1070-REFORMATION History (external support)

The events of World History are listed in this section to illustrate the "spirit of the age" that characterised this dark period between the "Thousand Years" (Millennium) and modern times. This dark period from 1070AD to the Reformation is characterized as follows:

- The New Jerusalem, (ie, the global community of the true Christians), was subjected to same test of Isaiah's day that took away all of Israel & Judah leaving the mother-city Jerusalem alone and surrounded by the horde of enemies on every side. Under siege and threat of extinction, both old and new Jerusalem, (the camp of the saints, the beloved city), were rescued suddenly with divine deliverance that consumed all enemies: old Jerusalem by an angel from heaven, new Jerusalem by fire from heaven.

- God's People under siege on every side, Turks & Wars & Black Death Plagues without and heretics running rampant within, True Faithful Christians face the greatest challenge to their survival since the Roman Empire was overcome for Christ.

- From early Reformers like John Wycliffe to later Reformers like Martin Luther, the period following 1070AD is considered a Dark Age, a challenging season in Christian history. And secular historians have similar words for the period of World history. [It should be mentioned here that I regard the Reformation fires to have begun with the likes of John Wycliffe and ending with the likes of Martin Luther & Jean Calvin. Thus, the Reformation beginning with Wycliffe gave rise to the Renaissance, "the rebirth" that followed. Progress is preceeded by preaching]. Relative to the 1000 year Millennium just finished and Eternity just ahead, this period of Satan's Release is a "short while."

- World History is cited to demonstrate the "zeitgheist" or "spirit of the age" of this dark period before the Reformation fire came like "fire from Heaven" to rescue the faithful from enemies on every side.

"Having given my Conjecture, that the Jewish Church, with their rulers, were the Antichrist mentioned by St. Paul; I proceed to shew, how their Apostasy, when they were thus deserted by God, resembled, and ran Parallel to the Apostasy of the Roman Church." (Additional comments on II Thess. 2). ~ Daniel Whitby (1710)

- Log in to post comments

1070AD-REFORMATION Christianity's greatest trial since the 30-70AD Tribulation

Continued from: The MILLENNIUM = the Middle Age 70-1070AD = The Day of the Lord

I found that shortly after 1070AD, the seeds of discord planted in the 1054AD Schism between Western Catholic & Eastern Orthodox, germinated to produce a harvest of hell, worldwide, including the world-changing devastation of the Black Death Plague. It seemed reasonable to deduce that this period from apx 1070AD to the Reformation/Rennaissance equated to Satan's being loosed and that the "Fire from Heaven" (ie spritual fire) that rescues the Saintly Camp, the Beloved City (Christendom), is equated with The Reformation, the great return to the actual Text of Holy Writ. The blurring inklings of an accomplished Return of Christ began to more fully focus within me as the major puzzle pieces began to fit together. Studiies of Words of Jesus & the Apostles harmonized with the reports of Christians through history to deduce that Jesus must have Returned around the destruction of ancient Jerusalem in 70AD, precisely because the Text demands it at the beginning of the Millennium, the 1000 year reign of the saints; the saints that had been martyred during the Tribulation endured by the Apostle John & the rest; the Tribulation that culminated in same said destruction of Jerusalem in 70AD. This had to mark the Return of Christ/First Resurrection, the beginning of the 1000 year Millennium/Middle Age conquest-rule by Christendom.

1070AD to the Reformation = The Brief Loosing of Satan ending with the Fire from Heaven

- Log in to post comments

1049-1294AD Gregory VII to Boniface VIII: Papal Theocracy in Conflict with the Secular Power

THE PAPAL THEOCRACY IN CONFLICT WITH THE SECULAR POWER

FROM GREGORY VII. TO BONIFACE VIII.

A.D. 1049-1294

Introductory Survey.

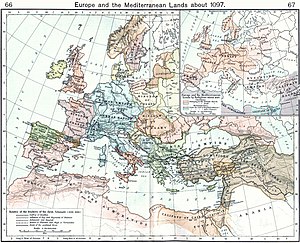

The fifth period of general Church history, or the second period of mediaeval Church history, begins with the rise of Hildebrand, 1049, and ends with the elevation of Boniface VIII. to the papal dignity, 1294.

In this period the Church and the papacy ascend from the lowest state of weakness and corruption to the highest power and influence over the nations of Europe. It is the classical age of Latin Christianity: the age of the papal theocracy, aiming to control the German Empire and the kingdoms of France, Spain, and England. It witnessed the rise of the great Mendicant orders and the religious revival which followed. It beheld the full flower of chivalry and the progress of the crusades, with the heroic conquest and loss of the Holy Land. It saw the foundations laid of the great universities of Bologna, Paris, Oxford. It was the age of scholastic philosophy and theology, and their gigantic efforts to solve all conceivable problems and by dialectical skill to prove every article of faith. During its progress Norman and Gothic architecture began to rear the cathedrals. All the arts were made the handmaids of religion; and legendary poetry and romance flourished. Then the Inquisition was established, involving the theory of the persecution of Jews and heretics as a divine right, and carrying it into execution in awful scenes of torture and blood. It was an age of bright light and deep shadows, of strong faith and stronger superstition, of sublime heroism and wild passions, of ascetic self-denial and sensual indulgence, of Christian devotion and barbarous cruelty. Dante, in his Divina Commedia, which "heaven and earth" combined to produce, gives a poetic mirror of Christianity and civilization in the thirteenth and the opening years of the fourteenth century, when the Roman Church was at the summit of its power, and yet, by the abuse - of that power and its worldliness, was calling forth loud protests, and demands for a thorough reformation from all parts of Western Christendom.

A striking feature of the Middle Ages is the contrast and co-operation of the forces of extreme self-abnegation as represented in monasticism and extreme ambition for worldly dominion as represented in the papacy. The former gave moral support to the latter, and the latter utilized the former. The monks were the standing army of the pope, and fought his battles against the secular rulers of Western Europe.

The papal theocracy in conflict with the secular powers and at the height of its power is the leading topic. The weak and degenerate popes who ruled from 900-1046 are now succeeded by a line of vigorous minds, men of moral as well as intellectual strength. The world has had few rulers equal to Gregory VII. 1073-1085, Alexander III. 1159-1181, and Innocent III. 1198-1216, not to speak of other pontiffs scarcely second to these masters in the art of government and aspiring aims. The papacy was a necessity and a blessing in a barbarous age, as a check upon brute force, and as a school of moral discipline. The popes stood on a much higher plane than the princes of their time. The spirit has a right to rule over the body; the intellectual and moral interests are superior to the material and political. But the papal theocracy carried in it the temptation to secularization. By the abuse of opportunity it became a hindrance to pure religion and morals. Christ gave to Peter the keys of the kingdom of heaven, but he also said, "My kingdom is not of this world" (John 18:36). The pope coveted both kingdoms, and he got what he coveted. But he was not able to hold the power he claimed over the State, and aspiring after temporal authority lost spiritual power. Boniface VIII. marks the beginning of the decline and fall of the papal rule; and the seeds of this decline and fall were sown in the period when the hierarchy was in the pride of its worldly might and glory.

In this period also, and chiefly as the result of the crusades, the schism between the churches of the East and the West was completed. All attempts made at reconciliation by pope and council only ended in wider alienation.

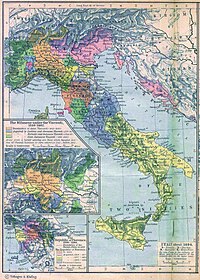

The ruling nations during the Middle Ages were the Latin, who descended from the old Roman stock, but showed the mixture of barbaric blood and vigor, and the Teutonic. The Italians and French had the most learning and culture. Politically, the German nation, owing to its possession of the imperial crown and its connection with the papacy, was the most powerful, especially under the Hohenstaufen dynasty. England, favored by her insular isolation, developed the power of self-government and independent nationality, and begins to come into prominence in the papal administration. Western Europe is the scene of intellectual, ecclesiastical, and political activities of vast import, but its arms and devotion find their most conspicuous arena in Palestine and the East.

Finally this period of two centuries and a half is a period of imposing personalities. The names of the greatest of the popes have been mentioned, Gregory VII., Alexander III., and Innocent III. Its more notable sovereigns were William the Conqueror, Frederick Barbarossa, Frederick II., and St. Louis of France. Dante the poet illumines its last years. St. Bernard, Francis d'Assisi, and Dominic, the Spaniard, rise above a long array of famous monks. In the front rank of its Schoolmen were Anselm, Abelard, Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventura, and Duns Scotus. Thomas à Becket and Grosseteste are prominent representatives of the body of episcopal statesmen. This combination of great figures and of great movements gives to this period a variety of interest such as belongs to few periods of Church history or the history of mankind.

(from Schaff's History of the Church, PC Study Bible formatted electronic database Copyright © 1999, 2003, 2005, 2006 by Biblesoft, Inc. All rights reserved.)

- Log in to post comments

1037-1194AD The Great Seljuk Empire: brought to the Muslims "fighting spirit and fanatical aggression"

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Seljuq_Empire

Great Seljuq Empire

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

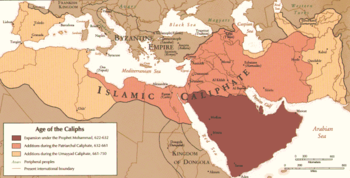

The Great Seljuq Empire was a medievalSunniMuslim empire established by the Qynyq branch of Oghuz Turks[1] that once controlled a vast area stretching from the Hindu Kush to eastern Anatolia and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf. From their homelands near the Aral sea, the Seljuqs advanced first into Khorasan and then into mainland Persia before eventually conquering eastern Anatolia. Their advance marked the beginning of Turkic power in the Middle East.

The Seljuq empire was founded by Tugrul Beg in 1037 after the efforts by the founder of the Seljuq dynasty, Seljuq Beg, back in the first quarter of the 11th century. Seljuq Beg's father was in a higher position in the Oghuz Yabgu State, and gave his name both to the state and the dynasty. The Seljuqs united the fractured political scene of the Eastern Islamic world and played a key role in the first and second crusades. Highly Persianized[2][3] in culture[4] and language[5][6][7][8], the Seljuqs also played an important role in the development of the Turko-Persian tradition which "features Persian culture patronized by Turkic rulers"[9].

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Founder of the Dynasty

The apical ancestor of the Seljuqs was their Beg, Seljuq, who was reputed to have served in the Khazar army, under whom, circa 950 CE they migrated to Khwarezm, near the city of Jend also called Khujand, where they converted to Islam.[10]

[edit] Great Seljuk

The Seljuqs were allied with the Persian Samanid Shahs against the Qarakhanids. The Samanids however fell to the Qarakhanids and the emergence of the Ghaznavids and were involved in the power struggle in the region before establishing their own independent base.

[edit] Tugrul and Chagri Beg

Togrul Beg was the grandson of Seljuk and Çagrı (Chagri) was his brother, under whom the Seljuks wrested an empire from the Ghaznavids. Initially the Seljuks were repulsed by Mahmud and retired to Khwarezm but Togrül and Çagrı led them to capture Merv and Nishapur (1028-1029). Later they repeatedly raided and traded territory with his successors across Khorasan and Balkh and even sacked Ghazni in 1037. In 1039 at the Battle of Dandanaqan, they decisively defeated Mas'ud I of the Ghaznavids resulting in him abandoning most of his western territories to the Seljuks. In 1055, Togrül captured Baghdad from the Shi'a Buyids under a commission from the Abbassids.

[edit] Alp Arslan

Alp Arslan was the son of Chagri Beg and expanded significantly upon Togrül's holdings by adding Armenia and Georgia in 1064 and invading the Byzantine Empire in 1068, from which he annexed almost all of Anatolia; Arslan's decisive victory at the Battle of Manzikert (in 1071) effectively neutralized the Byzantine [1st Christian Empire] threat.[11] He authorized his Turcoman generals to carve their own principalities out of formerly Byzantine Anatolia, as atabegs loyal to him. Within two years the Turcomans had established control as far as the Aegean Sea under numerous "beghliks" (modern Turkish beyliks): the Saltuqis in Northeastern Anatolia, Mengujeqs in Eastern Anatolia, Artuqids in Southeastern Anatolia, Danishmendis in Central Anatolia, Rum Seljuks (Beghlik of Suleyman, which later moved to Central Anatolia) in Western Anatolia and the Beghlik of Çaka Beg in İzmir (Smyrna).

[edit] Malik Shah I

Under Alp Arslan's successor Malik Shah and his two Persian viziers[12]Nizām al-Mulk and Tāj al-Mulk, the Seljuk state expanded in various directions, to former Iranian border before Arab invasion, so that it bordered China in the East and the Byzantines in the West. He moved the capital from Rayy to Isfahan. The Iqta military system and the Nizāmīyyah University at Baghdad were established by Nizām al-Mulk, and the reign of Malikshāh was reckoned the golden age of "Great Seljuk". The Abbasid Caliph titled him "The Sultan of the East and West" in 1087. The Assassins of Hassan-e Sabāh however started to become a force during his era and assassinated many leading figures in his administration.

[edit] Governance

The Seljuk power was at its zenith under Malikshāh I, and both the Qarakhanids and Ghaznavids had to acknowledge the overlordship of the Seljuks.[13]. The Seljuk dominion was established over the ancient Sassanid domains, in Iran and Iraq, and included Anatolia as well as parts of Central Asia and modern Afghanistan.[13] The Seljuk rule was modelled after the tribal organization brought in by the nomadic conquerors and resembled a 'family federation' or 'appanage state'.[13] Under this organization the leading member of the paramount family assigned family members portions of his domains as autonomous appanages.[13]

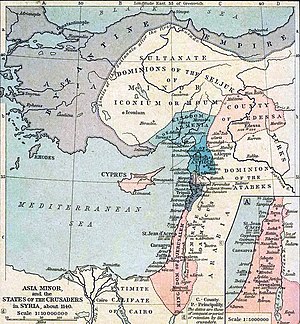

[edit] The First Crusade

The fractured states of the Seljuks were on the whole more concerned with consolidating their own territories and gaining control of their neighbours, than with cooperating against the crusaders when the First Crusade arrived in 1095 and successfully captured the Holy land to set up the Crusader States. The Seljuks had already lost Palestine to the Fatimids before their capture by the crusaders.

[edit] The Second Crusade

- See also: Second Crusade, Zengi, Nur ad-Din

Ahmed Sanjar had to contend with the revolts of Qarakhanids in Transoxiana, Ghorids in Afghanistan and Qarluks in modern Kyrghyzstan, even as the nomadic Kara-Khitais invaded the East destroying the Seljuk vassal state of the Eastern Qarakhanids. At the Battle of Qatwan Sanjar 1141 and lost all his eastern provinces up to the Syr Darya.

During this time conflict with the Crusader States was also intermittent and after the First Crusade, increasingly independent atabegs would frequently ally with the crusader states against other atabegs as they vied with each other for territory. At Mosul Zengi succeeded Kerbogha as atabeg and successfully began the process of consolidating the atabegs of Syria. In 1144 Zengi captured Edessa, as the County of Edessa had allied itself with the Ortoqids against him. This event triggered the launch of the second crusade. Nur ad-Din, one of Zengi's sons who succeeded him as atabeg of Aleppo created an alliance in the region to oppose the second crusade which landed in 1147.

[edit] Division of empire

- See also: Sultanate of Rum, Atabegs

When Malikshāh I died in 1092, the empire split as his brother and four sons quarrelled over the apportioning of the empire among themselves. In Anatolia, Malikshāh I was succeeded by Kilij Arslan I who founded the Sultanate of Rum and in Syria by his brother Tutush I. In Persia he was succeeded by his son Mahmud I whose reign was contested by his other three brothers Barkiyaruq in Iraq, Muhammad I in Baghdad and Ahmad Sanjar in Khorasan.

When Tutush I died his sons Radwan and Duqaq inherited Aleppo and Damascus respectively and contested with each other as well further dividing Syria amongst emirs antagonistic towards each other.

In 1118, the third son Ahmad Sanjar took over the empire. His nephew, the son of Muhammad I did not recognize his claim to the throne and Mahmud II proclaimed himself Sultan and established a capital in Baghdad, until 1131 when he was finally officially deposed by Ahmad Sanjar.

Elsewhere in nominal Seljuk territory were the Artuqids in northeastern Syria and northern Mesopotamia. They controlled Jerusalem until 1098. In eastern Anatolia and northern Syria a state was founded by the Dānišmand dynasty, and contested land with the Sultanate of Rum and Kerbogha exercised greeted independence as the atabeg of Mosul.

[edit] Legacy

The Seljuks were educated in the service of Muslim courts as slaves or mercenaries. The dynasty brought revival, energy, and reunion to the Islamic civilization hitherto dominated by Arabs and Persians. According to the Seljuks, they brought to the Muslims "fighting spirit and fanatical aggression". [14]

The Seljuks were also patrons of art and literature. Under the Seljuks universities were founded.[15] Their reign is characterized by astronomers such as Omar Khayyám, and the philosipher al-Ghazali.

Toghrol Tower, a 12th century monument south of Tehran commemorating Togrul. | The Kharāghān twin towers, built in 1053 CE in Iran, is the burial of Seljuq princes. | Shatranj chess set, glazed fritware, 12th century, from Iran. New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

[edit] List of Emperors of the Great Seljuq Empire

- Selçuk Beg (named after)

- Tuğrul Beg (1040 - 1063) (the founder)

- Alp Arslan (1063 - 1072)

- Melik Şah I (1072 - 1092)

- Mahmud (1092 - 1093)

- Rükneddin (1093 - 1104)

- Melik Şah II (1104 - 1105)

- Mehmed (1105 - 1118)

- Mu'izzeddin (1118 - 1157)

- Karacalı Aslan

[edit] Conquest by Khwarezm and the Ayyubids

| This article or section needs copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone or spelling. You can assist by editing it now. A how-to guide is available.(October 2007) |

- See also:Saladin, Ayyubid, Khwarezmid Empire

In 1153 the Oghuz Turks rebelled and captured Sanjar. He managed to escape three years later but died a year after that. Despite several attempts to reunite the Seljuks by his successors, the Crusades prevented them from regaining their former empire. The Atabegs such as Zengids and Artuqids were only nominally under the Seljuk Sultan, and generally controlled Syria independently. When Ahmed Sanjar died in 1156 it fractured the empire even further rendering the atabegs effectively independent.

- Khorasani Seljuks in Khorasan and Transoxiana. Capital: Merv

- Kermani Seljuks

- Sultanate of Rum. Capital: Iznik (Nicaea), later Konya (Iconium)

- Atabeghlik of Salgur in Iran

- Atabeghlik of Ildeniz in Iraq and Azerbaijan. Capital Hamadan

- Atabeghlik of Bori in Syria. Capital: Damascus

- Atabeghlik of Zangi in Al Jazira (Northern Mesopotamia). Capital: Mosul

- Turcoman Beghliks: Danishmendis, Artuqids, Saltuqis and Mengujegs in Asia Minor

- Khwarezmshahs in Transoxiana, Khwarezm. Capital: Urganch

After the Second Crusade Nur ad-Din's general Shirkuh, who had established himself in Egypt on Fatimid land, was succeeded by Saladin who rebelled against Nur ad-Din. Upon Nur ad-Dins death, Saladin married his widow and captured most of Syria creating the Ayyubid dynasty.

On other fronts the Kingdom of Georgia began to become a regional power and extended its borders at the expense of Great Seljuk as did the revival of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia under Leo II of Armenia in Anatolia. The Abbassid caliph An-Nasir also began to reassert the authority of the caliph and allied himself with the Khwarezmshah Ala ad-Din Tekish.

For a brief period Togrul III was the Sultan of all Seljuk except for Anatolia. In 1194 Togrul was defeated by Ala ad-Din Tekish, the Shah of Khwarezmid Empire, and the Seljuk finally collapsed. Of the former Seljuk Empire, only the Sultanate of Rüm in Anatolia remained. As the dynasty declined in the middle of the 13th century, the Mongols invaded Anatolia in the 1260s and divided it into small emirates called the Anatolian beyliks, one of which, the Ottoman, would rise to power and conquer the rest.

[edit] Notes

- ^

- Jackson, P. (2002). Review: The History of the Seljuq Turks: The History of the Seljuq Turks.Journal of Islamic Studies 2002 13(1):75-76; doi:10.1093/jis/13.1.75.Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies.

- Bosworth, C. E. (2001). Notes on Some Turkish Names in Abu 'l-Fadl Bayhaqi's Tarikh-i Mas'udi. Oriens, Vol. 36, 2001 (2001), pp. 299-313.

- Dani, A. H., Masson, V. M. (Eds), Asimova, M. S. (Eds), Litvinsky, B. A. (Eds), Boaworth, C. E. (Eds). (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (Pvt. Ltd).

- Hancock, I. (2006). ON ROMANI ORIGINS AND IDENTITY. The Romani Archives and Documentation Center. The University of Texas at Austin.

- Asimov, M. S., Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). (1998). History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV: The Age of Achievement: AD 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century, Part One: The Historical, Social and Economic Setting. Multiple History Series. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Dani, A. H., Masson, V. M. (Eds), Asimova, M. S. (Eds), Litvinsky, B. A. (Eds), Boaworth, C. E. (Eds). (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (Pvt. Ltd).

- ^ M.A. Amir-Moezzi, "Shahrbanu", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK): "... here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkish heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- ^

- Josef W. Meri, "Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia", Routledge, 2005, p. 399

- Michael Mandelbaum, "Central Asia and the World", Council on Foreign Relations (May 1994), p. 79

- Jonathan Dewald, "Europe 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World", Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, p. 24: "Turcoman armies coming from the East had driven the Byzantines out of much of Asia Minor and established the Persianized sultanate of the Seljuks."

- ^

- C.E. Bosworth, "Turkish Expansion towards the west" in UNESCO HISTORY OF HUMANITY, Volume IV, titled "From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century", UNESCO Publishing / Routledge, p. 391: "While the Arabic language retained its primacy in such spheres as law, theology and science, the culture of the Seljuk court and secular literature within the sultanate became largely Persianized; this is seen in the early adoption of Persian epic names by the Seljuq Rulers (Qubad, Kay Khusraw and so on) and in the use of Persian as a literary language (Turkish must have been essentially a vehicle for every days speech at this time). The process of Persianization accelerated in the thirteenth century with the presence in Konya of two of the most distinguished refugees fleeing before the Mongols, Baha al-din Walad and his son Mawlana Jalal al-din Rumi, whose Mathnawi, composed in Konya, constitutes one of the crowing glories of classical Persian literature."

- Mehmed Fuad Koprulu's, "Early Mystics in Turkish Literature", Translated by Gary Leiser and Robert Dankoff , Routledge, 2006, pg 149: "If we wish to sketch, in broad outline, the civilization created by the Seljuks of Anatolia, we must recognize that the local, i.e. non-Muslim, element was fairly insignificant compared to the Turkish and Arab-Persian elements, and that the Persian element was paramount. The Seljuk rulers, to be sure, who were in contact with not only Muslim Persian civilization, but also with the Arab civilizations in al-jazlra and Syria - indeed, with all Muslim peoples as far as India — also had connections with {various} Byzantine courts. Some of these rulers, like the great 'Ala' al-Dln Kai-Qubad I himself, who married Byzantine princesses and thus strengthened relations with their neighbors to the west, lived for many years in Byzantium and became very familiar with the customs and ceremonial at the Byzantine court. Still, this close contact with the ancient Greco-Roman and Christian traditions only resulted in their adoption of a policy of tolerance toward art, aesthetic life, painting, music, independent thought - in short, toward those things that were frowned upon by the narrow and piously ascetic views {of their subjects}. The contact of the common people with the Greeks and Armenians had basically the same result. {Before coming to Anatolia,} the Turks had been in contact with many nations and had long shown their ability to synthesize the artistic elements that thev had adopted from these nations. When they settled in Anatolia, they encountered peoples with whom they had not yet been in contact and immediately established relations with them as well. Ala al-Din Kai-Qubad I established ties with the Genoese and, especially, the Venetians at the ports of Sinop and Antalya, which belonged to him, and granted them commercial and legal concessions. Meanwhile, the Mongol invasion, which caused a great number of scholars and artisans to flee from Turkistan, Iran, and Khwarazm and settle within the Empire of the Seljuks of Anatolia, resulted in a reinforcing of Persian influence on the Anatolian Turks. Indeed, despite all claims to the contrary, there is no question that Persian influence was paramount among the Seljuks of Anatolia. This is clearly revealed by the fact that the sultans who ascended the throne after Ghiyath al-Din Kai-Khusraw I assumed titles taken from ancient Persian mythology, like Kai-Khusraw, Kai-Ka us, and Kai-Qubad; and that. Ala' al-Din Kai-Qubad I had some passages from the Shahname inscribed on the walls of Konya and Sivas. When we take into consideration domestic life in the Konya courts and the sincerity of the favor and attachment of the rulers to Persian poets and Persian literature, then this fact {i.e. the importance of Persian influence} is undeniable. With- regard to the private lives of the rulers, their amusements, and palace ceremonial, the most definite influence was also that of Iran, mixed with the early Turkish traditions, and not that of Byzantium."

- Stephen P. Blake, "Shahjahanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India, 1639-1739". Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 123: "For the Seljuks and Il-Khanids in Iran it was the rulers rather than the conquered who were "Pesianized and Islamicized"

- ^ O.Özgündenli, "Persian Manuscripts in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Libraries", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK)

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, "Seljuq", Online Edition, (LINK): "... Because the Turkish Seljuqs had no Islamic tradition or strong literary heritage of their own, they adopted the cultural language of their Persian instructors in Islam. Literary Persian thus spread to the whole of Iran, and the Arabic language disappeared in that country except in works of religious scholarship ..."

- ^ M. Ravandi, "The Seljuq court at Konya and the Persianisation of Anatolian Cities", in Mesogeios (Mediterranean Studies), vol. 25-6 (2005), pp. 157-69

- ^

- M.A. Amir-Moezzi, "Shahrbanu", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK): "... here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkish heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- F. Daftary, Sectarian and National Movements in Iran, Khorasan, and Trasoxania during Umayyad and Early Abbasid Times, in History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol 4, pt. 1; edited by M.S. Asimov and C.E. Bosworth; UNESCO Publishing, Institute of Ismaili Studies: "... Not only did the inhabitants of Khurasan not succumb to the language of the nomadic invaders, but they imposed their own tongue on them. The region could even assimilate the Turkic Ghaznavids and Seljuks (eleventh and twelfth centuries), the Timurids (fourteenth–fifteenth centuries), and the Qajars (nineteenth–twentieth centuries) ..."

- ^ Daniel Pipes: "The Event of Our Era: Former Soviet Muslim Republics Change the Middle East" in Michael Mandelbaum,"Central Asia and the World: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkemenistan and the World", Council on Foreign Relations, pg 79. Exact statement: "In Short, the Turko-Persian tradition featured Persian culture patronized by Turcophone rulers."

- ^ Wink, Andre, Al Hind the Making of the Indo Islamic World, Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 90-04-09249-8 pg.9

- ^ Dhu'l Qa'da 463/ August 1071 The Battle of Malazkirt (Manzikert), <http://www.princeton.edu/~humcomp/kemal/malazf.htm>. Retrieved on 8 September 2007

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, "Nizam al-Mulk", Online Edition, (LINK)

- ^ a b c d Wink, Andre, Al Hind the Making of the Indo Islamic World, Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 90-04-09249-8 pg 9-10

- ^ Previte-Orton (1971), vol.1, pg. 278-9

- ^ two examples are: the Nizamiyah universities of Baghdad and Nishapur

[edit] References

| History of Greater Iran |

|---|

| Empires of Persia · Kings of Persia |

| Pre-modern |

Modern |

- Previte-Orton, C. W (1971). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[edit] See also

- Atabeg

- Assassins

- Artuqid

- Danishmend

- Ghaznavid Empire

- Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm

- Ottoman Empire

- Seljuk

- Seldschuken-Fürsten, list of Seljuk rulers in the German Wikipedia

- Turkic migrations

[edit] External links

| [hide] History of Turkey | |

|---|---|

| Seljuk Turks(1000–1300) · Sultanate of Rum(1060–1327) · Anatolian beyliks(13th century) | |

(1299–1923) | Rise (1299–1453) · Fall of Constantinople Growth (1453–1683) |

| European Wars · Russian Wars · Near East Wars · Capitulations | |

(1919 – Present) | War of Independence (1919–1923) Single-Party Period (1923–1945) Multi-Party Period (1945 – Present) |

| Timeline of Independence · Timeline of Turkey · Economic History · Constitutional History · Military History | |

Categories: Former empires | 1037 establishments | 1194 disestablishments | Wikipedia articles needing copy edit from October 2007 | All articles needing copy edit | Seljuk Turks | History of the Turkic people | History of the Turkish people | Oghuz Turks | Nation timelines | History of Turkey | Turkey-related lists | Sunni Islam | Crusades | Anatolia | History of Iran | History of Pakistan | Muslim dynasties | National histories

- Log in to post comments

1070AD Seljuk Turks take Jerusalem & threaten all Christendom

From: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Catholic_Encyclopedia_(1913)/Crusades

I. ORIGIN OF THE CRUSADES

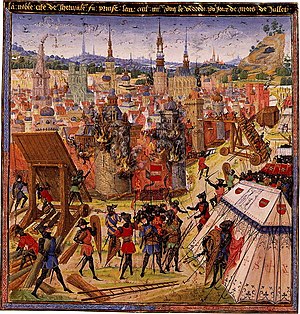

...Instead of diminishing, the enthusiasm of Western Christians for the pilgrimage to Jerusalem seemed rather to increase during the eleventh century. Not only princes, bishops, and knights, but even men and women of the humbler classes undertook the holy journey (Radulphus Glaber, IV, vi). Whole armies of pilgrims traversed Europe, and in the valley of the Danube hospices were established where they could replenish their provisions. In 1026 Richard, Abbot of Saint-Vannes, led 700 pilgrims into Palestine at the expense of Richard II, Duke of Normandy. In 1065 over 12,000 Germans who had crossed Europe under the command of Günther, Bishop of Bamberg, while on their way through Palestine had to seek shelter in a ruined fortress, where they defended themselves against a troop of Bedouins (Lambert of Hersfeld, in "Mon. Germ. Hist.: Script.", V, 168). Thus it is evident that at the close of the eleventh century the route to Palestine was familiar enough to Western Christians who looked upon the Holy Sepulchre as the most venerable of relics and were ready to brave any peril in order to visit it. The memory of Charlemagne's protectorate still lived, and a trace of it is to be found in the medieval legend of this emperor's journey to Palestine (Gaston Paris in "Romania", 1880, p. 23).

The rise of the Seljukian Turks, however, compromised the safety of pilgrims and even threatened the independence of the Byzantine Empire and of all Christendom. In 1070 Jerusalem was taken, and in 1091 Diogenes, the Greek emperor, was defeated and made captive at Mantzikert. Asia Minor and all of Syria became the prey of the Turks. Antioch succumbed in 1084, and by 1092 not one of the great metropolitan sees of Asia remained in the possession of the Christians. Although separated from the communion of Rome since the schism of Michael Cærularius (1054), the emperors of Constantinople implored the assistance of the popes; in 1073 letters were exchanged on the subject between Michael VII and Gregory VII. The pope seriously contemplated leading a force of 50,000 men to the East in order to re-establish Christian unity, repulse the Turks, and rescue the Holy Sepulchre. But the idea of the crusade constituted only a part of this magnificent plan. (The letters of Gregory VII are in P.L., CXLVIII, 300, 325, 329, 386; cf. Riant's critical discussion in Archives de l'Orient Latin, I, 56.) The conflict over the Investitures in 1076 compelled the pope to abandon his projects; the Emperors Nicephorus Botaniates and Alexius Comnenus were unfavourable to a religious union with Rome; finally war broke out between the Byzantine Empire and the Normans of the Two Sicilies....

- Log in to post comments

1071AD Battle of Manzikert - Seljuk Turks begin destruction of Byzantine (1st Christian) Empire

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Manzikert

Battle of Manzikert

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Battle of Manzikert | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Byzantine-Seljuk wars | |||||||

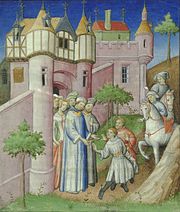

In this 15th-century French miniature depicting the Battle of Manzikert, the combatants are clad in contemporary Western European armour. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Romanus IV #, Nikephoros Bryennios, Theodore Alyates, Andronikos Doukas | Alp Arslan | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~ 20,000 [2] (40,000 initial) | ~ 20,000 [3] - 70,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| ~ 8,000 [4] | Unknown | ||||||

The Battle of Manzikert, or Malazgirt was fought between the Byzantine Empire and Seljuq forces led by Alp Arslan on August 26, 1071 near Manzikert, Armenia (modern Malazgirt, Turkey) in the Basprakania [4] theme (province) of the Empire. It resulted in the defeat of the Byzantine Empire and the capture of Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes. The Battle of Manzikert played an important role in breaking the Byzantine resistance and preparing the way for the Turkish settlement in Anatolia.[5]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Background

Although the Byzantine Empire had remained a strong and powerful entity in the Middle Ages,[6] the Kingdom began to decline under the reign of the militarily incompetent Constantine IX and again under Constantine X - a brief two year rule of reform under Isaac I Komnenus only delaying the decay of the Byzantine military.[7] It was under Constantine IX's reign that the Byzantines first came into contact with the Seljuk Turks, the latter attempting to anex Ani in Armenia. Rather than deal with the problem by force of arms, Constantine IX signed a truce. The truce did not last; in 1063 the Great Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan came to power and thus the invasion of Armenia, halted in 1045, began again.

During the 1060s, the Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan allowed his Turkish allies (Turks and Turkmens), as well as the Kurds, to migrate towards Armenia and Asia Minor. In 1064, they conquered the Armenian capital at Ani.[6] Constantine X (successor to Isaac Komnenus) did much discredit to his predecessor - in 1067 Armenia was taken by the Turks, followed by Caesarea.[8] In 1068, Romanos IV took power and after a few speedy military reforms led an expedition against the Seljuks, allowing him to capture the city of Hierapolis Bambyce in Syria. A Turkic attack against Iconium was thwarted when a Byzantine counter from Syria ended in victory.[9] In 1070, Romanus led a second expedition towards Malazgirt (then known as Manzikert) in the eastern end of Anatolia (in today's Muş Province), where a Byzantine fortress had been captured by the Seljuks, and offered a treaty with Alp Arslan; Romanos would give back Hierapolis if Arslan gave up the siege of Edessa (Urfa). Romanos threatened war if Alp Arslan did not comply, and prepared his troops anyway, expecting the sultan to decline his offer, which he did.

[edit] Preparations

Accompanying Romanos was Andronikos Doukas, the co-regent and a direct rival. The army consisted of about 5,000 Byzantine troops from the western provinces and probably about the same number from the eastern provinces; 500 Frankish and Norman mercenaries under Roussel de Bailleul; some Turkish, Bulgarian, and Pecheneg mercenaries; infantry under the duke of Antioch; a contingent of Armenian troops; and some (but not all) of the Varangian Guard, to total around 60-70,000 troops.[10] The quality of the Byzantine Thematic (provincial) troops had declined in the years prior to the succession of Romanus as the central government diverted resources to the recruitment of mercenaries who were considered less likely to become involved in coups or factional fighting within the Empire. Even when mercenaries were used, they were disbanded after to save money.

The march across Asia Minor was long and difficult, and Romanos did not endear himself to his troops by bringing a luxurious baggage train along with him; the Byzantine population also suffered some plundering by Romanos' Frankish mercenaries, whom he was forced to dismiss. The expedition first rested at Sebasteia on the Halys, and reached Theodosiopolis in June 1071. There, some of his generals suggested continuing the march into Seljuk territory and catching Arslan before he was ready. Some of the other generals, including Nikephoros Bryennios, suggested they wait there and fortify their position. Eventually it was decided to continue the march.

Thinking that Alp Arslan was either further away or not coming at all, Romanos marched towards Lake Van expecting to retake Manzikert rather quickly, as well as the nearby fortress of Khliat if possible. However, Arslan was actually in Armenia, with 30,000 cavalry from Aleppo, Mosul, and his other allies. Arslan's spies knew exactly where Romanus was, while Romanos was completely unaware of his opponent's movements.

Romanos ordered his general Joseph Tarchaneiotes to take some of the Byzantine troops and Varangians and accompany the Pechenegs and Franks to Khliat, while Romanos and the rest of the army marched to Manzikert. This split the forces in half, each taking about 30,000 men.[10] It is unknown what happened to the army sent off with Joseph Tarchaneiotes - according to Islamic sources, Alp Arslan smashed his army; however Byzantine sources remain quiet of any such encounter,[10] whilst Attaleiates suggests that Tarchaneiotes fled at the sight of the Seljuk Sultan - an unlikely event considering the reputation of the Byzantine general. Either way, Romanus' army was reduced to less than half his planned 60-70,000.[10]

[edit] The battle

Romanus was unaware of the loss of Tarchaneiotes and continued to Manzikert, even thpugh he was, which he easily captured on August 23. The Seljuks responded with heavy incursions by bowmen The next day some foraging parties under Bryennios discovered the Seljuk force and were forced to retreat back to Manzikert. The Armenian general Basilaces was sent out with some cavalry, as Romanos did not believe this was Arslan's full army; the cavalry was destroyed and Basilaces taken prisoner. Romanos drew up his troops into formation and sent the left wing out under Bryennios, who was almost surrounded by the quickly approaching Turks and was forced to retreat once more. The Turks hid among the nearby hills for the night, making it nearly impossible for Romanus to send a counterattack.

On August 25, some of Romanos' Turkish mercenaries came into contact with their Seljuk relatives and deserted. Romanos then rejected a Seljuk peace embassy[11] as he wanted to settle the Turkish problem with a decisive military victory and understood that raising another army would be both difficult and expensive. The Emperor attempted to recall Tarchaneiotes, who was no longer in the area. There were no engagements that day, but on August 26 the Byzantine army gathered itself into a proper battle formation and began to march on the Turkish positions, with the left wing under Bryennios, the right wing under Theodore Alyates, and the centre under the emperor. Andronikos Doukas led the reserve forces in the rear - a foolish mistake, considering the loyalties of the Dukas. The Seljuks were organized into a crescent formation about four kilometres away,[11] with Arslan observing events from a safe distance. Seljuk archers attacked the Byzantines as they drew closer; the centre of their crescent continually moved backwards while the wings moved to surround the Byzantine troops.

The Byzantines held off the arrow attacks and captured Arslan's camp by the end of the afternoon. However, the right and left wings, where the arrows did most of their damage, almost broke up when individual units tried to force the Seljuks into a pitched battle; the Seljuk cavalry simply fled when challenged, the classic hit and run tactics of steppe warriors. With the Seljuks avoiding battle,[9] Romanos was forced to order a withdrawal by the time night fell.[9] However, the right wing misunderstood the order, and Doukas, as an enemy of Romanos, deliberately ignored the emperor and marched back to the camp outside Manzikert, rather than covering the emperor's retreat. Now that the Byzantines were thoroughly confused, the Seljuks seized the opportunity and attacked.[9] The Byzantine right wing was routed; the left under Bryennios held out a little longer but was soon routed as well.[12] The remnants of the Byzantine centre, including the Emperor and the Varangian Guard, were encircled by the Seljuks. Romanus was injured, and taken prisoner by the Seljuks. The survivors were the many who fled the field and were pursued throughout the night; by dawn, the professional core of the Byzantine army had been destroyed but many of the Peasant troops and levies who had been under the command of Andronikus fled.[12]

[edit] Captivity of Romanus Diogenes

When the Emperor Romanos IV was conducted into the presence of Alp Arslan, he refused to believe that the bloodied and tattered man covered in dirt was the mighty Emperor of the Romans. After discovering the identity of the Emperor, he treated him with considerable kindness, and again offered the terms of peace which he had offered previous to the battle - all of course, after the Seljuk Sultan had forced his neck to the ground, placed his boot upon it and made Romanus kiss the ground before him.[12] He was also loaded with presents and Alp Arslan had him respectfully escorted by a military guard to his own forces. But prior to that, when he first was brought to the Sultan, this famous conversation is reported to have taken place:

- Alp Arslan: "What would you do if I were brought before you as a prisoner?"

- Romanus: "Perhaps I'd kill you, or exhibit you in the streets of Constantinople."

- Alp Arslan: "My punishment is far heavier. I forgive you, and set you free."

Romanus remained a captive of the Sultan for a week. During this time, the Sultan allowed Romanus to eat at his table whilst concessions were agreed upon; Antioch, Edessa, Hieropolis and Manzikert were to be surrendered.[13] A payment of 10 million golden pieces as a ransom was deemed as too high by Romanus so the Sultan reduced its short-term expense by instead asking for 1.5 million as an initial payment followed by an annual sum of 360,000 pieces of gold.[13] Finally, Romanus would marry one of his daughters to the Sultan. The Sultan then gave Romanus and escort of two emirs and a hundred Mamelukes to Constantinople. Shortly after his return to his subjects, Romanos found his rule in serious trouble. Despite attempts to raise loyal troops, he was defeated three times in battle against the Doukas family and was deposed, blinded and exiled to the island of Proti; soon after, he died as a result of an infection caused by an injury during his brutal blinding. Romanus' last events in the Anatolian heartland that he worked so hard to defend was a public humiliation on a donkey with a rotten face.[13]

[edit] Aftermath

Despite being a complete tactical disaster and a long-term strategic catastrophe for Byzantium, Manzikert was by no means the massacre that earlier historians presumed. Modern scholars estimate that Byzantine losses were relatively low, considering that many units survived the battle intact and were fighting elsewhere within a few months. Certainly, all the commanders in the Byzantine side (Doukas, Tarchaneiotes, Bryennios, de Bailleul, and, above all, the Emperor) survived and took part in later events.

Doukas had escaped with no casualties, and quickly marched back to Constantinople where he led the coup against Romanos. Bryennios also lost few men in the rout of his wing. The Seljuks did not pursue the fleeing Byzantines, nor did they recapture Manzikert itself at this point. The Byzantine army regrouped and marched to Dokeia, where they were joined by Romanos when he was released a week later. The most serious loss materially seems to have been the emperor's extravagant baggage train.

The disaster the battle caused for the Empire was, in simplest terms, the loss of its Anatolian heartland. John Julius Norwich says in his trilogy on the Byzantine Empire that the defeat was "its death blow, though centuries remained before the remnant fell. The themes in Anatolia were literally the heart of the empire, and within decades after Manzikert, they were gone." Or, as Anna Komnene puts it a few decades after the actual battle,

...the fortunes of the Roman Empire had sunk to their lowest ebb. For the armies of the East were dispersed in all directions, because the Turks had over-spread, and gained command of, countries between the Euxine Sea [Black Sea] and the Hellespont, and the Aegean Sea and Syrian Seas [Mediterranean Sea], and the various bays, especially those which wash Pamphylia, Cilicia, and empty themselves into the Egyptian Sea [Mediterranean Sea].[5]

Years and decades later, Manzikert came to be seen as a disaster for the Empire; later sources therefore greatly exaggerate the numbers of troops and the number of casualties. Byzantine historians would often look back and lament the "disaster" of that day, pinpointing it as the moment the decline of the Empire began. It was not an immediate disaster, but the defeat showed the Seljuks that the Byzantines were not invincible — they were not the unconquerable, millennium-old Roman Empire (as both the Byzantines and Seljuks still called it). The usurpation of Andronikos Doukas also politically destabilized the empire and it was difficult to organize resistance to the Turkish migrations that followed the battle. Within a decade almost all of Asia Minor was overrun. Finally, while intrigue and deposing of Emperors had taken place before, the fate of Romanos was particularly horrific, and the destabilization caused by it also rippled through the centuries.

What followed the battle was a chain of events - of which the battle was the first link - that undermined the Empire in the years to come. They included intrigues for the throne, the horrific fate of Romanos and Roussel de Bailleul attempting to carve himself an independent kingdom in Galatia with his 3,000 Frankish, Norman and German mercenaries. He defeated the Emperor's uncle John Doukas who had come to suppress him, advancing toward the capital to destroy Chrysopolis (Üsküdar) on the Asian coast of the Bosphorus. The Empire finally turned to the spreading Seljuks to crush de Bailleul (which they did, then delivering him over). These events all interacted to create a vacuum that the Turks filled. Their choice in establishing their capital in Nikaea (İznik) in 1077 could possibly be explained by a desire to see if the Empire's struggles could present new opportunities.

In hindsight, both Byzantine and contemporary historians are unanimous in dating the decline of Byzantine fortunes to this battle. It is interpreted as one of the root causes for the later Crusades, in that the First Crusade of 1095 was originally a western response to the Byzantine emperor's call for military assistance after the loss of Anatolia. From another perspective, the West saw Manzikert as a signal that Byzantium was no longer capable of being the protector of Eastern Christianity or Christian pilgrims to the Holy Places in the Middle East.

Delbruck considers that the importance of the battle has been exaggerated; but it is clear from the evidence that as a result of it, the Empire was unable to put an effective army into the field for many years to come.

The Battle of Myriokephalon, also known as the Myriocephalum, was 'also' compared to the Battle of Manikert, as a 'pivotal' point in the "decline' of the Byzantine Empire.

[edit] Notes

- ^ Konstam, Angus (2004). The Crusades. London: Mercury Books, p. 40.

- ^ Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage Books, p. 238.

- ^ David Eggenberger, An Encyclopedia of Battles, Dover Publications, 1985.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: a historical atlas. The University of Chicago Press, p. 126. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- ^ Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann Katharine Swynford Lambton, Bernard Lewis The Cambridge History of Islam, 1977, p.231,232 [1]

- ^ a b Konstam, Angus (2004). The Crusades. London: Mercury Books, p. 40.

- ^ Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage Books, p. 236.

- ^ Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage Books, p. 237. - "The fate of Caesarea was well known"

- ^ a b c d Grant, R.G. (2005). Battle a Visual Journey Through 5000 Years of Combat. London: Dorling Kindersley, p. 77.

- ^ a b c d Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage Books, p. 298.

- ^ a b Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage Books, p. 239.

- ^ a b c Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage Books, p. 240.

- ^ a b c Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage Books, p. 241.

[edit] References

- Haldon, John. The Byzantine Wars: Battles and Campaigns of the Byzantine Era, 2001. ISBN 0-7524-1795-9.

- Treadgold, Warren. A History of the Byzantine State and Society, Stanford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8047-2421-0.

- Runciman, Sir Steven. A History of the Crusades (Volume One), Harper & Row, 1951.

- Norwich, John Julius. Byzantium: The Apogee, Viking, 1991. ISBN 0-670-80252-2.

- Carey, Brian Todd; Allfree, Joshua B.; Cairns, John. Warfare in the Medieval World, Pen & Sword Books ltd, 2006. ISBN 1-84415-339-8

- Konstam, Angus. Historical Atlas of The Crusades

[edit] External links

- Battle of Manzikert: Military Disaster or Political Failure? By Paul Markham

- Debacle at Manzikert, 1071: Prelude to the Crusades, by Brian T. Carey (Issue 5 - January 2004)

- Log in to post comments

1073AD Hildebrand becomes Pope Gregory VII

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pope_Gregory_VII

Pope Gregory VII

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Gregory VII | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Hildebrand Bonizi |

| Papacy began | April 22, 1073 |

| Papacy ended | May 25, 1085 |

| Predecessor | Alexander II |

| Successor | Victor III |

| Born | c. 1020 Sovana, Italy |

| Died | May 25, 1085 Salerno, Italy |

| Other popes named Gregory | |

| Styles of Pope Gregory VII | |

|---|---|

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | Saint |

Pope Saint Gregory VII (c. 1020/1025 – May 25, 1085), born Hildebrand of Soana (Italian: Ildebrando di Soana), was pope from April 22, 1073, until his death. One of the great reforming popes, he is perhaps best known for the part he played in the Investiture Controversy, which pitted him against Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV. He was beatified by Gregory XIII in 1584, and canonized in 1728 by Benedict XIII.[1]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Biography

[edit] Early years

Hildebrand was born in Soana (modern Sovana), a small town in southern Tuscany. He belonged to the noble Aldobrandeschi family.

He was sent to Rome, where his uncle was abbot of the monastery of St. Mary on the Aventine hill, and his experience in the city was a formative influence on his character. Pope Gregory VI may have been among his instructors.

When Emperor Henry III deposed Gregory VI, Hildebrand followed him in exile to Germany. Though he initially had no desire to cross the Alps, his residence in Germany was of great educational value and significant in his later life. He pursued his studies in Cologne before eventually returning to Rome with Pope Leo IX. Under his guidance, Hildebrand first began work in the ecclesiastical service and became a subdeacon and steward in the Roman Catholic Church.

Upon the death of Leo IX, Hildebrand was sent as a Roman envoy to the German court to conduct negotiations regarding Leo's successor. Hildebrand encouraged the Emperor to support Gebhard of Calw, who, as Pope Victor II (served as the Pope from 1055-1057), employed Hildebrand as his legate to France. In France, Hildebrand addressed the question of Berengar of Tours, whose views on the Eucharist had caused controversy. When Pope Stephen IX was elected in 1057 without previous consultation with the German court, Hildebrand and Bishop Anselm of Lucca were sent to Germany to secure a belated recognition and succeeded in gaining the consent of the empress, Agnes de Poitou. Stephen, however, died early the next year, before Hildebrand's return to France.

In a desperate effort to recover their influence on the papal throne, the Roman aristocracy managed the hasty elevation of Bishop Johannes of Velletri as Pope Benedict X in 1058. This course of action was dangerous to the Church as it implied a renewal of the disastrous patrician régime; that the crisis was overcome was essentially the work of Hildebrand. With Hildebrand's support, Benedict was supplanted by Pope Nicholas II in 1059, a leader who strongly influenced the policy of the Curia during the next two decades, including the rapprochement with the Normans in the south of Italy and the alliance with the democratic and, subsequently, anti-German movement of the Patarenes in the north.

It was also under this pontificate that the law was enacted transferring the papal election to the College of Cardinals, thus withdrawing it from the nobility of Rome and diminishing German influence on the election. When Nicholas II died and was succeeded by Pope Alexander II in 1061, Hildebrand loomed larger in the eyes of his contemporaries as the soul of Curial policy, as the Archdeacon in charge of the routine administration of the Roman see during Alexander's frequent absences in Lucca, where he retained his see. The general political conditions, especially in Germany, were at that time very favorable to the Curia, but to use them with the wisdom actually shown was nevertheless a great achievement, and the position of Alexander at the end of his pontificate in 1073 was a brilliant justification of Hildebrandine statecraft.

[edit] Election to the Papacy

On the death of Alexander II (April 21, 1073), as the obsequies were being performed in the Lateran basilica, there arose a loud outcry from the whole multitude of clergy and people: "Let Hildebrand be pope!" "Blessed Peter has chosen Hildebrand the Archdeacon!" All remonstrances on the part of the archdeacon were vain, his protestations fruitless. Later, on the same day, Hildebrand was conducted to the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, and there elected in legal form by the assembled cardinals, with the due consent of the Roman clergy and amid the repeated acclamations of the people. That this extraordinary outburst on the part of the clergy and people in favour of Hildebrand could have been the result of some preconcerted arrangements, as is sometimes alleged, does not appear likely. Hildebrand became pope and took the name of Gregory VII. The mode of his election was highly criticized by his opponents. Many of the charges brought may have been expressions of personal dislike, liable to suspicion from the very fact that they were not raised to attack his promotion until several years later; but it is clear from his own account of the circumstances of his election that it was conducted in a very irregular fashion, and that the forms prescribed by the law of 1059 were not observed, namely, the command of Nicholas II that the German emperor be consulted in the matter. However, what ultimately turned the tide in favor of validity of Gregory's election was the fact that near universal acclaim of the populus Romanus was undeniable. In this sense, his election hearkened back to the earliest centuries of the Church of Rome, regardless of later canonical legislation. Gregory's earliest pontifical letters clearly acknowledge this fact, and thus helped defuse any doubt about his election as immensely popular. On May 22 he received sacerdotal ordination, and on June 30 episcopal consecration.

In the decree of election those who had chosen him as pontiff proclaimed him "a devout man, a man mighty in human and divine knowledge, a distinguished lover of equity and justice, a man firm in adversity and temperate in prosperity, a man, according to the saying of the Apostle, of good behaviour, blameless, modest, sober, chaste, given to hospitality, and one that ruleth well his own house; a man from his childhood generously brought up in the bosom of this Mother Church, and for the merit of his life already raised to the archidiaconal dignity". "We choose then", they said to the people, "our Archdeacon Hildebrand to be pope and successor to the Apostle, and to bear henceforward and forever the name of Gregory" (April 22, 1073).[2]

The focus of the ecclesiastico-political projects of Gregory VII is to be found in his relationship with Germany. Since the death of Henry III the strength of the German monarchy had been seriously weakened, and his son Henry IV had to contend with great internal difficulties. This state of affairs was of material assistance to the pope. His advantage was still further accentuated by the fact that in 1073 Henry was only twenty-three and inexperienced.

In the two following years Henry was forced by the Saxon rebellion to come to amicable terms with the pope at any cost. Consequently in May 1074 he did penance at Nuremberg in the presence of the papal legates to atone for his continued friendship with the members of his council who had been banned by Gregory, took an oath of obedience, and promised his support in the work of reforming the Church. This attitude, however, which at first won him the confidence of the pope, was abandoned as soon as he defeated the Saxons by his victory at the Battle of Hohenburg (June 9, 1075). He now tried to reassert his rights as the sovereign of northern Italy without delay.

He sent Count Eberhard to Lombardy to combat the Patarenes; nominated the cleric Tedaldo to the archbishopric of Milan, thus settling a prolonged and contentious question; and finally tried to establish relations with the Norman duke, Robert Guiscard. Gregory VII replied with a rough letter, dated December 8, in which, among other charges, he accused the German king of breaching his word and with his continued support of the excommunicated councillors; while at the same time he sent a verbal message suggesting that the enormous crimes which would be laid to his account rendered him liable, not only to the ban of the church, but to the deprivation of his crown. Gregory did this at a time when he himself was confronted by a reckless opponent in the person of Cencio I Frangipane, who on Christmas-night surprised him in church and carried him off as a prisoner, though on the following day Gregory was released.

[edit] Conflict with the Emperor

The reprimands of the pope, couched as they were in such an unprecedented form, infuriated Henry and his court, and their answer was the hastily convened national council in Worms, Germany (synod of Worms), which met on January 24, 1076. In the higher ranks of the German clergy Gregory had many enemies, and a Roman cardinal, Hugo Candidus, once on intimate terms with him but now his opponent, had hurried to Germany for the occasion and appeared at Worms. All the accusations with regard to the pope that Candidus could come up with were well received by the assembly, which committed itself to the resolution that Gregory had forfeited the papacy. In one document full of accusations, the bishops renounced their allegiance. In another King Henry pronounced him deposed, and the Romans were required to choose a new pope [1]. The council sent two bishops to Italy, and they procured a similar act of deposition from the Lombard bishops in the synod of Piacenza. Roland of Parma informed the pope of these decisions, and he was fortunate enough to gain an opportunity for speech in the synod, which had just assembled in the Lateran church, and he delivered his message there announcing the dethronement. For the moment the members were frightened, but soon such a storm of indignation was aroused that it was only

On the following day the pope pronounced the sentence of excommunication against the German king Henry IV with all due solemnity, divested him of his royal dignity and absolved his subjects from the oaths they had sworn to him. This sentence purported to eject the king from the church and to strip him of his crown. Whether it would produce this effect, or whether it would remain an idle threat, depended not so much on Gregory as on Henry's subjects, and, above all, on the German princes. Contemporary evidence suggests that the excommunication of the king made a profound impression both in Germany and Italy. Thirty years before, Henry III had deposed three popes, and thereby rendered an acknowledged service to the church. When Henry IV tried to copy this procedure he was less successful, as he lacked the support of the people. In Germany there was a rapid and general revulsion of feeling in favour of Gregory, and the princes took the opportunity to carry out their anti-regal policy under the cloak of respect for the papal decision. When at Whitsun the king proposed to discuss the measures to be taken against Gregory in a council of his nobles, only a few made their appearance; the Saxons snatched at the golden opportunity for renewing their rebellion, and the anti-royalist party grew in strength from month to month.

[edit] To Canswayla

The situation now became extremely critical for Henry. As a result of the agitation, which was zealously fostered by the papal legate Bishop Altmann of Passau, the princes met in October at Trebur to elect a new German king, and Henry, who was stationed at Oppenheim on the left bank of the Rhine, was only saved from the loss of his throne by the failure of the assembled princes to agree on the question of his successor. Their dissension, however, merely induced them to postpone the verdict. Henry, they declared, must make reparation to the pope and pledge himself to obedience; and they decided that, if, on the anniversary of his excommunication, he still lay under the ban, the throne should be considered vacant. At the same time they decided to invite Gregory to Augsburg to decide the conflict. These arrangements showed Henry the course to be pursued. It was imperative, under any circumstances and at any price, to secure his absolution from Gregory before the period named, otherwise he could scarcely foil his opponents in their intention to pursue their attack against him and justify their measures by an appeal to his excommunication. At first he attempted to attain his ends by an embassy, but when Gregory rejected his overtures he took the celebrated step of going to Italy in person.

The pope had already left Rome, and had intimated to the German princes that he would expect their escort for his journey on January 8 in Mantua. But this escort had not appeared when he received the news of the king's arrival. Henry, who had traveled through Burgundy, had been greeted with enthusiasm by the Lombards, but resisted the temptation to employ force against Gregory. He chose instead the unexpected course of forcing the pope to grant him absolution by doing penance before him at Canossa, where he had taken refuge. This event soon became legendary. The reconciliation was only effected after prolonged negotiations and definite pledges on the part of the king, and it was with reluctance that Gregory at length gave way, for, if he gave his absolution, the diet of princes in Augsburg, in which he might reasonably hope to act as arbitrator, would either become useless, or, if it met at all, would change completely in character. It was impossible, however, to deny the penitent re-entrance into the church, and his religious obligations overrode his political interests.

The removal of the ban did not imply a genuine reconciliation, and no basis was gained for a settlement of the great questions at issue: notably that of investiture. A new conflict was inevitable from the very fact that Henry IV naturally considered the sentence of deposition repealed along with that of excommunication; while Gregory on the other hand was intent on reserving his freedom of action and gave no hint on the subject at Canossa.

[edit] Second excommunication of Henry

That the excommunication of Henry IV was simply a pretext, not a motive, for the opposition of the rebellious German nobles is transparent. Not only did they persist in their policy after his absolution, but they took the more decided step of setting up a rival king in the person of Duke Rudolph of Swabia (Forchheim, March 1077). At the election the papal legates present observed the appearance of neutrality, and Gregory himself sought to maintain this attitude during the following years. His task was made easier in that the two parties were of fairly equal strength, each trying to gain the upper hand by getting the pope on their side. But the result of his non-committal policy was that he largely lost the confidence of both parties. Finally he decided for Rudolph of Swabia after his victory at Flarchheim (January 27, 1080). Under pressure from the Saxons, and misinformed as to the significance of this battle, Gregory abandoned his waiting policy and again pronounced the excommunication and deposition of King Henry (March 7, 1080).

But the papal censure now proved a very different thing from the papal censure four years before. It was widely felt to be an injustice, and people began to ask whether an excommunication pronounced on frivolous grounds was entitled to respect. To make matters worse, Rudolph of Swabia died on October 16 of the same year. A new claimant, Hermann of Luxembourg, was put forward in August 1081, but his personality was not suitable for a leader of the Gregorian party in Germany, and the power of Henry IV was at its peak. The king, now more experienced, took up the struggle with great vigour. He refused to acknowledge the ban on the ground of its illegality. A council had been summoned at Brixen, and on June 16 it pronounced Gregory deposed and nominated the archbishop Guibert of Ravenna as his successor. In 1081 Henry opened the conflict against Gregory in Italy. The latter had now become less powerful, and thirteen cardinals deserted him. Rome surrendered to the German king in 1084, and Gregory thereupon retired into the exile of Sant' Angelo, and refused to entertain Henry's overtures, although the latter promised to hand over Guibert as a prisoner, if the sovereign pontiff would only consent to crown him emperor. Gregory, however, insisted as a necessary preliminary that Henry should appear before a council and do penance. The emperor, while pretending to submit to these terms, tried hard to prevent the meeting of the bishops. A small number however assembled, and, in accordance with their wishes, Gregory again excommunicated Henry. Henry upon receipt of this news again entered Rome on March 21 to see that Guibert of Ravenna be enthroned as Clement III (March 24, 1084). Henry was crowned emperor by his creature, but Robert Guiscard, Duke of Normandy, with whom Gregory had formed an alliance, was already marching on the city, and Henry fled towards Citta Castellana. The pope was liberated, but, the people becoming incensed by the excesses of his Norman allies, he was compelled to withdraw to Monte Cassino, and later to the castle of Salerno by the sea, where he died in the following year. Three days before his death he withdrew all the censures of excommunication that he had pronounced, except those against the two chief offenders—Henry and Guibert.

[edit] Papal policy to the rest of Europe

The relationship of Gregory to other European states was strongly influenced by his German policy; as Germany, by taking up most of his powers, often forced him to show to other rulers the very moderation which he withheld from the German king. The attitude of the Normans brought him a rude awakening. The great concessions made to them under Nicholas II were not only powerless to stem their advance into central Italy but failed to secure even the expected protection for the papacy. When Gregory was hard pressed by Henry IV, Robert Guiscard left him to his fate, and only intervened when he himself was threatened with German arms. Then, on the capture of Rome, he abandoned the city to his troops, and the popular indignation evoked by his act brought about Gregory's exile.

In the case of several countries, Gregory tried to establish a claim of sovereignty on the part of the Papacy, and to secure the recognition of its self-asserted rights of possession. On the ground of "immemorial usage"; Corsica and Sardinia were assumed to belong to the Roman Church. Spain and Hungary were also claimed as her property, and an attempt was made to induce the king of Denmark to hold his realm as a fief from the pope. Philip I of France, by his practice of simony and the violence of his proceedings against the Church, provoked a threat of summary measures; and excommunication, deposition and the interdict appeared to be imminent in 1074. Gregory, however, refrained from translating his threats into actions, although the attitude of the king showed no change, for he wished to avoid a dispersion of his strength in the conflict soon to break out in Germany. In England, William the Conqueror also derived benefits from this state of affairs. He felt himself so safe that he interfered autocratically with the management of the church, forbade the bishops to visit Rome, made appointments to bishoprics and abbeys, and showed little anxiety when the pope lectured him on the different principles which he had as to the relationship of spiritual and temporal powers, or when he prohibited him from commerce or commanded him to acknowledge himself a vassal of the apostolic chair. Gregory had no power to compel the English king to an alteration in his ecclesiastical policy, so he chose to ignore what he could not approve, and even considered it advisable to assure him of his particular affection.

Gregory, in fact, established some sort of relations with every country in Christendom; though these relations did not invariably realize the ecclesiastico-political hopes connected with them. His correspondence extended to Poland, Russia and Bohemia. He wrote in friendly terms to the Saracen king of Mauretania in north Africa, and unsuccessfully tried to bring Armenia into closer contact with Rome. He was particularly concerned with the East. The schism between Rome and the Byzantine Empire was a severe blow to him, and he worked hard to restore the former amicable relationship. Gregory successfully tried to get in touch with the emperor Michael VII. When the news of the Arab attacks on the Christians in the East filtered through to Rome, and the political embarrassments of the Byzantine emperor increased, he conceived the project of a great military expedition and exhorted the faithful to participate in recovering the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. In his treatment of ecclesiastical policy and ecclesiastical reform, Gregory did not stand alone, but found powerful support: in England Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury stood closest to him; in France his champion was Bishop Hugo of Dié, who afterwards became Archbishop of Lyon.

[edit] Internal policy and reforms

- .

His life-work was based on his conviction that the Church was founded by God and entrusted with the task of embracing all mankind in a single society in which divine will is the only law; that, in her capacity as a divine institution, she is supreme over all human structures, especially the secular state; and that the pope, in his role as head of the Church, is the vice-regent of God on earth, so that disobedience to him implies disobedience to God: or, in other words, a defection from Christianity. But any attempt to interpret this in terms of action would have bound the Church to annihilate not merely a single state, but all states. Thus Gregory, as a politician wanting to achieve some result, was driven in practice to adopt a different standpoint. He acknowledged the existence of the state as a dispensation of Providence, described the coexistence of church and state as a divine ordinance, and emphasized the necessity of union between the sacerdotium and the imperium. But at no period would he have dreamed of putting the two powers on an equal footing; the superiority of church to state was to him a fact which admitted of no discussion and which he had never doubted.

He wished to see all important matters of dispute referred to Rome; appeals were to be addressed to himself; the centralization of ecclesiastical government in Rome naturally involved a curtailment of the powers of bishops. Since these refused to submit voluntarily and tried to assert their traditional independence, his papacy is full of struggles against the higher ranks of the clergy.

This battle for the foundation of papal supremacy is connected with his championship of compulsory celibacy among the clergy and his attack on simony. Gregory VII did not introduce the celibacy of the priesthood into the Church, but he took up the struggle with greater energy than his predecessors. In 1074 he published an encyclical, absolving the people from their obedience to bishops who allowed married priests. The next year he enjoined them to take action against married priests, and deprived these clerics of their revenues. Both the campaign against priestly marriage and that against simony provoked widespread resistance.

His writings treat mainly of the principles and practice of Church government. They may be found under the title "Gregorii VII registri sive epistolarum libri"[3].

[edit] Death

He died an exile in Salerno; his last words were: Amavi iustiam et odivi iniquitatem; propterea, morior in exilio [I have loved justice and hated iniquity; therefore, I die in exile]. The Romans and a number of his most trusted helpers had renounced him, and the faithful band in Germany had shrunk to small numbers. Curiously for more than 900 years, the people of Salerno have zealously guarded Gregory's mortal remains and refused to permit him to be taken back for burial in St. Peter's, the traditional resting place of an overwhelming number of popes. Today, his beautiful sarcophagus lies in perpetual testament to his struggles and sanctify in the cathedral church of Salerno, Italy.

[edit] References

- ^

Thomas Oestreich (1913). "|Pope St. Gregory VII]". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

Thomas Oestreich (1913). "|Pope St. Gregory VII]". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved on 2007-12-10. - ^ Mansi, "Conciliorum Collectio", XX, 60.

- ^ Mansi, "Gregorii VII registri sive epistolarum libri." Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio. Florence, 1759

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- This article incorporates text from the public-domain Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913.

[edit] Further reading

- Cowdrey, H.E.J. (1998). Pope Gregory VII: 1073–1085. Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press.

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alexander II | Pope 1073–1085 | Succeeded by Victor III |

| [show] Popes of the Catholic Church (chronologically) |

|---|

- Log in to post comments

The Crusades - a synopsis

From: http://www.equip.org/articles/hollywood-vs-history?msource=EC110225WKLY&tr=y&auid=7827902

Hollywood vs. History