, 430 during the siege of Hippo by the Vandals. On his death bed he was read the Enneads of Plotinus. He is said to have encouraged its citizens to resist the attacks, primarily on the grounds that the Vandals adhered to Arianism, a heterodox branch of Christianity. It is also said that he died just as the Vandals were tearing down the city walls of Hippo.

After conquering the city, the Vandals destroyed all of it but Augustine's cathedral and library, which they left untouched. Tradition indicates that his body was later moved to Pavia, where it is said to remain to this day.[5]

[edit] Works

Augustine was one of the most prolific Latin authors, and the list of his works consists of more than a hundred separate titles.[9] They include apologetic works against the heresies of the Arians, Donatists, Manichaeans and Pelagians, texts on Christian doctrine, notably De doctrina Christiana (On Christian Doctrine), exegetical works such as commentaries on Genesis, the Psalms and Paul's Letter to the Romans, many sermons and letters, and the Retractationes (Retractions), a review of his earlier works which he wrote near the end of his life. Apart from those, Augustine is probably best known for his Confessiones (Confessions), which is a personal account of his earlier life, and for De civitate Dei (The City of God, consisting of 22 books), which he wrote to restore the confidence of his fellow Christians, which was badly shaken by the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410. His 'On the Trinity' (De Trinitate), in which he developed what has become known as the 'psychological analogy' of the Trinity, is also among his masterpieces, and arguably one of the greatest theological works of all time.

[edit] Influence as a theologian and thinker

Augustine remains a central figure, both within Christianity and in the history of Western thought, and is considered by modern historian Thomas Cahill to be the first medieval man and the last classical man.[10] In both his philosophical and theological reasoning, he was greatly influenced by Stoicism, Platonism and Neo-platonism, particularly by the work of Plotinus, author of the Enneads, probably through the mediation of Porphyry and Victorinus (as Pierre Hadot has argued). His generally favorable view of Neoplatonic thought contributed to the "baptism" of Greek thought and its entrance into the Christian and subsequently the European intellectual tradition. His early and influential writing on the human will, a central topic in ethics, would become a focus for later philosophers such as Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. In addition, Augustine was influenced by the works of Virgil (known for his teaching on language), Cicero (known for his teaching on argument), and Aristotle (particularly his Rhetoric and Poetics).

Augustine's concept of original sin was expounded in his works against the Pelagians. However, Eastern Orthodox theologians, while they believe all humans were damaged by the original sin of Adam and Eve, have key disputes with Augustine about this doctrine, and as such this is viewed as a key source of division between East and West. His writings helped formulate the theory of the just war. He also advocated the use of force against the Donatists, asking "Why ... should not the Church use force in compelling her lost sons to return, if the lost sons compelled others to their destruction?" (The Correction of the Donatists, 22–24). St. Thomas Aquinas took much from Augustine's theology while creating his own unique synthesis of Greek and Christian thought after the widespread rediscovery of the work of Aristotle. While Augustine's doctrine of divine predestination and efficacious grace would never be wholly forgotten within the Roman Catholic Church, finding eloquent expression in the works of Bernard of Clairvaux, Reformation theologians such as Martin Luther and John Calvin would look back to him as the inspiration for their avowed capturing of the Biblical Gospel. Bishop John Fisher of Rochester, a chief opponent of Luther, articulated an Augustinian view of grace and salvation consistent with Church doctrine, thus encompassing both Augustine’s soteriology and his teaching on the authority of and obedience to the Catholic Church.[11] Later, within the Roman Catholic Church, the writings of Cornelius Jansen, who claimed heavy influence from Augustine, would form the basis of the movement known as Jansenism. But what the members of the reformation at that time didn't really get into the fact that St. Augustine believed in Papal supremacy.

Augustine was canonized by popular acclaim, and later recognized as a Doctor of the Church in 1303 by Pope Boniface VIII[citation needed]. His feast day is August 28, the day on which he died. He is considered the patron saint of brewers, printers, theologians, sore eyes, and a number of cities and dioceses.

The latter part of Augustine's Confessions consists of an extended meditation on the nature of time. Even the agnostic philosopher Bertrand Russell was impressed by this. He wrote, "a very admirable relativistic theory of time. ... It contains a better and clearer statement than Kant's of the subjective theory of time - a theory which, since Kant, has been widely accepted among philosophers."[12] Catholic theologians generally subscribe to Augustine's belief that God exists outside of time in the "eternal present"; that time only exists within the created universe because only in space is time discernible through motion and change. His meditations on the nature of time are closely linked to his consideration of the human ability of memory. Frances Yates in her 1966 study, The Art of Memory argues that a brief passage of the Confessions, X.8.12, in which Augustine writes of walking up a flight of stairs and entering the vast fields of memory [13] clearly indicates that the ancient Romans were aware of how to use explicit spatial and architectural metaphors as a mnemonic technique for organizing large amounts of information. According to Leo Ruickbie, Augustine's arguments against magic, differentiating it from miracle, were crucial in the early Church's fight against paganism and became a central thesis in the later denunciation of witches and witchcraft. According to Professor Deepak Lal, Augustine's vision of the heavenly city has influenced the secular projects and traditions of the Enlightenment, Marxism, Freudianism and Eco-fundamentalism[citation needed].

[edit] Influential quotations from Augustine's writings

- "Give what Thou dost command, and command what Thou wilt." ("Da quod jubes, et jube quod vis," Confessions X, xxix, 40)

- "Thou madest us for Thyself, and our heart is restless until it repose in Thee." (Confessions I, i, 1)

- "Love the sinner and hate the sin" (Cum dilectione hominum et odio vitiorum) (Opera Omnia, vol II. col. 962, letter 211.), literally "With love for mankind and hatred of sins "[14]

- "Excess [i.e., 'extravagant self-indulgence, riotous living'] is the enemy of God" (Luxuria est inimica Dei.)

- "Heart speaks to heart" (Cor ad cor loquitur)[15]

- "Nothing conquers except truth and the victory of truth is love" (Victoria veritatis est caritas}[16]

- "To sing once is to pray twice" (Qui cantat, bis orat) literally "he who sings, prays twice"[17]

- "Lord, you have seduced me and I let myself be seduced" (quoting the prophet Jeremiah 20.7-9)

- "Love, and do what you will" (Dilige et quod vis fac) Sermon on 1 John 7, 8[18]

- "Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet" (da mihi castitatem et continentiam, sed noli modo) (Conf., VIII. vii (17))

- "God, O Lord, grant me the power to overcome sin. For this is what you gave to us when you granted us free choice of will. If I choose wrongly, then I shall be justly punished for it. Is that not true, my Lord, of whom I indebted for my temporal existence? Thank you, Lord, for granting me the power to will my self not to sin.(Free Choice of the Will, Book One)"

- "Christ is the teacher within us"[19] (A paraphrase; see De Magistro - "On the Teacher" - 11:38)

- "Hear the other side" (Audi partem alteram) De Duabus Animabus, XlV ii

- "Take up [the book], and Read it" (Tolle, lege) Confessions, Book VIII, Chapter 12

- "There is no salvation outside the church" (Salus extra ecclesiam non est) (De Bapt. IV, cxvii.24)

- "To many, total abstinence is easier than perfect moderation." (Multi quidem facilius se abstinent ut non utantur, quam temperent ut bene utantur. - Lit. 'For many it is indeed easier to abstain so as not to use [married sexual relations] at all, than to control themselves so as to use them aright.') (On the Good of Marriage)

- "We make ourselves a ladder out of our vices if we trample the vices themselves underfoot." (iii. De Ascensione)

- "Hope has two beautiful daughters. Their names are anger and courage; anger at the way things are, and courage to see that they do not remain the way they are." (quoted in William Sloane Coffin, The Heart Is a Little to the Left)

[edit] Theology

[edit] Natural knowledge and biblical interpretation

Augustine took the view that the Biblical text should not be interpreted literally if it contradicts what we know from science and our God-given reason. In "The Literal Interpretation of Genesis" (early 5th century, AD), St. Augustine wrote:

It not infrequently happens that something about the earth, about the sky, about other elements of this world, about the motion and rotation or even the magnitude and distances of the stars, about definite eclipses of the sun and moon, about the passage of years and seasons, about the nature of animals, of fruits, of stones, and of other such things, may be known with the greatest certainty by reasoning or by experience, even by one who is not a Christian. It is too disgraceful and ruinous, though, and greatly to be avoided, that he [the non-Christian] should hear a Christian speaking so idiotically on these matters, and as if in accord with Christian writings, that he might say that he could scarcely keep from laughing when he saw how totally in error they are. In view of this and in keeping it in mind constantly while dealing with the book of Genesis, I have, insofar as I was able, explained in detail and set forth for consideration the meanings of obscure passages, taking care not to affirm rashly some one meaning to the prejudice of another and perhaps better explanation.

– The Literal Interpretation of Genesis 1:19–20, Chapt. 19 [AD 408]

With the scriptures it is a matter of treating about the faith. For that reason, as I have noted repeatedly, if anyone, not understanding the mode of divine eloquence, should find something about these matters [about the physical universe] in our books, or hear of the same from those books, of such a kind that it seems to be at variance with the perceptions of his own rational faculties, let him believe that these other things are in no way necessary to the admonitions or accounts or predictions of the scriptures. In short, it must be said that our authors knew the truth about the nature of the skies, but it was not the intention of the Spirit of God, who spoke through them, to teach men anything that would not be of use to them for their salvation.

– ibid, 2:9

A more clear distinction between "metaphorical" and "literal" in literary texts arose with the rise of the Scientific Revolution, although its source could be found in earlier writings, such as those of Herodotus (5th century BC). It was even considered heretical to interpret the Bible literally at times (cf. Origen, St. Jerome).[citation needed]

[edit] Creation

- See also: Allegorical interpretations of Genesis

In "The Literal Interpretation of Genesis" Augustine took the view that everything in the universe was created simultaneously by God, and not in seven calendar days like a plain account of Genesis would require. He argued that the six-day structure of creation presented in the book of Genesis represents a logical framework, rather than the passage of time in a physical way - it would bear a spiritual, rather than physical, meaning, which is no less literal. Augustine also doesn’t envisage original sin as originating structural changes in the universe, and even suggests that the bodies of Adam and Eve were already created mortal before the Fall. Apart from his specific views, Augustine recognizes that the interpretation of the creation story is difficult, and remarks that we should be willing to change our mind about it as new information comes up. [4]

In "The City of God", Augustine also defended what would be called today as young Earth creationism. In the specific passage, Augustine rejected both the immortality of the human race proposed by pagans, and contemporary ideas of ages (such as those of certain Greeks and Egyptians) that differed from the Church's sacred writings:

Let us, then, omit the conjectures of men who know not what they say, when they speak of the nature and origin of the human race. For some hold the same opinion regarding men that they hold regarding the world itself, that they have always been... They are deceived, too, by those highly mendacious documents which profess to give the history of many thousand years, though, reckoning by the sacred writings, we find that not 6000 years have yet passed.

– Augustine, Of the Falseness of the History Which Allots Many Thousand Years to the World’s Past, The City of God, Book 12: Chapt. 10 [AD 419].

[edit] Original Sin

Augustine taught that Original Sin was transmitted by concupiscence (roughly, lust), weakening the will[20] and making humanity a massa damnata[20] (mass of perdition, condemned crowd). In the struggle against Pelagianism, Augustine's teaching was confirmed by many councils, especially the Second Council of Orange.[20] The identification of concupiscence and Original Sin, however, was challenged by Anselm and condemned in 1567 by Pope Pius V.[20]

Augustine's formulation of the doctrine of original sin has substantially influenced both Catholic and Reformed (that is, Calvinist) theology. His understanding of sin and grace was developed against that of Pelagius.[21] Expositions on the topics are found in his works On Original Sin, On the Predestination of the Saints, On the Gift of Perseverance and On Nature and Grace.

Original sin, according to Augustine, consists of the guilt of Adam which all human beings inherit. As sinners, human beings are utterly depraved in nature, lack the freedom to do good, and cannot respond to the will of God without divine grace. Grace is irresistible, results in conversion, and leads to perseverance.[21] Augustine's idea of predestination rests on the assertion that God has foreordained, from eternity, those who will be saved. The number of the elect is fixed.[21] God has chosen the elect certainly and gratuitously, without any previous merit (ante merita) on their part.

The Roman Catholic Church considers Augustine's teaching to be consistent with free will.[22] He often said that any can be saved if they wish.[22] While God knows who will be saved and who won't, with no possibility that one destined to be lost will be saved, this knowledge represents God's perfect knowledge of how humans will freely choose their destinies.[22]

[edit] Ecclesiology

- See also: Ecclesiology

Augustine developed his doctrine of the chuch principally in reaction to the Donatist sect. He taught a distinction between the "church visible" and "church invisible". The former is the institutional body on earth which proclaims salvation and administers the sacraments while the latter is the invisible body of the elect, made up of genuine believers from all ages, and who are known only to God. The visible church will be made up of "wheat" and "tares", that is, good and wicked people, until the end of time. This concept countered the Donatist claim that they were the only "true" or "pure" church on earth.[21]

Augustine's ecclesiology was more fully developed in City of God. There he conceives of the church as a heavenly city or kingdom, ruled by love, which will ultimately triumph over all earthly empires which are self-indulgent and ruled by pride. Augustine followed Cyprian in teaching that the bishops of the church are the successors of the apostles.[21]

[edit] Sacramental theology

Also in reaction against the Donatists, Augustine developed a distinction between the "regularity" and "validity" of the sacraments. Regular sacraments are performed by clergy of the Catholic (that is, the legitimate) church while sacraments performed by schismatics are considered irregular. Nevertheless, the validity of the sacraments do not depend upon the holiness of the priests who perform them; therefore, irregular sacraments are still accepted as valid provided they are done in the name of Christ and in the manner prescribed by the church. On this point Augustine departs from the earlier teaching of Cyprian, who taught that converts from schismatic movements must be re-baptised.[21]

Against the Pelagians Augustine strongly stressed the importance of infant baptism. He believed that no one would be saved unless he or she had received baptism in order to be cleansed from original sin. He also maintained that unbaptized children would go to hell. It was not until the 12th century that pope Innocent III accepted the doctrine of limbo as promulgated by Peter Abelard. It was the place where the unbaptized went and suffered no pain but, as the Church maintained, being still in a state of original sin, they did not deserve Paradise, therefore they did not know happiness either. The Church of England disavowed the state of original sin in the 16th century. Non-conformist religions such as the Unitarians and the Quakers never held to the concept.

[edit] Eschatology

Augustine originally believed that Christ would establish a literal 1,000-year kingdom prior to the general resurrection (premillennialism or chiliasm) but rejected the system as carnal. He was the first theologian to systematically expound a doctrine of amillennialism, although some theologians and Christian historians believe his position was closer to that of modern postmillennialists. The mediaeval Catholic church built its system of eschatology on Augustinian amillennialism, where the Christ rules the earth spiritually through his triumphant church.[23] At the Reformation, theologians such as John Calvin accepted amillennialism while rejecting aspects of mediaeval ecclesiology which had been built on Augustine's teaching.

Augustine taught that the eternal fate of the soul is determined at death,[20][24] and that purgatorial fires of the intermediate state purify only those that died in communion with the Church. His teaching provided fuel for later theology.[20]

[edit] Just War

Augustine developed a theology of just war, that is, war that is acceptable under certain conditions. Firstly, war must occur for a good and just purpose rather than for self-gain or as an exercise of power. Secondly, just war must be waged by a properly instituted authority such as the state. Thirdly, love must be a central motive even in the midst of violence.[25]

[edit] Augustine and lust

Augustine struggled with lust throughout his life. He associated sexual desire with the sin of Adam, and believed that it was still sinful, even though the Fall has made it part of human nature.

In the Confessions, Augustine describes his personal struggle in vivid terms: "But I, wretched, most wretched, in the very commencement of my early youth, had begged chastity of Thee, and said, 'Grant me chastity and continence, only not yet.'"[26] At sixteen Augustine moved to Carthage where again he was plagued by this "wretched sin":

There seethed all around me a cauldron of lawless loves. I loved not yet, yet I loved to love, and out of a deep-seated want, I hated myself for wanting not. I sought what I might love, in love with loving, and I hated safety... To love then, and to be beloved, was sweet to me; but more, when I obtained to enjoy the person I loved. I defiled, therefore, the spring of friendship with the filth of concupiscence, and I beclouded its brightness with the hell of lustfulness.

– [27]

For Augustine, the evil was not in the sexual act itself, but rather in the emotions that typically accompany it. To the pious virgins raped during the sack of Rome, he writes, "Truth, another's lust cannot pollute thee." Chastity is "a virtue of the mind, and is not lost by rape, but is lost by the intention of sin, even if unperformed."[22]

In short, Augustine's life experience led him to consider lust to be one of the most grievous sins, and a serious obstacle to the virtuous life.

[edit] The Jews

Against certain Christian movements rejecting the use of Hebrew Scriptures, Augustine countered that God had chosen the Jews as a special people, though he also considered the scattering of Jews by the Roman empire to be a fulfillment of prophecy.[28] [29]

Augustine also quotes part of the same prophecy that says "Slay them not, lest they should at last forget Thy law". Augustine argued that God had allowed the Jews to survive this dispersion as a warning to Christians, thus they were to be permitted to dwell in Christian lands. Augustine further argued that the Jews would be converted at the end of time.[30]

[edit] Prophetic Exegesis

| This article or section may contain original research or unverified claims. Please improve the article by adding references. See the talk page for details. (December 2007) |

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Please see the discussion on the talk page. This section has been tagged since December 2007. |

Augustine spoke on prophetic exegesis in his book “The City of God.”[31]

[edit] Mystical Babylon

Augustine applied the term "Babylon" to Rome calling it "western Babylon," and "mystical Babylon":

"Babylon, like a first Rome, ran its course along with the city of God. . . . Rome herself is like a second Babylon."[32]

"The city of Rome was founded, like another Babylon, and as it were the daughter of the former Babylon, by which God was pleased to conquer the whole world, and subdue it far and wide by bringing it into one fellowship of government and laws.”[33]

[edit] Four Kingdoms followed by Antichrist

Augustine commends the reading of Jerome.

"In prophetic vision he [Daniel] had seen four beasts, signifying four kingdoms, and the fourth conquered by a certain king, who is recognized as Antichrist, and after this the eternal kingdom of the Son of man, that is to say, of Christ. . . . Some have interpreted these four kingdoms as signifying those of the Assyrians, Persians, Macedonians, and Romans. They who desire to understand the fitness of this interpretation may read Jerome's book on Daniel, which is written with a sufficiency of care and erudition."[34]

[edit] Antichrist in the Church?

Augustine inclined toward the idea that the Antichrist or Man of Sin would be an apostate body in the church itself.

"It is uncertain in what temple he shall sit, whether in that ruin of the temple which was built by Solomon, or in the Church; for the apostle would not call the temple of any idol or demon the temple of God. And on this account some think that in this passage Antichrist means not the prince himself alone, but his whole body, that is, the mass of men who adhere to him, along with him their prince: and they also think that we should render the Greek more exactly were we to read, not 'in the temple of God,' but 'for' or 'as the temple of God,' is if he himself were the temple of God, the Church."[35]

[edit] To reign three and a half years

Augustine expected the antichrist to reign three years and a half

"But he who reads this passage, even half asleep, cannot fail to see that the kingdom of Antichrist shall fiercely, though for a short time, assail the Church before the last judgment of God shall introduce the eternal reign of the saints. For it is patent from the context that time, times and half a time, means a year, and two years, and half a year, that is to say, three years and a half. Sometimes in Scripture the same thing is indicated by months. For though the word times seems to be used here in the Latin indefinitely, that is only because the Latins have no dual, as the Greeks have, and as the Hebrews also are said to have. Times, therefore, is used for two times.”[36]

[edit] St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas

For quotations of St. Augustine by St. Thomas Aquinas see Aquinas and the Sacraments and Thought of Thomas Aquinas Part I.

[edit] Books

- On Christian Doctrine, 397-426

- Confessions, 397-398

- The City of God, begun ca. 413, finished 426

- On the Trinity, 400-416

- Enchiridion

- Retractions: At the end of his life (ca. 426-428) Augustine revisited his previous works in chronological order and suggested what he would have said differently in a work titled the Retractions, giving the reader a rare picture of the development of a writer and his final thoughts.

- The Literal Meaning of Genesis

- On Free Choice of the Will

[edit] Letters

|

|

[edit] Notes

- ^ Archimandrite [now Archbishop] Chrysostomos. "Book Review: The Place of Blessed Augustine in the Orthodox Church". Orthodox Tradition II (3&4): 40-43. Retrieved on 2007-06-28.

- ^ "Blessed Augustine of Hippo: His Place in the Orthodox Church: A Corrective Compilation". Orthodox Tradition XIV (4): 33-35. Retrieved on 2007-06-28.

- ^ "Carthage was also near the countries over the sea, and distinguished by illustrious renown,so that it had a bishop of more than ordinary influence, who could afford to disregard a number of conspiring enemies because he saw himself joined by letters of communion to the Roman Church, in which the supremacy of an apostolic chair has always flourished" Letter 43 Chapter 9

- ^ Patricia Hampl. The Confessions by St Augustine (preface). Vintage, 1998. ISBN 0375700218 - Marcus Dods. The City of God by St Augustine (preface). Modern Library edition, 2000. ISBN 0679783199 - Norman Cantor. The Civilization of the Middle Ages, A Completely Revised and Expanded Edition of Medieval History p74. Harper Perennial, 1994. ISBN 0060925531 - Vincent Serralda. Le Berbère...lumière de l'Occident. Nouvelles Editions Latines, 1989. ISBN 2723302393 - René Pottier. Saint Augustin le Berbère. Fernand Lanore, 2006. ISBN 2851572822 - Gabriel Camps. Les Berbères. Editions de France, 1995. ISBN 978-2877722216 - Gilbert Meynier. L'Algérie des origines p73. La Découverte, 2007. ISBN 2707150886 etc

- ^ a b c d e f g h Encyclopedia Americana, v.2, p. 685. Danbury, CT:Grolier Incorporated, 1997. ISBN 0-7172-0129-5.

- ^ Andrew Knowles and Pachomios Penkett, Augustine and his World Ch.2.

- ^ Monica was a Berber name derived from the Libyan deity Mon worshiped in the neighbouring town of Thibilis. However, we don’t have any information that Monica’s husband was a Berber too.

- ^ According to J.Fersuson and Garry Wills, Adeodatus, the name of Augustine's son is a Latinization of the Berber name Iatanbaal (given by God).

- ^ Passage based on F.A. Wright and T.A. Sinclair, A History of Later Latin Literature (London 1931), pp. 56 ff.

- ^ Thomas Cahill, How the Irish Saved Civilization Ch.2.

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (Penguin Group, 2005) p112.

- ^ History of Western Philosophy, 1946, reprinted Unwin Paperbacks 1979, pp 352-3

- ^ Confessiones Liber X: commentary on 10.8.12 (in Latin)

- ^ J.-P. Migne, (translator) St. Augustine's Letter 211 (ed.) Patrologiae Latinae Volume 33, (1845).

- ^ Augustine of Hippo The Confessions

- ^ Augustine of Hippo Sermons 358,1 "Victoria veritatis est caritas"

- ^ Augustine of Hippo Sermons 336, 1 PL 38, 1472

- ^ Augustine of Hippo Sermon on 1 John 7, 8 [1] Cf. Augustine On Galatians 6:1: "And if you shout at him, love him inwardly; you may urge, wheedle, rebuke, rage; love, and do whatever you wish. A father after all, doesn’t hate his son; and if necessary, a father gives his son a whipping; he inflicts pain, to insure well-being. So that’s the meaning of in a spirit of mildness (Gal. 6:1).” Sermon 163B:3:1, The Works of Saint Augustine: A New Translation for the 21st Century, (Sermons 148-153), 1992, part 3, vol. 5, p. 182. ISBN 1565480074

- ^ Augustine's Confessions : critical essaysedited by William E. Mann. Lanham, Md. : Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006. - xii, 240 s

- ^ a b c d e f Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ a b c d e f Justo L. Gonzalez (1970-1975). A History of Christian Thought: Volume 2 (From Augustine to the eve of the Reformation). Abingdon Press.

- ^ a b c d Catholic Encyclopedia (1914)

- ^ Craig L. Blomberg (2006). From Pentecost to Patmos. Apollos, 519.

- ^ Enchiridion 110

- ^ Justo L. Gonzalez (1984). The Story of Christianity. HarperSanFrancisco.

- ^ [2]Confessions, Saint Augustine, Book Eight, Chapter 17.

- ^ [3] Confessions, Saint Augustine, Book Three, Chapter 1.

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch. The Reformation (Penguin Group, 2005) p8.

- ^ City of God, book 18, chapter 46.

- ^ J. Edwards, The Spanish Inquisition (Stroud, 1999), pp33-5.

- ^ Froom, L.E., 1950, "The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers," Vol. 1, Chp. 20, pp. 473-491

- ^ “City of God” Book 18, Chapter 2

- ^ “City of God” Book 18, Chapter 22

- ^ “City of God” Book 20, Chapter 23

- ^ “City of God” Book 20, Chapter 19

- ^ “City of God” Book 20, Chapter 23

[edit] References

- The Story of Thought, DK Publishing, Bryan Magee, London, 1998, ISBN 0-7894-4455-0

- aka The Story of Philosophy, Dorling Kindersley Publishing, 2001, ISBN 0-7894-7994-X

- (subtitled on cover: The Essential Guide to the History of Western Philosophy)

- g Saint Augustine, pages 30, 144; City of God 51, 52, 53 and The Confessions 50, 51, 52

- - additional in the Dictionary of the History of Ideas for Saint Augustine and Neo-Platonism

[edit] In the arts

- Indie/rock band Band of Horses have a song called "St. Augustine". It seems that the song speaks of somebody's desire for fame and recognition, rather than their desire for truth.

- Christian rock band Petra dedicated a song to St. Augustine called "St. Augustine's Pears". It is based on one of Augustine's writings in his book "Confessions" where he tells of how he stole some neighbor's pears without being hungry, and how that petty theft haunted him through his life.[5]

- Jon Foreman, lead singer and song writer of the alternative rock band Switchfoot wrote a song called "Something More (Augustine's Confession)", based after the life and book, "Confessions", of Augustine.

- For his 1993 album "Ten Summoner's Tales", Sting wrote a song entitled "Saint Augustine in Hell", with lyrics 'Make me chaste, but not just yet' alluding to Augustine's famous prayer, 'Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet'.

- Bob Dylan, for his 1967 album John Wesley Harding penned a song entitled "I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine" (also covered by Thea Gilmore in her 2002 album Songs from the Gutter.). The song's opening lines ("I dreamed I saw Saint Augustine / Alive as you or me") are likely based on the opening lines of " I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night", a song crafted in 1936 by Earl Robinson detailing the death of the famous American labor-activist who, himself, was an influential songwriter.

- Roberto Rossellini directed the film "Agostino d'Ippona" (Augustine of Hippo) for Italy's RAI-TV in 1972.

- Alternative rock band Sherwood's album "Sing, But Keep Going" references a famous quote attributed to St. Augustine on the inside cover.

- After being unintentionally baptised by Ned Flanders in episode '3F01' - "Home Sweet Home - Diddily-Dum-Doodily", Homer Simpson says, "Oh, Bartholomew, I feel like St. Augustine of Hippo after his conversion by Ambrose of Milan."

- Christian singer Kevin Max mentions St. Augustine in his song "Angel With No Wings". He sings So come on back when you can make some tea/And read Saint Augustine.

[edit] Bibliography

- Brown, Peter. Augustine of Hippo. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967. ISBN 0-520-00186-9

- Gareth B. Matthews. Augustine. Blackwell, 2005. ISBN 0-631-23348-2

- O'Donnell, James J. Augustine: A New Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 2005. ISBN 0-06-053537-7

- Ruickbie, Leo. Witchcraft Out of the Shadows. London: Robert Hale, 2004. ISBN 0-7090-7567-7, pp. 57-8.

- Tanquerey, Adolphe. The Spiritual Life: A Treatise on Ascetical and Mystical Theology. Reprinted Ed. (original 1930). Rockford, IL: Tan Books, 2000. ISBN 0-89555-659-6, p. 37.

- von Heyking, John. Augustine and Politics as Longing in the World. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8262-1349-9

- Orbis Augustinianus sive conventuum O. Erem. S. A. chorographica et topographica descriptio Augustino Lubin, Paris, 1659, 1671, 1672.

- Regle de St. Augustin pour les religieuses de son ordre; et Constitutions de la Congregation des Religieuses du Verbe-Incarne et du Saint-Sacrament (Lyon: Chez Pierre Guillimin, 1662), pp. 28-29. Cf. later edition published at Lyon (Chez Briday, Libraire,1962), pp. 22-24. English edition, The Rule of Saint Augustine and the Constitutions of the Order of the Incarnate Word and Blessed Sacrament (New York: Schwartz, Kirwin, and Fauss, 1893), pp. 33-35.

- Zumkeller O.S.A.,Adolar (1986). Augustine's ideal of Religious life. Fordham University Press, New York.

- Zumkeller O.S.A.,Adolar (1987). Augustine's Rule. Augustinian Press, Villanova,

Pennsylvania U.S.A..

- René Pottier. Saint Augustin le Berbère. Fernand Lanore , 2006. ISBN 2851572822

- Fitzgerald, Allan D., O.S.A., General Editor (1999). Augustine through the Ages: An Encyclopedia. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.,. ISBN 0-8028-3843-X

- Plumer, Eric Antone, (2003). Augustine's Commentary on Galatians. Oxford [England] ; New York : Oxford University Press,. ISBN 0199244391 ISBN 9780199244393 Preview from Google

[edit] See also

[edit] External links

| The external links in this article may not comply with Wikipedia's content policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links. |

- General:

- At UPenn: Texts, translations, introductions, commentaries...

- EarlyChurch.org.uk Extensive bibliography and on-line articles.

- Life of St. Augustine of Hippo, from the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Augstine of Hippo , at Centropian

- Texts by Augustine:

- Works by Augustine of Hippo at Project Gutenberg

- In Latin, at The Latin Library: books and letters by Augustine

- At "Christian Classics Ethereal Library" Translations of several works by Augustine, incl. introductions

- The Enchiridion by Augustine

- [6] Full Latin and Italian text resource

- At "IntraText Digital Library": Works by Augustine in several languages, with concordance and frequency list

- St. Augustine's Multilingual Opera Omnia

- Texts on Augustine:

- On Music

- On Original Sin ask Dan Santos

- Links to the Augustinian Order

- Audio books

- Augustine and Orthodoxy

- Log in to post comments