69AD Otho: 9TH ROMAN "KING" since Rome possessed Jerusalem but never possessed her himself, Jerusalem enjoying freedom through revolt

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otho

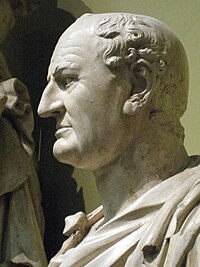

Otho

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Otho (disambiguation).

| Otho | |

|---|---|

| Emperor of the Roman Empire | |

| |

| Denarius of Otho | |

| Reign | 15 January 69 – 16 April 69 |

| Full name | Marcus Salvius Otho |

| Born | 25 April 32 |

| Ferentium | |

| Died | 16 April 69 (aged 36) |

| Rome | |

| Predecessor | Galba |

| Successor | Vitellius |

| Wife/wives | Poppea Sabina (forced to divorce her by Nero) |

| Dynasty | None |

| Father | Lucius Otho |

| Mother | Terentia Albia |

Marcus Salvius Otho (April 25, 32 – April 16, 69), also called Marcus Salvius Otho Nero, was Roman Emperor from January 15 to April 16, in 69, the second emperor of the Year of the four emperors.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Birth and lineage

Otho belonged to an ancient and noble Etruscan family, descended from the princes of Etruria and settled at Ferentinum (modern Ferento, near Viterbo) in Etruria. His paternal grandfather Marcus Salvius Otho, whose father was a Roman knight but whose mother was of lowly origin and perhaps not even free-born, was raised in Livia's household and rose to senatorial rank through her influence, although he did not advance beyond the rank of praetor. His father was Lucius Otho.

[edit] Early life

The future emperor appears first as one of the most reckless and extravagant of the young nobles who surrounded Nero. This friendship was brought to an end in 58 because of a woman, Poppea Sabina. Otho introduced his beautiful wife to the Emperor upon the insistence of his wife, who then began an affair that would eventually be the death of her. After securely establishing this position as his mistress, she divorced Otho and had the emperor send him away to the remote province of Lusitania (modern Portugal and Extremadura).

Otho remained in Lusitania for the next ten years, administrating the province with a moderation unusual at the time. When in 68 his neighbor Galba, the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, rose in revolt against Nero, Otho accompanied him to Rome. Resentment at the treatment he had received from Nero may have impelled him to this course, but to this motive was added before long that of personal ambition. Galba was childless and far advanced in years, and Otho, encouraged by the predictions of astrologers, aspired to succeed him. He came to a secret agreement with Galba's favourite, Titus Vinius, agreeing to marry Vinius' daughter in exchange for his support. However in January 69 his hopes were dissipated by Galba's formal adoption of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Licinianus, whom Galba had previously named a recipient in his will.

Nothing remained for Otho but to strike a bold blow. Desperate as was the state of his finances, thanks to his previous extravagance, he found money to purchase the services of some twenty-three soldiers of the Praetorian Guard. On the morning of January 15, only five days after the adoption of Piso, Otho attended as usual to pay his respects to the emperor, and then hastily excusing himself on the score of private business hurried from the Palatine to meet his accomplices. He was then escorted to the Praetorian camp, where, after a few moments of surprise and indecision, he was saluted imperator.

With an imposing force he returned to the Forum, and at the foot of the Capitol encountered Galba, who, alarmed by vague rumors of treachery, was making his way through a dense crowd of wondering citizens towards the barracks of the guard. The cohort on duty at the Palatine, which had accompanied the emperor, instantly deserted him. Galba, his newly adopted son Piso and others were brutally murdered by the Praetorians. The brief struggle over, Otho returned in triumph to the camp, and on the same day was duly invested by the senators with the name of Augustus, the tribunician power and the other dignities belonging to the principate. Otho had owed his success to the resentment felt by the Pretorian guards and the rest of the army at Galba's refusal to pay the promised gold to the ones who supported his accession to the throne. The population of the city was also unhappy with Galba and cherished the memory of Nero. Otho's first acts as emperor showed that he was not unmindful of the facts.

[edit] Decline and fall

He accepted, or appeared to accept, the cognomen of Nero conferred upon him by the shouts of the populace, whom his comparative youth and the effeminacy of his appearance reminded of their lost favourite. Nero's statues were again set up, his freedmen and household officers reinstalled, and the intended completion of the Golden House announced. At the same time the fears of the more sober and respectable citizens were allayed by Otho's liberal professions of his intention to govern equitably, and by his judicious clemency towards Marius Celsus, consul-designate, a devoted adherent of Galba.

But any further development of Otho's policy was checked once Otho read through Galba's private correspondence and realized the extent of the revolution in Germany, where several legions had declared for Vitellius, the commander of the legions on the lower Rhine, and were already advancing upon Italy. After a vain attempt to conciliate Vitellius by the offer of a share in the empire, Otho, with unexpected vigor, prepared for war. From the remoter provinces, which had acquiesced in his accession, little help was to be expected; but the legions of Dalmatia, Pannonia and Moesia were eager in his cause, the pretorian cohorts were in themselves a formidable force and an efficient fleet gave him the mastery of the Italian seas.

The fleet was at once dispatched to secure Liguria, and on the March 14 Otho, undismayed by omens and prophecies, started northwards at the head of his troops in the hopes of preventing the entry of the Vitellius' troops into Italy. But for this he was too late, and all that could be done was to throw troops into Placentia and hold the line of the Po. Otho's advanced guard successfully defended Placentia against Aulus Caecina Alienus, and compelled that general to fall back on Cremona. But the arrival of Fabius Valens altered the aspect of affairs.

Vitellius' commanders now resolved to bring on a decisive battle, the Battle of Bedriacum, and their designs were assisted by the divided and irresolute counsels which prevailed in Otho's camp. The more experienced officers urged the importance of avoiding a battle, until at least the legions from Dalmatia had arrived. But the rashness of the emperor's brother Titianus and of Proculus, prefect of the pretorian guards, added to Otho's feverish impatience, overruled all opposition, and an immediate advance was decided upon, Otho himself remaining behind with a considerable reserve force at Brixellum, on the southern bank of the Po. When this decision was taken, Otho's army had already crossed the Po and were encamped at Bedriacum (or Betriacum), a small village on the Via Postumia, and on the route by which the legions from Dalmatia would naturally arrive.

Leaving a strong detachment to hold the camp at Bedriacum, the Othonian forces advanced along the Via Postumia in the direction of Cremona. At a short distance from that city they unexpectedly encountered the Vitellian troops. The Othonians, though taken at a disadvantage, fought desperately, but were finally forced to fall back in disorder upon their camp at Bedriacum. There on the next day the victorious Vitellians followed them, but only to come to terms at once with their disheartened enemy, and to be welcomed into the camp as friends.

More unexpected still was the effect produced at Brixellum by the news of the battle. Otho was still in command of a formidable force: the Dalmatian legions had already reached Aquileia and the spirit of his soldiers and their officers was unbroken. But he was resolved to accept the verdict of the battle that his own impatience had hastened. In a dignified speech he bade farewell to those about him declaring "It is far more just to perish one for all, than many for one" (Dio, LXIV.13), and then retiring to rest soundly for some hours. Early in the morning he stabbed himself in the heart with a dagger, which he had concealed under his pillow, and died as his attendants entered the tent. Otho's ashes were placed within a modest monument. He had reigned only three months, but in this short time had shown more wisdom and grace than anyone had expected. His funeral was celebrated at once, as he had wished, and not a few of his soldiers followed their master's example by killing themselves at his pyre. A plain tomb was erected in his honour at Brixellum, with the simple inscription Diis Manibus Marci Othonis.

He was almost thirty-seven at the time of his death, and had reigned just three months. His coinage is thus considered rare.

[edit] Reasons for Suicide

It has been thought that Otho's suicide was committed in order to steer his country from the path to civil war. Just as he had come to power, many Romans learned to respect Otho in his death. Few could believe that a renowned former companion of Nero had chosen such an honored end. The soldiers were so moved and impressed that some even threw themselves on the funeral pyre to die with their emperor.

[edit] References

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

[edit] External links

[edit] Primary sources

- Life of Otho (Suetonius; English translation and Latin original)

- Life of Otho (Plutarch; English translation)

- Cassius Dio, Book 63

- Tacitus, Histories (esp. 1.12, 1.21–90)

[edit] Secondary material

- Biography on De Imperatoribus Romanis

- Otho entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- Otho by Plutarch

| Preceded by Galba | Roman Emperor 69 | Succeeded by Vitellius |

| [show] The Works of Plutarch |

|---|

| [show] Roman emperors |

|---|

| [show] Pax Romana emperors |

|---|