69AD The Year of the Four Emperors

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Year_of_the_Four_Emperors

Year of the Four Emperors

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|||||

| This article includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. (April 2009) |

The Year of the Four Emperors was a year in the history of the Roman Empire, AD 69, in which four emperors ruled in a remarkable succession. These four emperors were Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian.

The forced suicide of emperor Nero, in 68, was followed by a brief period of civil war, the first Roman civil war since Mark Antony's death in 30 BC. Between June of 68 and December of 69, Rome witnessed the successive rise and fall of Galba, Otho and Vitellius until the final accession of Vespasian, first ruler of the Flavian Dynasty. This period of civil war has become emblematic of the cyclic political disturbances in the history of the Roman Empire. The military and political anarchy created by this civil war had serious repercussions, such as the outbreak of the Batavian rebellion.

Contents[hide] |

Succession

Nero to Galba

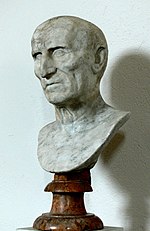

In 65, the Pisonian conspiracy attempted to restore the Republic, but failed. A number of executions followed leaving Nero with few political allies left in the Senate. In late 67 or early 68, Caius Julius Vindex, governor of Gallia Lugdunensis rebelled against Nero's tax policy, with the purpose of substituting Servius Sulpicius Galba, governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, for Nero.

Vindex's revolt in Gaul was unsuccessful. The legions stationed at the border to Germania marched to meet Vindex and confront him as a traitor. Led by Lucius Verginius Rufus, the Rhine army defeated Vindex in battle and Vindex killed himself. Galba was at first declared a public enemy by the Senate.

By June of 68, the Senate took the initiative to rid itself of Nero, declaring him a public enemy and Galba emperor. Nymphidius Sabinus, desiring to become emperor himself, bribed the Praetorian Guard to betray Nero. Nero committed suicide. Galba was recognized as emperor and welcomed into the city at the head of his legions, which were: VI Victrix, I Macriana liberatrix, I Adiutrix, III Augusta and VII Gemina.

Galba to Otho

This turn of events gave the German legions not the reward for loyalty that they had expected, but rather accusations of having obstructed Galba's path to the throne. Their commander, Rufus, was immediately replaced by the new emperor. Aulus Vitellius was appointed governor of the province of Germania Inferior. The loss of political confidence in Germania's loyalty also resulted in the dismissal of the Imperial Batavian Bodyguards and rebellion.

Galba did not remain popular for long. On his march to Rome, he either destroyed or took enormous fines from towns that did not accept him immediately. In Rome, Galba cancelled all the reforms of Nero, including benefits for many important persons. Like his predecessor, Galba had a fear of conspirators and executed many senators and equites without trial. The army was not happy either. After his safe arrival to Rome, Galba refused to pay the rewards he had promised to soldiers who had supported him. Moreover, in the start of the civil year of 69 in January 1, the legions of Germania Inferior refused to swear allegiance and obedience to the new emperor. On the following day, the legions acclaimed Vitellius, their governor, as emperor.

Hearing the news of the loss of the Rhine legions, Galba panicked. He adopted a young senator, Lucius Calpurnius Piso Licinianus, as his successor. By doing this he offended many people, and above all Marcus Salvius Otho, an influential and ambitious man who desired the honour for himself. Otho bribed the Praetorian Guard, already very unhappy with the emperor, to his side. When Galba heard about the coup d'état he went to the streets in an attempt to normalize the situation. It proved a mistake, because he could attract no supporters. Shortly afterwards, the Praetorian Guard killed him in the Forum.

- Otho's legions: XIII Gemina and I Adiutrix

Otho to Vitellius

Otho was recognised as emperor by the Senate that same day. The new emperor was saluted with relief. Although ambitious and greedy, Otho did not have a record for tyranny or cruelty and was expected to be a fair emperor. However, trouble in the form of Vitellius was marching down on Italy from Germany.

Vitellius had behind him the finest elite legions of the empire, composed of veterans of the Germanic Wars, such as I Germanica and XXI Rapax. These would prove to be his best arguments to gain power. Otho was not keen to begin another civil war and sent emissaries to propose a peace and inviting Vitellius to be his son-in-law. It was too late to reason; Vitellius' generals had half of his army heading to Italy. After a series of minor victories, Otho was defeated in the Battle of Bedriacum. Rather than flee and attempt a counter-attack, Otho decided to put an end to the anarchy and committed suicide. He had been emperor for a little more than three months.

- Vitellius' legions: I Germanica, V Alaudae, I Italica, XV Primigenia, I Macriana liberatrix, III Augusta, and XXI Rapax

- Otho legions: I Adiutrix

Vitellius to Vespasian

On the news of Otho's suicide, Vitellius was recognised as emperor by the Senate. Granted this recognition, Vitellius set out for Rome. However, he faced problems from the start of his reign. The city was left very skeptical when Vitellius chose the anniversary of the Battle of the Allia (in 390 BC), a day of bad auspices according to Roman superstition, to accede to the office of Pontifex Maximus.

Events would seemingly prove them right. With the throne tightly secured, Vitellius engaged in a series of feasts, banquets (Suetonius refers to three a day: morning, afternoon and night) and triumphal parades that drove the imperial treasury close to bankruptcy. Debts were quickly accrued and money-lenders started to demand repayment. Vitellius showed his violent nature by ordering the torture and execution of those who dared to make such demands. With financial affairs in a state of calamity, Vitellius took the initiative of killing citizens who named him as their heir, often together with any co-heirs. Moreover, he engaged in a pursuit of every possible rival, inviting them to the palace with promises of power only to have them assassinated.

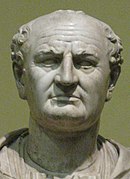

Meanwhile, the legions stationed in the African province of Ægyptus (Egypt) and the Middle East provinces of Iudaea (Judea/Palestine) and Syria had acclaimed Vespasian as emperor. Vespasian had been given a special command in Judaea by Nero in 67 with the task of putting down the Great Jewish Revolt. He gained the support of the governor of Syria, Gaius Licinius Mucianus. A strong force drawn from the Judaean and Syrian legions marched on Rome under the command of Mucianus. Vespasian himself travelled to Alexandria where he had been acclaimed Emperor on July 1, thereby gaining control of the vital grain supplies from Egypt. Vespasian's son Titus remained in Judaea to deal with the Jewish rebellion. Before the eastern legions could reach Rome, the Danubian legions of the provinces of Raetia and Moesia also acclaimed Vespasian as Emperor in August, and led by Marcus Antonius Primus invaded Italy. In October, the forces led by Primus won a crushing victory over Vitellius' army at the Second Battle of Bedriacum.

Surrounded by enemies, Vitellius made a last attempt to win the city to his side, distributing bribes and promises of power where needed. He tried to levy by force several allied tribes, such as the Batavians, only to be refused. The Danube army was now very near Rome. Realising the immediate threat, Vitellius made a last attempt to gain time and sent emissaries, accompanied by Vestal Virgins, to negotiate a truce and start peace talks. The following day, messengers arrived with news that the enemy was at the gates of the city. Vitellius went into hiding and prepared to flee, but decided on a last visit to the palace. There he was caught by Vespasian's men and killed. In seizing the capital, they burned down the temple of Jupiter.

The Senate acknowledged Vespasian as emperor on the following day. It was December 21, 69, the year that had begun with Galba on the throne.

- Vitellius legions: XV Primigenia

- Vespasian legions: III Augusta, I Macriana liberatrix

Aftermath

Vespasian did not meet any direct threat to his imperial power after the death of Vitellius. He became the founder of the stable Flavian dynasty that succeeded the Julio-Claudians and died of natural causes as emperor in 79, with the famous last words, "Vae, puto deus fio" ("Dear me, I must be turning into a god...").

Chronology

68

- April – Galba, governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, and Vindex, governor of Gallia Lugdunensis rebel against Nero

- May – The Rhine legions defeat and kill Vindex in Gaul

- June – Nero is declared a public enemy (hostis) by the senate (June 8) and commits suicide ([June 9); on that same day, Galba is recognized emperor.

- November – Vitellius nominated governor of Germania Inferior

69

- January 1 – The Rhine legions refuse to swear loyalty to Galba

- January 2 – Vitellius acclaimed emperor by the Rhine

- January 15 – Galba killed by the Praetorian Guard; in the same day, the senate recognizes Otho as emperor

- April 14 – Vitellius defeats Otho

- April 16 – Otho commits suicide; Vitellius recognized emperor

- July 1 – Vespasian, commander of the Roman army in Judaea, proclaimed emperor by the legions of Egypt under Tiberius Julius Alexander

- August – The Danubian legions announce support to Vespasian (in Syria) and invade Italy in September on his behalf

- October – The Danube army defeats Vitellius and Vespasian occupies Egypt

- December 20 – Vitellius killed by soldiers in the Imperial Palace

- December 21 – Vespasian recognized emperor

See also

- Tacitus, Histories

- Year of the Five Emperors (193)

- Year of the Six Emperors (238)

- West Indian cricket team in England in 1988, a tour often referred to as the Summer of the four captains

References

- Roman Warfare, Adrian Goldsworthy

- The Twelve Caesars, Suetonius, available from Project Gutenberg: The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Complete

- The year of the four emperors, Peter Greenhalgh (1975)

|

||

- Log in to post comments